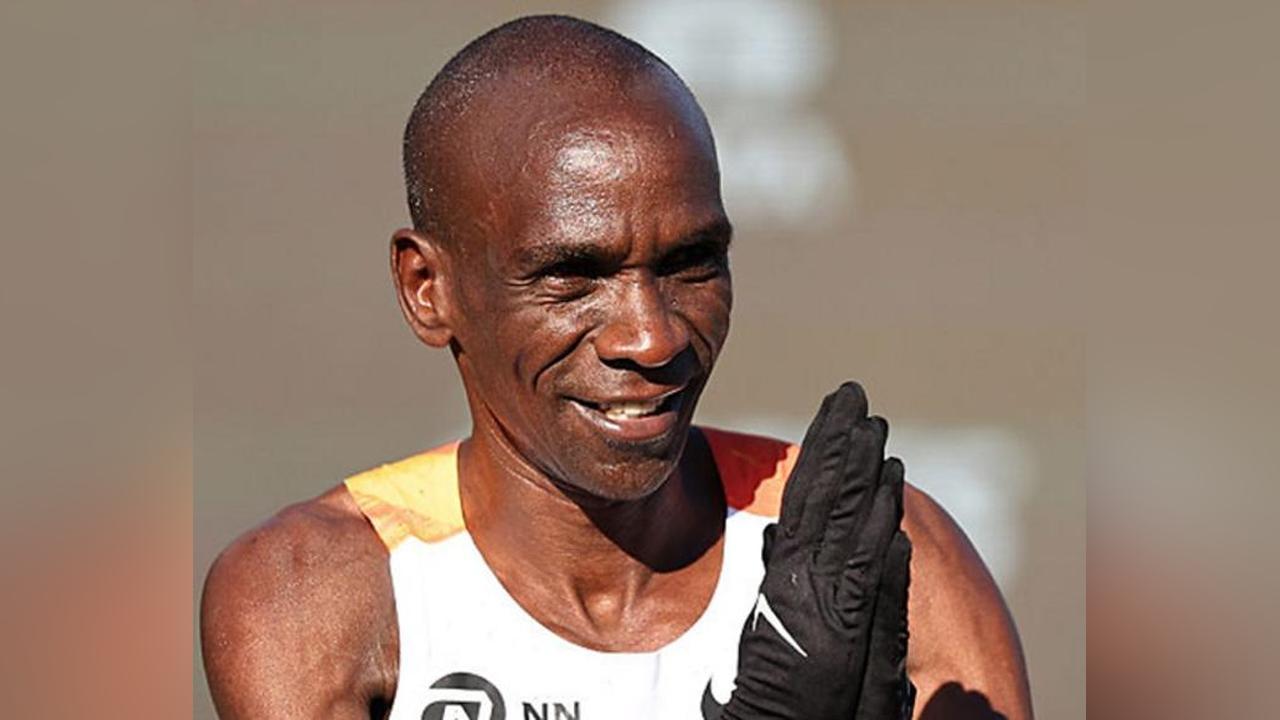

Africa-Press – Kenya. For more than two decades, Eliud Kipchoge ran with history on his back and won almost everything there was to win. He rewrote what the human body was believed capable of and became, by near-universal agreement, the greatest marathon runner ever.

Now the 41-year-old says the chase for medals and validation is over. “What I am doing is not retiring,” he says. “I am evolving. I am running for purpose.”

Kipchoge plans to take his running to the edges of the world with the Eliud Kipchoge World Tour – not to prove his greatness, but to give it away. Over the next two and a half years, the two-time Olympic champion will complete a marathon on all seven continents

“Running is the most universal sport,” he tells Newsday on the BBC World Service.

“It connects us all. With this project, I want to compete not only for records, but for the people.

“I want to inspire, to give back, and to remind everyone that no human is limited.” A legacy without limits To understand the significance of this moment, it helps to understand the magnitude of Kipchoge’s success. As well as those Olympic titles, Kipchoge’s honours have included a world title, 11 World Marathon Major victories and two official world records.

In one of sport’s most impressive feats, he became the first person to break the two-hour marathon barrier under special conditions in Vienna in 2019, clocking an unofficial time of one hour, 59 minutes and 40 seconds.

“If I look at the last 23 years, the highlight was making history,” he says.

“Not winning medals, not even breaking world records, but opening the minds of people around the world to believe that they are not limited in anything they are doing.”

That belief has become the anchor of his next chapter. The tour will operate under Eliud’s Running World, a long-term platform designed to promote participation in running while supporting global causes.

Each marathon will raise funds for the Eliud Kipchoge Foundation, which focuses on education, environmental sustainability and health. Kipchoge hopes to raise $1m (£739,000) at every stop, with projects tailored to local needs.

In Kenya, his vision includes building libraries across all 47 counties. In other cities, he wants the tour to leave behind tangible benefits, not just memories.

“I want to leave a legacy of education,” Kipchoge says.

“There is knowledge in books. If we want to think with the outside world, we need to get knowledge and understand how other people are thinking.” Running a marathon in the extreme Antarctic cold is not something Kipchoge sees as a stunt, but as a statement.

“It is about pushing your limits,” he explains. “I want to show the world that you can still push your limits in anything, even in the toughest conditions.”

Asked whether he is pushing himself too hard, his answer is characteristically direct. “Life is about pressing on,” he says. “The moment you stop pressing, it is no longer life.”

‘Nobody protects young athletes’ Kipchoge’s shift in mindset has been shaped not just by his success, but by what he has seen around him.

In recent years, he has become increasingly outspoken about the welfare of thousands of athletes who train as hard and dream as big as top stars but are left with little protection when they fall short.

“I am not satisfied with how athletes are being handled or how they are being paid,” he says.

“The sports world is making huge profits, but very little goes to the athlete.”

He believes the system creates a dangerous divide. Elite athletes earn disproportionately, while the majority struggle to survive – often without education, guidance or long-term support.

“It’s a real concern. And it’s a huge gap. If you do not appreciate somebody, they will move away,” Kipchoge says.

“And if they move away without knowledge, that is a real window for exploitation.”

Kipchoge rues the case of Evans Kibet, a Kenyan middle-distance runner who once dreamed of making it in the sport and is now being held in Ukraine as a prisoner of war after fighting for Russia.

Kibet says he was lured by promises of paid competition and employment, only to find himself conscripted and sent to the front line. His case has exposed how vulnerable athletes can be when opportunity is scarce and desperation high.

“It is unfortunate,” Kipchoge says.

“Young people want to support their families. They want a better life. But nobody protects them.” For Kipchoge, the issue is about systemic failure. “Talent does not look like talent if you do not nurture it,” he says.

Kipchoge argues that federations, agents and governing bodies have failed to invest properly in education, mentorship and safeguarding, particularly for athletes who do not immediately succeed.

“A diamond is just a stone,” he says.

“If it is crafted well, it becomes something valuable. If it is not, it remains just a stone.”

Kipchoge has long advocated for clean sport, warning that the pressure to succeed quickly has contributed to doping and ethical shortcuts. “People want quick riches,” he says.

“They do not see beyond sport. They do not value longevity.” He believes sport should be treated as a profession with a long horizon, not a gamble.

“If we teach young people to think about life beyond sport, to leave a clean legacy, then the sport will benefit,” he says. That philosophy extends beyond athletics.

Kipchoge has spoken about mentoring athletes in other disciplines including boxing, judo and rugby, particularly in communities where sport can provide structure, purpose and opportunity.

“We want to give young people options,” he says.

“Sport can change society, but only if it is handled in the right way.”

Even in lighter moments, Kipchoge’s values surface. Asked who he would choose for a no-pressure jog anywhere in the world, his answer is not another athlete.

“Barack Obama,” he replies. “Because he is a real human being.”

Between footballing greats Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, Kipchoge chooses Ronaldo – not for flair, but for work ethic. “He works hard every day to improve his talent,” Kipchoge says.

It is a familiar theme. Kipchoge values discipline over glamour, process over outcome and purpose over applause. Kipchoge says his world tour will not erase the competitive fire that defined his career. But the meaning behind that fire has changed.

“I have nothing more to prove to the world,” he says.

“What I want now is to sell the spirit of running to the next generation.”