Africa Press-Nigeria:

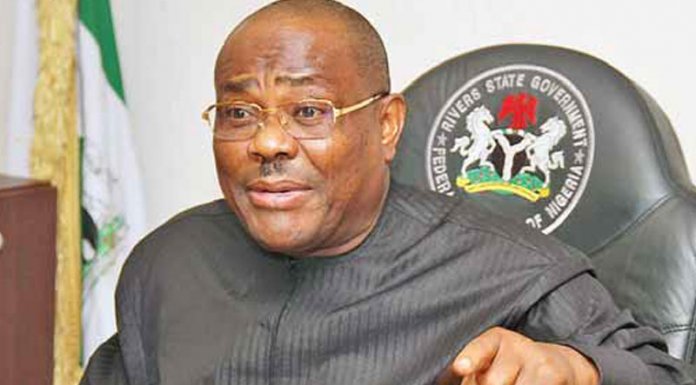

Let me begin by saying that the views expressed in this article are not solely targeted at Governor Nyesom Wike of Rivers State. It extends to the Nigerian Government and all governors in Nigeria that have taken restrictive actions similar to the fiat issued by Wike banning entry into and exit from Rivers State by air, land or sea. I am using Rivers State as a case study given the far reaching dimension of Wike’s statement.

Some public commentators, including unfortunately some lawyers, have been making this ridiculous argument that laws can be totally dispensed with and that constitutional and statutory provisions are useless when there is emergency. They base their argument on what they vaguely call “the doctrine of necessity”. I find this argument very offensive and irritating. But I will just make this brief remarks in response.

The duplicity of this argument is exposed by a simple reply: If there is emergency in Nigeria, whether due to external or internal aggression, natural disaster, outbreak of infectious diseases or any other cause, the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), empowers the President to declare a state of emergency throughout the federation or any part thereof.

One cannot say that there is emergency because of COVID-19 and at the same time repudiate my call for the declaration of a state of emergency. That amounts to approbating and reprobating. It is a case of speaking from both sides of the mouth. The framers of the constitution were not stupid when they enacted section 305 of the constitution which imbued the President with extensive powers to declare a state of emergency when the need arises.

Also, there are ample provisions under our extant laws on how to respond to emergencies. The legally permissible thing for any democratic and sensible government to do is to simply invoke the extant laws or to pass new emergency laws.

In the United States, President Trump declared a national emergency throughout the United States. Not less than 48 States in the US have declared emergency. The US Congress recently passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Trump also invoked the Defense Production Act. Few hours ago, the US Congress passed yet another emergency relief Bill to tackle coronavirus. The United Kingdom parliament on Monday passed emergency legislation to give the government the needed power to enforce restrictions and fight coronavirus. Other serious democratic countries have also declared national emergency and passed emergency legislations.

Why should the case of Nigeria be different?

Those who say that we should not talk about laws when there is emergency are either advocating the enthronement of anarchy or oblivious of what it means to run a constitutional democracy.

It is either we operate under the rule of law or we perish under the rule of force.

The so-called doctrine of necessity referenced by some commentators which they falsely claim empowers the government to ignore laid down rules during crisis is a legal fiction under a constitutional democracy.

The expression “doctrine of necessity” came into our lexicon in Nigeria in 1970 in the famous case of Lakanmi versus Attorney General of Western Region. I will not go into the long facts of the case. I will only highlight few key points from the judgment to buttress my submissions.

First, the Supreme Court in Lakanmi’s case decided in favour of fundamental rights and rejected the argument of the military regime that it can take away any fundamental right by Decree, Edict and use of force without legal challenge.

Second, the military sought to take away Lakanmi’s properties by Decrees and Edicts (laws) not by force. The military regime in the West at the time passed the Public Officers and other Persons (Investigation of Assets) Edict No 5 of 1967 under which Lakanmi was investigated and found guilty of corrupt practices.

As brutal as military regimes were, they mostly relied on draconian decrees and edicts to violate the rights of citizens. It is therefore palpably shocking that citizens in a ‘democracy’, will support the wilful derogation of their fundamental rights without appropriate legal framework enabling same.

Third, the Supreme Court held that the military regime was not a revolutionary regime but a temporary emergency regime which came about by doctrine of necessity due to abdication by the civilian government. Note that the military enacted Decrees before it sought to take over Lakanmi’s properties. Therefore, citing the “doctrine of necessity” to say that laws are dispensable is unfounded.

Fourth, the so-called “doctrine of necessity” has no basis in a constitutional democracy. We cannot talk about necessity when there are relevant legal provisions to cater for emergency cases. The only necessity in such cases is invocation of the law. There is no judicial precedent that supports the argument that laws can be dispensed with during emergency; except there is a special constitutional or statutory provision in that regard.

Fifth, following the Supreme Court decision in Lakanmi’s case, the Gowon regime swiftly annulled the judgment by promulgating Decree 28 of 1970 – The Federal Military Government (Supremacy and Enforcement of Powers) Decree.

When the National Assembly on February 9, 2010 passed a resolution empowering the then Vice President Goodluck Jonathan to assume the functions of the office of President in an Acting capacity due to the critical illness of the late President Yar’Adua, they did not act completely without the law. They relied on the extant Section 145 of the constitution at the time. The National Assembly only referenced the “doctrine of necessity” because Yar’Adua did not transmit a physical letter to the National Assembly.

It is therefore wrong to cite that resolution by the National Assembly as a validation of the proposition that doctrine of necessity can supplant the law. It was the lacuna in Section 145 of the constitution (which was later amended), that prompted that consequential resolution. If there was no lacuna, the National Assembly would not have said anything about a nebulous doctrine of necessity.

Section 305 of the constitution and the Quarantine Act are very express on how the government should address threats to public health and public safety. There is no lacuna whatsoever. It is therefore disingenuous to talk about doctrine of necessity due to coronavirus when the laws are not in doubt as to what should be done.

I dare say that there is no court in Nigeria today that will accept the ridiculous argument that validly made laws can be dispensed with based on the so-called “doctrine of necessity”.