Africa-Press – Gambia. Being politically astute and expressive is a daunting task in The Gambia; hence, we struggle to self-manage efficiently, even after 60 years of independence.

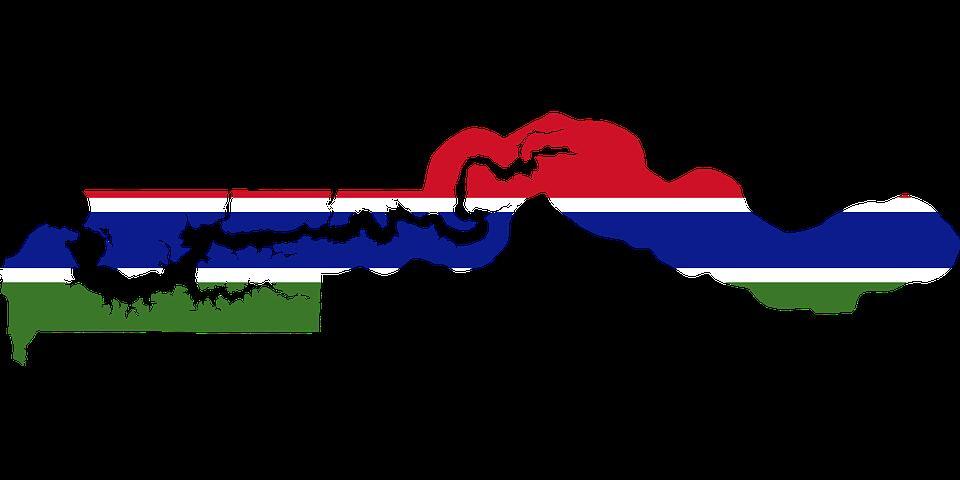

Once upon a very long time ago, over 60 years ago, there was a country called The Gambia, and there still is, the smiling tourist coast of West Africa. Back then, independence was not just a flag or a song; it was a promise whispered along the banks of the River Gambia. Children recited “For the Gambia, our homeland” with pride, and elders dreamt of a nation that would chart its own course. Yet somewhere along that winding river, we lost our way. What has gone abysmally wrong with our country and its people? How did we go from a promising, rising, and enterprising nation to one debt-ridden and suffering a high cost of living?

We no longer look out for each other. Greed, hypocrisy, selfishness and corruption seem to seep into every crack and crevice of society like the rising tide. Our spiritual beliefs and restraints have decayed so severely that many of us are caught up in a new Gambia where few know where we are coming from or where we are heading, how Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara modelled our economy and governance with a touch of colonialism.

Our history would be unremarkable without the late Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara. Sir Dawda, a veterinary surgeon by training and a nation-builder by destiny, helped craft our governance, justice system, education, health, and social welfare. He moulded our finance, economy, agriculture, foreign service, civil service, police and field force, local government, central bank, and Parliament.

These institutions were meant to be the bedrock of our independence, the scaffolding upon which we would build a fair and prosperous state. Under his leadership, there was an emphasis on financial discipline, placing the right people in the right jobs and caring for citizens’ social and emotional welfare. Those early days felt like a seedling pushing through soil.

It was more than a national project; it was part of a regional renaissance. While Sir Dawda and his administration were planning our future, our neighbour Senegal pursued similar political ideologies under the poet president Léopold Sédar Senghor. Across Africa, Jawara and Senghor’s brand of politics, pragmatic yet visionary, became a symbol of envy. Both men were intellectuals who never shied away from the needs of their people. Their characters, calm, measured, and deeply respectful of democratic ideals, set them apart in a continent often beset by coups and strongmen.

The development of our country rested on Sir Dawda’s shoulders; he carried it well, but his ethics and direction were eventually twisted and diluted by a new breed of politicians whose agenda differed vastly from his.

Our concerns:

Today, history appears to repeat itself in our politics. Sir Dawda overstayed his terms but did not do so willingly; he had people behind him who would be exposed without his shield. The inheritors of his legacy veered off course. They became obsessed with wealth, fast cars, and popularity and had little foresight.

We seem to be rehearsing the same political and economic mistakes from the First Republic, lamenting abject poverty and cyclical crises while rarely implementing meaningful solutions. There are many talkers but few doers. Too many politicians inculcate the politics of mischief in their minds. Our so-called political elite and commentators engineer mistrust and bickering, keeping us in perpetual motion but seldom in progress.

The First Republic laid some solid foundations: reasonable financial regulations, sound economic policies, good governance, and strategies for running healthcare, education, and agriculture. A designated youth week and a functional Independence Stadium highlighted youth development and cooperation.

Our education pioneers: the late Charles Chow, the late Kama Badjie, Mrs Elizabeth Renner (my English teacher, role model and mentor), the pioneers of the Catholic schooling system and the founders of the Ahmadiyya Movement’s schools and health facilities, created a tradition of excellence that produced generations of leaders. Schools like Armitage High School, Gambia High School, St Augustine’s, St Joseph’s, Sukuta Secondary Technical, Crab Island Secondary Technical, Latrikunda Secondary Technical and Mrs Ndow’s primary and secondary schools were conveyor belts for talent.

Success in education was viewed as pivotal to national development and critical in our struggle to self-manage independently. Where did that spirit go? How did it vanish so badly? Who is responsible for our current social menace of illicit substance misuse, drug and alcohol related crime, poor security and the broken-down Gambia we no longer recognise?

The rise and fall of dictatorship in our country is the cornerstone of much of our ruin and vandalism of economic growth, self-sustenance and the rule of law. Our democratisation process came to a halt on 22 July 1994 when a group of soldiers led by Lieutenant Yahya Jammeh toppled Sir Dawda’s government.

They claimed they were cleansing the country of corruption and mismanagement and would return to barracks soon, but those promises never materialised. Jammeh installed a network of oppression driven by the police, the National Intelligence Agency and a death squad called the Junglers.

He consistently violated political rights and civil liberties for more than two decades.

Journalists and human rights defenders were arbitrarily arrested and detained for expressing themselves. Laws were amended to punish “false information” and “false news” with long prison terms and heavy fines.

In 2013, for example, giving false information to a public servant became punishable by up to five years in prison and a fine of 50,000 dalasis.

Protesters calling for electoral reforms in 2016 were brutally suppressed; some were killed, others tortured or disappeared. Education suffered, institutions eroded, and fear became a way of life.

The nation wholeheartedly welcomed Barrow to the highest office, embracing his leadership with optimism.

Little did we all know what was going to unfold? Barrow’s unexpected victory in the 2016 election marked a turning point. Since then, respect for fundamental freedoms has improved. New media outlets have sprung up, and Gambians enjoy greater freedom to criticise the government. Yet the legacy of Jammeh’s repressive laws hangs over us like a dark cloud.

Freedom House notes that the media environment is much improved, but several laws restricting freedom of expression remain in effect. Media outlets have been subject to arbitrary suspensions, and journalists have faced arrest or physical assault. Sedition laws stay on the books and could be used to criminalise criticism.

A colonial-era Public Order Act still requires event organisers to obtain police permits for public assemblies. Activists like Madi Jobarteh continue to face charges for social media posts. Even President Adama Barrow has sometimes warned of crackdowns on free speech, only to have his office retract those comments. The fear of expressing oneself politically remains ingrained as a reminder that our democracy is still fragile.

Meanwhile, successive poor and inefficient governments have mismanaged our economy. These governments have piled up debt and signed long-term contracts that mortgage our future. Private schools mushroom while public education languishes.

The next administration, whoever takes office after the 2026 elections, will inherit an enormous mess. Untangling the knots of debt, corruption, and institutional decay will require courage and vision. Recovery, self-sustenance, self-management and complete independence are not yet in sight. But if we look back at our early ideals and learn from our mistakes, perhaps the smiling coast can find its smile again.

By Salifu Manneh

For More News And Analysis About Gambia Follow Africa-Press