Africa-Press – Botswana. Dr David Magang has had a truly remarkable political and business career in his beloved Botswana. He was a long-serving cabinet minister, and his real estate enterprise makes him one of the most successful indigenous business personalities in Botswana’s history.

After retiring at the turn of the new millennium, he also turned his hand to writing. Although a few Batswana public figures, in the form of politicians, have published their memoirs or other books on their vocations, David Magang has become the most prolific.

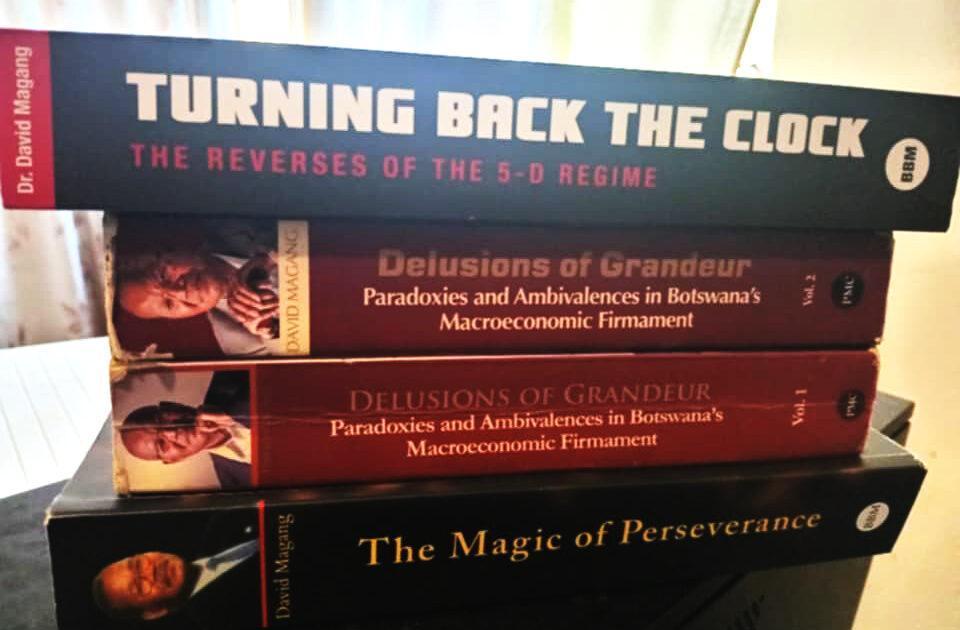

Just like The Magic of Perseverance and Delusions of Grandeur, Turning Back The Clock is also a voluminous magnum opus. It is a treatise on the leadership of former President Lt. Gen. Seretse Khama Ian Khama or Kgosi Khama IV of Bamangwato. He joined politics in 1998 as Vice President to President Festus Mogae, who appointed him. Magang deftly prefaces the Ian Khama story with an insightful account of all Botswana Vice Presidents before him. The reader is offered a rich history lesson in the dynamics leading to the appointment of these Vice Presidents and their role or performance in office. This is quite commendable because in a country that does not quite value its history, save for occasional celebratory events and speeches, the book comes in handy.

Magang’s deep appreciation of Botswana’s history is evident in all his books, with The Magic of Perseverance and volume one of Delusions of Grandeur even delving into the precolonial period. His incisive writings, in addition to his contributions to the governance and economy of Botswana, saw the country’s premier higher institution of learning, the University of Botswana, bestow upon him an Honorary Doctor of Letters (DLitt) in 2022.

Ian Khama has been seen by many as an enigma who defies well-known and sacrosanct official government protocols. His leadership style has been very controversial and polarising at the national level and within the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which ruled Botswana from 1966 to 2024. His upbringing, in which he was insulated from the local community despite being a tribal leader, deprived him of the socio-cultural experience needed to prepare him for leadership, thus resulting in his deculturalisation. His only employment was as a police officer, deputy commander, and then commander of the Botswana Defence Force (BDF). Being in the disciplined forces, where orders are obeyed without question, also had an adverse impact on him. Hence, as a civilian leader and politician, the necessary compromises and horse trading were alien and unacceptable to him. Additionally, having been headhunted into the vice presidency, which he accepted on his own unusual and cumbersome terms, did not help matters. Rules had to be modified to accommodate his personal preferences, even when it was abundantly clear that such development undermined the rule of law and customary practice. The result was a Vice President who appeared to overshadow the President. Moreover, matters were not helped by the fact that the President was Ian Khama’s tribal subject. Therefore, Khama’s public life can be described as having been one of power and privilege over duty. For instance, his robust and sustained campaign to collapse the country’s economy by collaborating with international forces after he fell out with his anointed successor, President Mokgweetsi Masisi in 2018, bears testimony to his character.

However, in Botswana’s presidential system, where the constitution gives the sitting President massive powers which engender an imperial presidency, it did not take long for Khama to engage in fierce skirmishes with colleagues in Cabinet, Parliament, BDP, and the private media, among others. As was becoming custom, he normally triumphed over his adversaries because of the country’s power dynamics. Whereas previous Presidents had been circumspect in exercising their presidential powers, after becoming President in 2008, Khama, who was used to getting his way under almost all circumstances, exerted his powers to the fullest. Although he appeared to be insensitive and ruthless, he was well within his constitutional rights to resort to such ‘extreme’ measures. Nevertheless, he also portrayed himself as a benevolent leader who spent a considerable amount of time attending to the poor and underprivileged.

The consequence of Khama’s approach to governance was a culture of fear entrenched by the intelligence apparatus that seemed to serve his interests. Elite corruption and mismanagement in government became rampant, and so was the erosion of civil liberties, overspending on the military with his family members as the main beneficiaries, the erosion of the traditional culture of consultation, political intolerance, compromised independence of the judiciary, and extra-judicial killings became common to a point where former Presidents Sir Ketumile Masire and Festus Mogae openly criticised his leadership style. Despite his inadequate scruples and Botswana being a very small country, Khama’s ‘Wild West’ approach to governance extended to foreign relations, whereby his grandstanding saw him pick up ill-advised fights with major powers such as the United States and China. His robust and sustained campaign to collapse the country’s economy by collaborating with international forces after he fell out with his anointed successor, President Mokgweetsi Masisi in 2018, whom he sought to dislodge, bears testimony to his propensity for power and control.

In this book, Magang provides a blow-by-blow account of almost every aspect of Khama’s leadership and how it negatively impacted the country’s governance, economic, and political development. He shares his personal experience of how Khama’s undue anger affected his ministerial duties, private business, and political career, as well as that of his first-born son and BDP activist, Lesang. One cannot help but sympathise with the Magangs, especially considering the widely held belief that Khama is a highly vindictive man who rarely relents once he takes a dislike to someone. For instance, when the University of Botswana’s hierarchy agreed to award him an Honorary DLitt and even informed him of the exciting news, interference from the presidency prevented the honour from being bestowed upon him. It was only in 2022, after Khama retired in 2018, that the University finally honoured him with the same doctorate without any hindrance.

The book is a welcome addition to the political literature on Botswana, and it is written in Magang’s characteristic erudite style, with elegant and engaging language. It is highly recommended not only for students of Botswana’s history, politics, and public governance but also for general readers who will find it quite enriching.

Turning Back The Clock will be launched on July 25 at Phakalane Hotel

Editor’s note: This review has been abridged for length

For More News And Analysis About Botswana Follow Africa-Press