In February, the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Mauritius among the 20 most democratic countries in the world. In March, the V-Dem Institute placed it among the world’s 10 most rapidly autocratizing countries.

Both ratings may have a point. After decades as a top-ranked democracy in Africa, Mauritius may be on the verge of a steep decline.

What do ordinary Mauritians have to say about it? Do they share analysts’ alarm that their democracy may be slipping away?

Findings from a 2020 Afrobarometer survey show that Mauritians have grave doubts about the state of politics in their country — and, in fact, were seeing red flags long before many analysts.

A flawed election signaled trouble

Mauritius’ 2019 national election, marred by accusations of irregularities and unfair practices, may have been a turning point. Since then, critics have accused the government of Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth of anti-democratic behavior, including restricting and harassing opposition parties and nongovernmental organizations. And corruption scandals tainted the country’s response to the coronavirus pandemic.

In April, the government’s Information and Communication Technologies Authority announced plans to decrypt and monitor all social media content, raising concerns about privacy and freedom of expression. And in May, police officers detained a prominent government critic, former attorney general Jayaram Valayden, charging him with violating the country’s coronavirus laws for organizing a small rally in support of the Palestinian people and peace in the Middle East.

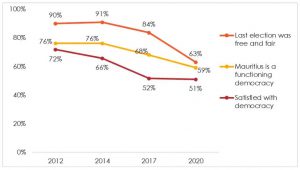

In the first Afrobarometer survey conducted in Mauritius nearly a decade ago, three-fourths (76 percent) of Mauritians said their country was a well-functioning democracy, one of the highest levels recorded across 35 African countries. But the two most recent surveys, in 2017 and 2020, reveal a 17-point decline in that assessment over six years, to just 59 percent. More than 1 in 3 Mauritians (36 percent) now see their country as either “not a democracy” or “a democracy with major problems” (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Is democracy in decline? | Mauritius | Afrobarometer surveys 2012-2020

Mauritians’ views on democracy and elections.

Satisfaction with democracy shows a similar pattern, except that the steep decline started even earlier. From a similarly high starting point — 72 percent said they were “fairly” or “very” satisfied in 2012 — satisfaction levels had already dropped six percentage points by 2014, and fell another 16 points over the next six years. In 2020, only about half of respondents (51 percent) report satisfaction with how the country’s democracy is working.

Trust in public institutions has faded

Although a majority (63 percent) in the 2020 survey still report confidence in the quality of the last (2019) election, this is also down sharply from 90 percent in 2012’s survey, which asked about views on the 2010 election. Over the same period, perceptions that the country is going in the right direction have declined from a slim majority (53 percent in 2012) to just 41 percent in 2020.

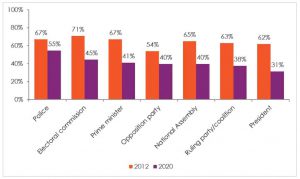

Figure 2: Trust in institutions | Mauritius | Afrobarometer surveys 2012-2020

Percent of Mauritians who said they trust these institutions “somewhat” or “a lot.”

Mauritians’ deep misgivings about what is happening in their country stand out starkly when it comes to plummeting institutional trust (Figure 2). A decade ago, all key governing institutions enjoyed the trust of a solid majority of citizens — including the prime minister (67 percent), the National Assembly (65 percent) and the ruling coalition (63 percent). By 2020, trust in each of these institutions had dropped by 25 percentage points or more.

In short, while international experts have only recently started to raise the alarm about the threatened status of democracy in the country, ordinary Mauritians seem to have been aware that trouble was brewing for several years.

Though increasingly unhappy about political conditions in their country, Mauritians remain strongly committed to democracy, our surveys report. Support for democracy as the best system of government has declined from a high of 85 percent in 2012, but it remains robust at 76 percent in 2020.

And overwhelming majorities reject authoritarian alternatives such as military rule (90 percent), one-man rule (90 percent) and one-party rule (95 percent) — and support elections as the best system for choosing the country’s leaders (83 percent).

Will this support protect Mauritian democracy?

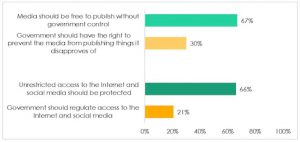

One important strength may be Mauritians’ belief in the free flow of information (see Figure 3). Two-thirds (67 percent) of citizens endorse “the media’s right to publish any views and ideas without government control,” and a similar proportion say the country’s media is indeed “somewhat” or “completely” free. The World Press Freedom Index ranks Mauritius 61st in the world, citing political polarization and unfair treatment of opposition-friendly outlets among the media’s problems, but says news outlets enjoy the freedom to be “very outspoken.”

Figure 3: Views on media/social media freedom | Mauritius | Afrobarometer surveys 2020

Percent of Mauritians who “agree” or “agree very strongly” with each survey statement.

Social media may play a critical role, too. Seven in 10 Mauritians (69 percent) report getting news from social media on a daily basis — that’s by far the highest level recorded by Afrobarometer, and more than double the continental average of 29 percent across 32 countries. This may explain both the government’s interest in surveilling social media and the widespread public concern about these plans.

Two-thirds (66 percent) of citizens support unrestricted public access to the Internet and social media, compared with just 21 percent who think the government should regulate access. Amid government efforts to limit political discourse, social media may become an increasingly valuable — and contested — tool for sharing information.

In Mauritius, as in other threatened democracies, one crucial question will be whether popular commitment to democracy, perhaps coupled with the free flow of information, will be enough to stop the slide toward a less democratic system.