By

Rameen Siddiqui

Africa-Press – Eritrea. The 80th session of the United Nations General Assembly commenced this week not with a triumphant fanfare, but with a quiet, procedural hum: a fitting prelude to an institution struggling with its own identity. With UN leadership commemorating eight decades of multilateralism with a gathering on “the path ahead for a more inclusive and responsive multilateral system”, the institution finds itsel mired in a profound crisis of credibility, funding and function.

The new Assembly president, Annalena Baerbock, has promised a new agenda that includes some renewal, but these aspirations clash against a punishing reality: the UN is financially crippled, politically fragmented and struggling to uphold its founding mission in an age of resurgent nationalism. As it turns 80, the gap between its noble ideals and its tangible impact has never been more stark, or more threatening.

At the heart of this anniversary lies Secretary-General António Guterres’s “UN80 Initiative” , a campaign to streamline and refocus the organization. Yet, one must question whether this represents meaningful transformation or merely bureaucratic repackaging. The initiative, while laudable in its intent to modernize, comes out symptomatically UN: a top-down reform initiative that fails to address the root ailment, which is the anachronic and undemocratic power structures entrenched in the Security Council. True “streamlining” cannot occur while the veto power remains a tool for geopolitical deadlock, allowing atrocities to persist unchecked. The initiative risks becoming another chapter in the UN’s long history of prioritizing process over palpable progress, of confusing administrative reshuffling for genuine change.

This structural inertia, exacerbated by a paralyzing financial crisis, largely orchestrated by its most powerful and prolific funder. The United States administration whichp provided some $13 billion in 2023, under the Trump administration has undertaken widespread cuts to foreign aid including capping donations to UN agencies. This fiscal stranglehold has as Richard Gowan of the International Crisis Group observed, placed the UN in a terribly unsound monetary state.

This whipsawing of U.S. policy withdrawing the Paris Accord and the WHO under Trump, then rejoining only to face the threat of another withdrawal shows a devastating vulnerability. The UN’s operational viability is held hostage by the domestic political whims of a single member state, fundamentally undermining its neutrality, its efficacy, and the very principle of collective responsibility it is meant to embody.

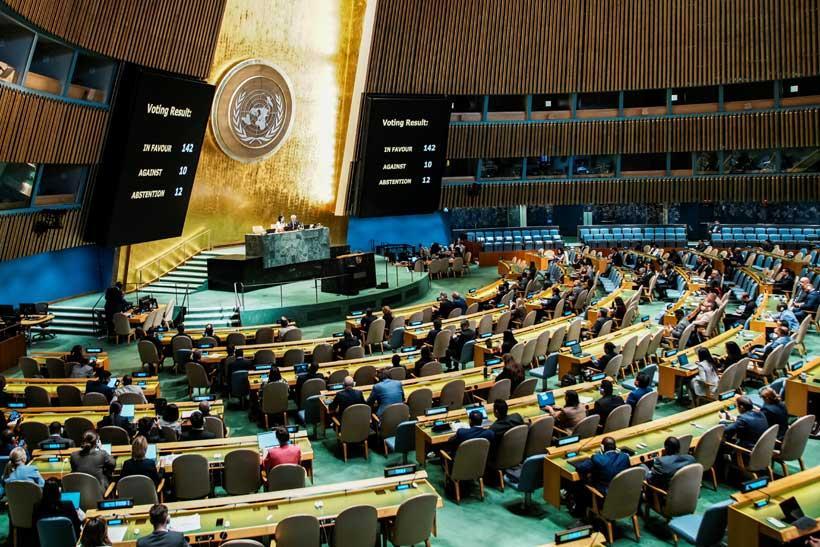

Against this backdrop of internal reform struggles and external financial pressures that the 80th UNGA session unfolds. Procedural formalities of the first week will soon give way to the glittering rhetoric of the high-level week, its sideline diplomacy and array of meetings on development, climate, and health. But one must look past the ceremony. The commemoration of the 80th anniversary,intended to be celebratory, rather reflects the mirror to an institution on the brink.

The theme of inclusivity rings hollow when the organization’s architecture perpetuates a post-World War II power dynamic, marginalizing the Global South. The promise of responsiveness feels empty when the body is often reduced to the stage for performative politics rather than an engine for binding action, developing non-binding resolutions that gather dust as crises gather steam.

Ultimately the 80th session is just a meeting, its metaphor. It represents the enduring hope for global collaboration, but also of bitter recognition of its boundaries. The UN was born from the ashes of a world war with a mandate “to save succeeding generations the scourge of war”. Eighty years on, as wars rage from Gaza to Ukraine, and the climate crises escalate unabated, the mandate remains tragically unfulfilled.

The question is no longer whether the UN needs reform—that is an old and tired refrain. The critical and uncomfortable question we must ask as the speeches reverberate in the General Assembly hall is whether the UN, in its current form, can survive another 80 years without a radical, foundational reckoning. Or will future generations see it as a well intentioned monument to an era of cooperation that never truly was?

moderndiplomacy

For More News And Analysis About Eritrea Follow Africa-Press