Africa-Press – Eritrea. For Tedros Mhretu, a seasoned journalist and scholar, the journey from Sweden back to his homeland, Eritrea, has been marked by a deep commitment to education, cultural preservation, and historical inquiry. After many years in Sweden, where he pursued advanced studies in international relations and journalism at the master’s level and gained extensive experience in various media outlets across Sweden and Germany, Tedros returned to Eritrea in 2017. Driven by a desire to give back to his country, he joined Adi Keih College of Arts and Social Sciences as a lecturer in journalism for a year. He has since produced two meticulously researched books, with the second one soon to have its launch ceremony here in Eritrea.

* * *

Welcome, Tedros. Please introduce yourself to our readers, and tell us about your first book.

Thank you. In 2017, I returned to Eritrea with a clear purpose: to share what I’d learned. I became a lecturer at Adi Keih College, teaching journalism for a full year. Honestly, it was one of the most rewarding chapters of my life. Today, I see many of my former students working at the Ministry of Information in television, radio, and newspapers, and that fills me with pride. It feels like something real, something lasting.

In 2018, I asked myself: What else can I do besides teaching? Where do I go from here? The answer, surprisingly, was always with me. History was always my quiet passion. Even when I worked as a journalist, most of my writing leaned to historical narratives. I read history constantly while studying, while working—always. Especially when freelancing, I found myself writing long articles, most of them rooted in the past.

Then something unexpected happened. While researching at a university in Sweden, I stumbled upon a collection. A name popped up: Johannes Kolmodin, a Swedish scholar who had come to Eritrea in 1908. I’d never heard of him. But as I dug deeper, I found something astonishing.

Kolmodin wasn’t just a visitor; he immersed himself in our culture. He spoke fluent Tigrigna, which meant he could sit and talk with elders, listen to their stories, their traditions, and their oral histories. And he wrote everything down. He wasn’t looking for one specific thing; he documented what he heard: stories, myths, fragments of our collective memory.

After his time in Eritrea, he returned to Sweden and compiled his notes into a book titled Traditions of Hazzega and Tseazzega. That book became his PhD dissertation. He even translated it into French first, which was the academic language at the time, and later into Tigrigna, with detailed commentary and analysis. But life pulled him away. He moved to Istanbul, worked there for 13 years, and never returned to the materials. They were locked away in a university archive, untouched for over a century.

And then I found them. I knew about his books about the traditions of Hazzega and Tseagezza but never thought it would have such an extended and detailed material within it. It was accidental; I didn’t know they were there. I spent so much time in those archives, searching and researching, and one day, there they were: manuscripts, piles of them. When they brought them out, I was speechless. I realized I was holding stories that hadn’t been seen or read in 103 years. That’s when I knew I had to do something. I spent two years studying the material, slowly and carefully. Finally, I published a book based on Kolmodin’s research, giving voice to a past that was nearly lost, bringing it back into light. To me, this work is more than academic; it’s personal. It’s cultural. It’s about preservation. It’s about honoring the people who came before us and making sure their voices continue to be heard.

That’s an incredible discovery. What is your second book about?

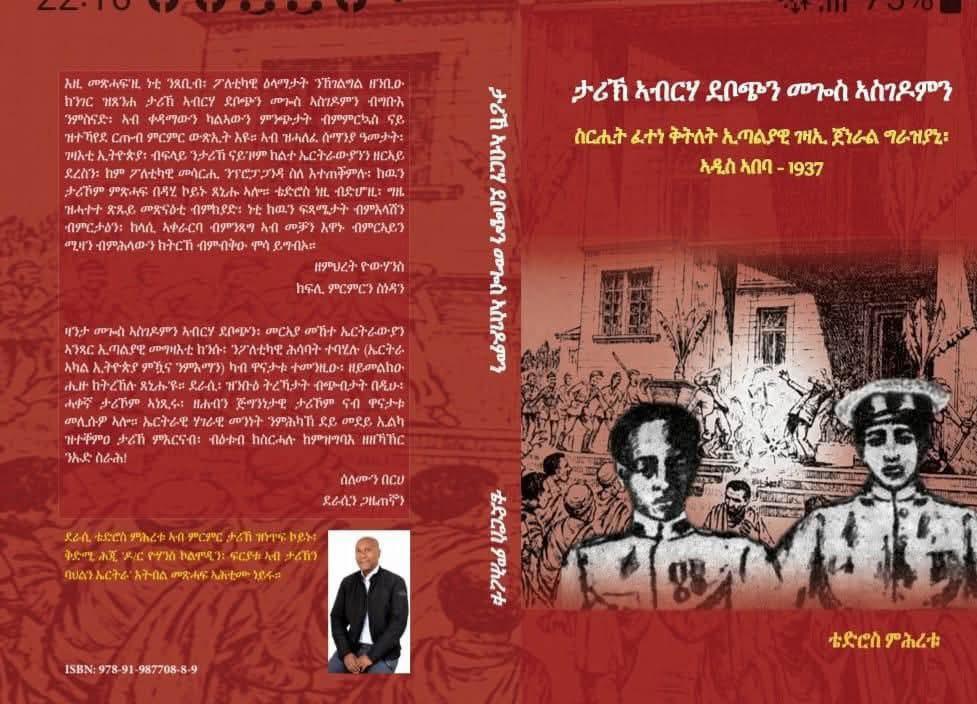

Three years after I published my first book, I wasn’t done. The research opened something in me, and I knew there was more to uncover, more to correct, more to tell. So I turned my focus to two names that have echoed across our region for decades: Abrha Deboch and Mogos Asgedom. Two Eritrean heroes. Two young men—brave, determined, and for far too long, misunderstood.

You see, since 1949, their story has been told through the lens of Ethiopian politics. The Ethiopian state, especially under Haile Selassie, rebranded these two freedom fighters as Ethiopian national heroes. Their names were elevated, yes, but in service of a narrative that wasn’t theirs. It was propaganda. In the late 1940s, Ethiopia was pushing hard to absorb Eritrea, to portray it not as its nation, but as a long-lost province returning “home.” They argued that because the Italians had colonized Eritrea for 60 years, it must have originally belonged to Ethiopia. And to support that claim, they needed heroes. So they reached back and took Abrha and Mogos—two Eritreans who resisted Italian colonialism—and reframed their story. They erased their true identity and motivations and replaced them with a version that served the political goals of unification. They made them Ethiopian. But no one asked: What really happened? Who were these men, truly?

That question drove me. It became the foundation of my second book. I went deep into the archives, reading everything I could find: books, reports, and newspaper articles. I studied the official Ethiopian versions of the story and compared them with lesser-known documents and eyewitness accounts. What I discovered changed everything.

Abrha Deboch and Mogos Asgedom were not Ethiopian agents. They were Eritreans, born and raised. They worked for the Italian administration, yes, but as translators. That position gave them access, and they used it. In February 1937, they carried out a daring attempt in Ethiopia to assassinate the Italian governor in Eritrea, General Graziani. It was a bold act of resistance against colonial rule. Though Graziani survived, badly wounded, the message was clear: Eritreans would not accept foreign rule in silence. After the attempt, Abrha and Mogos tried to flee to Sudan, hoping to regroup and continue their resistance. But they never made it. They were killed in Gondar, a place called Quara, far from home but never far from their purpose.

What they did and why they did it was never about Ethiopia. It was about Eritrea. About freedom. About dignity. And yet, for decades, their story was twisted to serve another agenda. That’s why I wrote this book: to bring their true history to light, to correct the record, and to share new information that has never been published before. Because heroes don’t belong to the loudest voice, they belong to the truth. And now, finally, that truth is being told.

So, your goal with this book is to uncover and correct a truth that had been buried and manipulated for so long?

As a researcher, especially in history, you have to respect the discipline. Every field has its methods, its standards. And I follow those methods with intention and precision. I approach historical research the way historians are trained to: with evidence, structure, and discipline.

But I’m also independent. I’m not tied to any institution or ideology, and that gives me something valuable: freedom—the freedom to think critically, to question deeply, to follow the truth wherever it leads. When I begin a project, I don’t start with assumptions. I don’t begin with a theory I’m trying to prove because once you do that, you’re no longer doing research—you’re doing propaganda. And I refuse to do that.

Instead, I begin with questions. What was happening at the time? Is this account really true? If it’s not, what’s missing? What’s being hidden? How did this event unfold, and who shaped the narrative? These questions bubble up in my mind; they push me, they challenge me. And once they’re there, I know I have to dig. I have to investigate. That’s how every research journey begins for me.

In this kind of work, the questions matter more than anything. If you ask the right questions—honest, sharp, and uncomfortable ones—you have a better chance of finding the truth. That’s the foundation. So no, I don’t come in with a story I want to tell. I let the evidence speak. I let the history unfold. And in doing so, I aim to offer something real, something that helps us understand not just what happened but why it was told the way it was. Because history isn’t just about facts, it’s about who controls the story. And my job as a free thinker and as a disciplined researcher is to make sure that the story is as close to the truth as we can get.

Your second book launch is around the corner. How are you feeling about that?

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been fully immersed in preparing for this moment. It’s been a lot of work behind the scenes, getting everything ready before the official launch. Now, we’re finally reaching the finish line. The preparations are almost complete. And I’m proud to say that my new book will be launched on July 18th. It’s a meaningful moment for me. Not just the end of a long research journey, but the beginning of something new—a chance to share this work with the public, to open up conversations, and to shed light on a history that has been overlooked or misunderstood for far too long. I’m looking forward to the launch and to what comes next.

Would you share some of the challenges you faced while writing your books?

There were a lot of obstacles and challenges in completing this work. As I mentioned earlier, I’ve written and broadcast any journalistic pieces and articles based on my own research, and I’ve also done academic work at the university level. But this recent project was the most difficult task I’ve ever taken on. I knew from the start that it wouldn’t be easy, but even with that in mind, the process was far more challenging than I expected.

This wasn’t just about telling the story of two individuals. Their lives were connected to so many layers of history: British colonialism, Italian occupation, Ethiopian regimes, regional resistance movements, and more. So, before I could even write, I had to understand every one of those layers in depth. It demanded a lot. I struggled. But it was also gratifying; I learned so much in the process. The research itself became an education.

One of the biggest challenges was time, literally. I was researching events that happened over 100 years ago. There’s no one alive today who personally witnessed those moments or knew these two heroes directly. That made it very hard to reconstruct the whole truth. There was one exception that helped me: the British historian Ian Campbell. He did his research in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when some people who had known Abrha Deboch and Mogos Asgedom were still alive. He interviewed them personally. His book provided valuable insight, especially in areas where I had no access to living memory.

Another challenge was language. Researching in Tigrigna is not easy. The structure of the language, the sentence flow, punctuation, and even spelling can vary, and that can make it difficult to maintain clarity and consistency, especially when trying to convey precise historical meaning. But despite all that, I stayed committed because I believe this story matters. And I think that with enough effort, even the most difficult histories can come to light.

As a member of the diaspora who had the opportunity to lecture in one of Eritrea’s colleges and is now on a mission to correct history and claim stolen stories, what advice do you have for others who want to contribute to their homeland? Based on your experience, is there room for making contribution here?

When I first returned to Eritrea in 2017 to teach at the college, I’ll be honest, I didn’t know how the system worked. I had no clear picture. I was stepping into something new and unfamiliar. But to my surprise and my relief, I found something beautiful. The people were incredibly cooperative. From the very beginning, I was met with support and encouragement. The dean of the college, especially, was more than just a colleague; he was a guide. He supported me in every way possible, both professionally and personally. And that kind of support makes all the difference.

What I realized, and what I want to say clearly, is this: If you have something to offer, in any field, you will find people here who are eager to support you. Whether it’s literature, art, science, history, or teaching— whatever your passion is, there is space in this country to make a real impact. That was my experience. I taught at different colleges, and everywhere I went, I found the same spirit: people who were welcoming, students who were curious and grateful, colleagues who encouraged me. They were genuinely happy that I had come from Sweden to teach, and I felt that appreciation every day.

So, to anyone in the diaspora, or anyone thinking about contributing something meaningful to Eritrea: Don’t hesitate. Your knowledge, your skills, your passion—they are needed. And more importantly, they will be welcomed. There is real space here. Space to grow. Space to give. Space to be part of something that matters.

What’s next for Tedros Mhretu?

Right now, I’m fully in this field— the field of research. And I can honestly say I’m happy. Because even though it’s been incredibly challenging, I’ve come through it with something meaningful. After all the struggle, I’ve produced two research-based books. Both were difficult, especially this latest one. But I’m proud because I did it on my own. I’m an independent researcher. I don’t have an institution backing me. No grants. No academic department. Just me, my questions, and my determination to follow the truth wherever it leads. That makes the work harder, but also more honest, more personal.

And I’ve come to realize something: there is still so much history in Eritrea that hasn’t come to light. So many stories that haven’t been told, or have been distorted, or forgotten. I’ve made it my mission to keep digging, to keep researching, to bring those stories forward. So yes, this path is challenging, but I chose it. And I’m staying on it because our history matters. And someone has to tell it.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Tedros Mhretu: There are so many Eritreans who struggled against Italian colonialism, who resisted, who sacrificed, and who stood up for their people. But most of them remain unknown. Forgotten. Erased. And for those few who are known, their stories were often twisted. The Ethiopian regime, for decades, took Eritrean heroes and rewrote their narratives, glorifying them, yes, but for Ethiopia’s political gain. They used those names, those lives, to support their agenda. As a researcher, that has always troubled me. It still does.

That’s why I’ve chosen to continue on this path—to dig deeper into the untold stories of Eritrea. To examine the way history was shaped, distorted, or buried. I want to go back, even as far as 103 years ago, and ask: What happened? Who were these people? And why were their true stories never fully told? This is more than just history for me. It’s a mystery. A responsibility. A calling. I believe these voices deserve to be heard. And I’ll continue to uncover them, one by one. Thank you for blessing me with this opportunity.

Thank you so much for your time. I wish you all the best in your future endeavors.

shabait

For More News And Analysis About Eritrea Follow Africa-Press