Tom Ndahiro

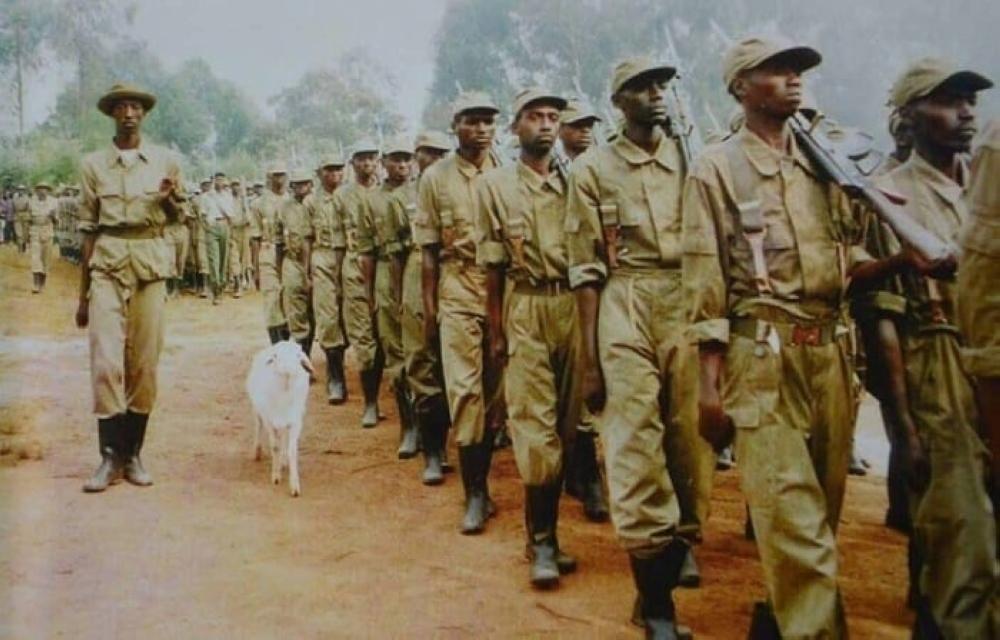

Africa-Press – Rwanda. Every year, Rwanda marks July 4 as Liberation Day. It is a day of earnest celebration, of memory, of national rebirth. It commemorates the day the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA)—an armed wing of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), stopped the Genocide Against the Tutsi and ushered in a new chapter for a nation that had been marinated in hate.

But amid the commemorations, one dimension often goes unspoken, even if its absence is deeply felt: the liberation from weaponized music—songs crafted to indoctrinate, dehumanize, and divide. It was not just territory that had to be reclaimed or lives that had to be saved; Rwanda had to be rescued from the poisonous rhythms that danced on airwaves and echoed in schoolyards, churches, and bars.

That is why December 31, 2001, is a day of immense historical and symbolic importance. On that day, Rwanda formally retired its old national symbols: the flag, the coat of arms, and the anthem Rwanda Rwacu. It was the last day of hypocrisy, of officialized hatred dressed as patriotism.

The very next day, January 1, 2002, marked not just the beginning of a calendar year but the birth of a new Rwanda. Not just a new year but a new era. A new flag of hope and reconciliation. A new coat of arms that emphasized unity and development. And most importantly, a new national anthem—Rwanda Nziza (Beautiful Rwanda).

Gone were the lines glorifying militants. Gone were the subtle divisions, the coded supremacism. The new anthem sang of togetherness, peace, and truth—not as an oxymoron, but as a mission.

It was a cleansing. A renunciation. Rwanda did not just silence the guns of 1994; it dismantled the ideological machine that fired them.

From the very beginning of Rwanda’s so-called independence in 1962, a fake sovereignty manufactured by Belgium through manipulated elections and violent purges, a political ideology steeped in Hutu supremacy was not only installed but carefully choreographed to seem legitimate.

Unlike other African nations that achieved independence through gradual institutional reform or clear nationalist leadership, Rwanda’s “republic” was declared while still under Belgian colonial control.

Take Tanganyika, now mainland Tanzania for instance: it gained independence on December 9, 1961 and became a Republic only a year later, in 1962, after an internal constitutional process.

Rwanda, by contrast, was declared a Republic on September 25, 1961—before even attaining independence on July 1, 1962. How does a colony become a Republic before it becomes a nation? The answer lies in colonial manipulation.

This engineered “Republic” was the result of Belgium’s strategy to install a compliant ethnic-majority regime, under the guise of democratic choice. Belgium’s colonial officials, led by Colonel Guy Logiest, organized sham communal elections and a referendum on the monarchy in 1961.

The political objective of the Kingdom of Belgium was clear: destroy the Rwandan monarchy and hand over state power to the manufactured “Hutu majority”—particularly to Kayibanda’s Parti du Mouvement de l’Emancipation Hutu (PARMEHUTU), which had formed in 1959 and was openly anti-Tutsi. For a moment—just imagine, a Republic created by a Kingdom!

It is no coincidence that this political shift was not simply documented in decrees or law books—it was sung. Music became the ideological glue of the new regime. PARMEHUTU understood that to entrench their version of truth, they had to do more than govern. They had to sing.

PARMEHUTU, the ruling party under President Grégoire Kayibanda, mastered a powerful tool of mass indoctrination: music. That is how Hutu Power began—not just in pamphlets or speeches, but in lyrics, melodies, and choruses.

In fact, the most effective medium to penetrate the minds of the uneducated and even indoctrinate the literate was music. Songs could go where ideologues could not. They seduced the soul, bypassed critical thought, and embedded genocidal ideologies in memory like lullabies.

They had to make hate harmonious in music. And so they did, through a musical troupe called Abanyuramatwi, literally “those who soothe the ears.” But rather than comforting, these voices were devious. They disguised hate in the rhythms of patriotism.

Abanyuramatwi

The soothing voices of hatred or the Abanyuramatwi ensemble, under the leadership of Michel Habarurema—was not just a cultural arm; it was a psychological weapon. Their songs provided the sound effects to the PARMEHUTU regime’s methodical and schematized rewriting of Rwanda’s history and social hierarchy.

They composed songs that were deceptively lovely, melodically pleasing, and easy to memorize—but within them, genocidal ideology was laced like poison in honey. The music normalized division, glorified discrimination, and romanticized ethnic violence. These songs aired on Radio Rwanda and were played in schools, churches, and at national celebrations. They were part of everyday life, and thus, indoctrination was not occasional—it was constant.

Among these songs, three stand out for their sheer toxicity: Rwanda Rwacu (Our Rwanda), Turatsinze (Victory is Ours), and Jya Mbere Rwanda (Go Forward Rwanda). These songs provide a window into how Hutu Power ideology was constructed, disseminated, and sanctified.

Rwanda Rwacu or Our Rwanda was not composed but crafted to praising PARMEHUTU militants and preaching hypocrisy. This was the Rwanda’s national anthem from 1962 until December 31, 2001. At face value, it appears patriotic.

But dissecting its lyrics tells how it weaponized words like Republic, Democracy, and Feudalism to mislead people and divide them. These terms were not used in their conventional meanings; they were redefined to serve a political agenda.

The most disturbing stanza is the first: “I praise the Militants / Who established an unshakable Republic.”

In Kinyarwanda, “Nsingiza abarwanashyaka bazanye Repubulika idahinyuka.” The word nsingiza is not neutral. It’s the same word used in religious songs to glorify God. Here, it glorifies political militants—many of whom had blood on their hands.

These militants were not freedom fighters; they were architects of ethnic cleansing. They led pogroms against Tutsis in 1959, 1961, 1963, and 1973. Yet the anthem elevated them as near-divine heroes. This was the anthem that schoolchildren were required to sing, effectively internalizing the glorification of killers as national martyrs.

The second stanza reads: ‘The Republic has uprooted Feudalism / Colonialism has disappeared for good / Be strengthened, O Democracy.’

But what do Feudalism and Democracy mean here? In the PARMEHUTU regime’s lexicon, Feudalism became a code word for Tutsi. It did not refer to a socio-economic structure, but to a racialized enemy.

Republic meant the destruction of the Tutsi leadership class. Democracy didn’t imply pluralism or human rights—it was shorthand for ethnic majoritarianism. One ethnic group, the Hutu, ruled. Others were excluded or eliminated. Thus, “Democracy” became the dictatorship of one ethnic identity.

The anthem’s third stanza pretends inclusivity: ‘We all fought to gain it—Tutsis, Twas, and Hutus / And you, naturalized Rwandans.’

But this was nothing but plain propaganda. Tutsis were fleeing for their lives during this so-called struggle. The “we” here is political fiction. By suggesting that Tutsis fought for the Republic, the regime exonerated itself and gaslit its victims.

Turatsinze ga ye!

In this song, Abanyuramatwi and PARMEHUTU sang victory by ethnicity and not by nationhood.

This song, “Victory is Ours,” was written to celebrate the rigged 1961 referendum and communal elections. The chorus: ‘Victory is finally ours! / The referendum… has been won by PARMEHUTU!’

This triumphalist tone is not national at all. It is tribal. The real essence of the song and the venom is concentrated in the second stanza: ‘Gahutu, wherever you are, rejoice / The debates are over / Rwanda returns to its rightful owners/ Gahutu, triumph without dispute!’

This is not politics. This is ethnic supremacism. The term “Gahutu” is invoked like a war cry. The reference to “debates are over” is a declaration that political pluralism is dead. The country has been conquered, and all who oppose this narrative are enemies.

The message is crystal clear: Rwanda belongs to the Hutu. The song frames the Tutsi as usurpers, foreign elements who had taken something not theirs. It was a call to all Hutus to unite in reclaiming what they believed was stolen.

Then comes the veneration of Kayibanda in the final stanza: ‘Gahutu, wherever you are, bask in well-being/ Kayibanda, whom we elected, has just freed us from the worst servitude/That was consuming Rwanda!’

The “servitude” here is not Belgian colonialism; it’s code for the period when the Tutsi monarchy existed. Colonialism is used as a veil. In truth, the enemy is the Tutsi. The rewriting of history is shameless. By framing the Tutsi as co-colonizers, the song justifies their exclusion and eventual extermination.

A march to madness

The third song, Jya Mbere Rwanda (Go Forward Rwanda), is a masterpiece of euphemism. Its first stanza introduces the term Interahamwe as a badge of unity:

Go Forward, Rwanda / You are supported by men who are Interahamwe, members of PARMEHUTU.

At first glance, INTERAHAMWE simply means “those who are united toward one goal.” But we now know what that goal became: extermination. In 1992, this very term would be resurrected by the MRND regime as the name of the genocidal militia that hunted down and slaughtered Tutsis. But even in the 1960s, the term carried an undertone of militancy and exclusion.

The second and third stanzas are diabolically cunning:

‘What was Rwanda like? / The White man and the Tutsi had swallowed it up / By sidelining the Gahutu who was the true owner.’

‘The White man spoke and the Tutsi agreed / The latter only wanted one thing: to survive until tomorrow.

Here, the colonialist and the Tutsi are made synonymous. This historical lie is repeated like doctrine. In fact, many colonialists saw the Tutsi elite as a means to their own ends, and later turned against them in favor of populist Hutu nationalism. But by fusing the Tutsi and the colonizer, the song casts them both as the oppressors. This narrative provided the moral justification for ethnically-targeted violence.

The fourth and fifth stanzas venerate Kayibanda and the so-called Hutu revolutionaries:

‘Gahutu prevailed, democracy spread / Let us all applaud Kayibanda and his companions.’

This was not democracy. This was majoritarianism enforced by expulsion, intimidation, and mass killings. From 1959 to 1973, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis fled to neighboring countries. Those who remained lived as second-class citizens.

The sixth stanza adds a hypocritical flourish: ‘What is Rwanda like now? / Every Rwandan is free / And every foreigner feels welcome.’

The regime had already rendered Tutsi refugees stateless. And yet, this song dares to claim that foreigners are welcome. It is a sadistic lie.

The final stanza mocks the dispossessed: ‘If only we could bring back one of those enemy-refugees-of-Rwanda / To see Gatutsi, Gatwa, and Gahutu sitting together / He would have nothing left to say / Except to gnash his teeth.’

This is not a reconciliation tune. It is a cruel taunt. It tells refugees: you are irrelevant. What you think is your Rwanda, has moved on without you.

How songs entered the mind

Music, in this context, was not entertainment. It was propaganda. It reached people where newspapers could not. It made hatred melodic, memorable, and digestible. Songs like these were repeated in schools, at public functions, on national radio. They were installed into memory like catechisms. They made genocidal ideology singable.

These songs were not just played—they were learned, recited, internalized. Children sang them in school assemblies. Church choirs unknowingly harmonized the ideology. Refugees born in exile picked up the tunes from Radio Rwanda without knowing their deeper meaning.

When children of Tutsi exiles began humming these songs, their parents would scold them—not out of cultural contempt, but from traumatic recognition. They knew what those lyrics really meant. As these children grew older in exile, they came to understand the duplicity: that a song called “Our Rwanda” was actually a hymn of division—praising criminals. That, a song called “Go Forward Rwanda” was a marching order to segregation, and that a chorus of “Victory is ours” was the anthem of ethnic cleansing.

These songs were serenades of ethnic superiority. They taught a child that the Gahutu was the rightful owner of Rwanda, and that the Tutsi was a foreign usurper. The Interahamwe weren’t a militia yet, but already they were being praised as Rwanda’s future.

The indoctrination was complete. A generation was raised not with open hatred, but with euphemisms set to melody. This is what made the ideology enduring and effective. You can censor a book. You can imprison a journalist. But how do you silence a song already memorized by an entire population?

When songs became sermons of hatred

One of the most spiritually perverse aspects of Rwanda’s musical indoctrination under Hutu Power was the misuse of theological language and symbolism. In the anthem Rwanda Rwacu, the line “I praise the Militants who established an unshakable Republic” uses the Kinyarwanda verb gusingiza—a term deeply rooted in religious tradition and reverence.

It is the same word one would use in praising God: Gusingiza Imana. This is not casual vocabulary. In Christian liturgy, it connotes sacred adoration. To direct this sacred language toward political militants is not merely inappropriate—it is sacrilegious.

In Rwandan culture, gusingiza is used in moments of exceptional honor. Traditionally, it was reserved for people who had performed an extraordinary deed benefiting society—heroes, benefactors, or sages. The one who is ‘gusingizwa’ is not just acknowledged—they are exalted.

In Christian liturgy, especially among Catholics, gusingiza reaches its loftiest height in hymns like the Mary’s Magnificat, with a refrain: ‘Let us praise the Lord, for He has done great things.’ Christians also believe angels and saints team up in heaven to praise God. To hear gusingiza is to hear a sacred chorus. It is a word that belongs in temples, not tribunals.

And yet, in the national anthem, this sacred verb was hijacked to glorify “militants”—the very people who laid the foundations for exclusion, persecution, and mass violence. The anthem did not merely acknowledge them—it elevated them, making them the moral equivalents of saints or even Vicars of God. It was not enough for these architects of hatred to be feared or obeyed; they had to be venerated.

What makes this more damning is that nearly every organized religion in Rwanda—Catholic, Protestant, even certain Pentecostal sects—participated in this chorus of false sanctification. The militants of PARMEHUTU, far from being condemned from the pulpit, were honored in a national anthem sung in schools, churches, and national feasts.

In effect, they received the kind of collective liturgical glorification once reserved for martyrs or apostles. They were canonized by nationalism and baptized in the refrain of genocide.

This blasphemous equivalence essentially elevated genocidal architects into saints. The militant class that organized massacres and institutionalized ethnic discrimination were not just thanked—they were glorified, even canonized.

The song created a moral inversion: virtue became vice, and vice became virtue. Praising those who tore the country apart was not just accepted; it was ritualized through repetition. This mirrors what theologians might call the “diabolical liturgy”—where acts of evil are draped in the robes of righteousness.

The result was a nation spiritually anesthetized to evil. Where chants of division were harmonized like hymns, and the sacred became subverted into the service of segregation.

Historical parallels

Rwanda’s use of music as a propaganda tool is not unique. Across history, totalitarian regimes and racist ideologies have used music to entrench control, dehumanize opponents, and normalize violence.

In Nazi Germany: The Third Reich commissioned songs like “Die Fahne Hoch” (Raise the Flag), known as the Horst-Wessel-Lied, which became a Nazi anthem. Like Rwanda Rwacu, it changed political loyalty into spiritual destiny. Hitler Youth were taught patriotic songs that glorified Aryan supremacy and the Führer. Music was used in schools, rallies, and broadcasts to condition minds.

In the American Confederacy, songs like “Dixie” sentimentalized the Southern slaveholding way of life, wiping away the inhumaneness of slavery behind joyful melodies. After the Civil War, Lost Cause ideology found its way into hymns and folk songs that subtly defended white supremacy.

During Apartheid South Africa—Afrikaner nationalist songs, often sung in Afrikaans, extolled the virtues of Boer ancestry and the ‘Divine right’ to rule. These songs reinforced apartheid ideology under the guise of cultural preservation.

Serbia in the 1990s: Turbo-folk music, heavily promoted by Slobodan Milošević’s regime, glorified Serbian nationalism and often contained veiled (or open) threats against Bosniaks, Croats, and Albanians. Music videos featured paramilitary imagery and echoed genocidal slogans.

In each of these cases, music allowed ideology to bypass rational scrutiny. It made hate feel like heritage. Rwanda’s case, however, is arguably more insidious because the entire foundation of the first republic was narrated through song. Unlike other regimes where propaganda was a side project, in Rwanda music was the main sermon.

Rwanda Nziza as musical liberation

The shift from Rwanda Rwacu to Rwanda Nziza was not just a change in lyrics—it was a political, moral and psychological exorcism.

The new anthem opens with: ‘Rwanda our beautiful and dear country / Adorned of hills, lakes and volcanoes / Motherland would be always filled of happiness / Us all your children: Rwandans / Let us sing your glory and proclaim your high achievements.’

There is no mention of ethnicity, no glorification of felonious militants, no triumph of one group over another. Instead, the land itself—its beauty, its serenity—is the unifying image. Where Rwanda Rwacu sang of Republics “won” through exclusion, Rwanda Nziza sings of unity “born” through reconciliation.

Later lines emphasize: ‘You overcame the hardships / That weighed heavily on you / And brought us peace again.’

This is a glaring contrast. The old anthem demanded praise for those who created divisions, discrimination, persecution and genocide. The new anthem acknowledges pain, loss, and hardship—and then offers healing. It does not pretend peace was always there. It recognizes that it had to be rebuilt.

The final stanza of Rwanda Nziza invokes future generations: ‘Our valorous ancestors / Gave themselves bodies and souls / As far-sighted as they were / For you to become a good heritage / Even we your children / We commit ourselves to valuing your immense legacy.’

Here, valorous ancestors—is not a euphemism for militants or a specific ethnicity. It is an inclusive term. It opens the narrative to everyone who fought for justice, dignity, and unity. The new anthem dignifies rather than deifies. It invites reflection rather than ritualism.

End of the songs of supremacism

Music in Rwanda was once a tool of indoctrination, a delivery system for division. The state-sponsored songs of the first and second republics used rhythm to reinforce racism, and melody to make murder seem noble.

But Rwanda changed the channel. When the country adopted Rwanda Nziza on January 1, 2002, it wasn’t just the end of a song—it was the end of an era. The soundtrack of supremacy was silenced. And in its place came a song of sincerity.

Today, Rwandan youth must continue to carry that melody forward—not with blind repetition, but with conscious reflection. They must remember that music, like language, can bless or curse, build or destroy.

And may they never forget: the day the music died in Rwanda, was the day a new nation with a different mentality was reborn.

Yet, we must not simply say the music changed. We must say: the ritual of hate was disrupted. The saints of supremacy were dethroned from their musical altars. The choirs of nationalist praise were disbanded. No longer would mass be followed by melody that sanctified murderers. No longer would the nation’s children rise in classrooms to praise men who had weaponized ethnicity.

It is a profound irony—no, a scandal—that for nearly four decades, Rwanda’s most sacred national ritual was the musical canonization of political criminals. For thirty-nine years, Rwandans sang not to uplift their better angels but to serenade their worst demons. If that is not spiritual perjury, what is?

Let it be said: when Rwanda adopted Rwanda Nziza, it did not merely swap verses. It exorcised a demon.

And to those who look back at the “glory days” of the first Republic with nostalgia, humming those old tunes in private, we must ask: Is it really patriotism you’re singing? Or is it just hatred in harmony?

Because if your best memories are musical odes to oppression, perhaps silence is your greatest contribution to peace.

To the young generation of Rwanda: be vigilant. Propaganda no longer needs cassette tapes. It can live in YouTube videos, in nostalgic songs, in rewritten TikTok skits, in romanticized tributes to the past.

Ask always: What are you singing? Who wrote it? What history does it serve? Never again should a song be a weapon. Never again should melody mask murder. Your voices are Rwanda’s future—let them be voices of light.

And when you sing, sing not of division but of unity and dignity. Not of conquest, but of compassion.

So yes, Rwanda was liberated from the killers. But equally important, it was liberated from their soundtrack. And for that, let us raise not a song of praise—but a silence of truth.

Let that silence be permanent. Let our voices, and our music, only ever again soothe the ears—and the heart.

Source: The New Times

For More News And Analysis About Rwanda Follow Africa-Press