Africa-Press – Zambia. Languages are more than words.

They are living vessels of history, memory and identity.

To speak one’s mother tongue is to connect with the voices of ancestors, to carry forward centuries of wisdom and to affirm belonging in a world that often erases difference.

When a language dies, it is not just vocabulary that disappears, it is an entire worldview, a map of meaning and cultural manual for a treasure lost forever.

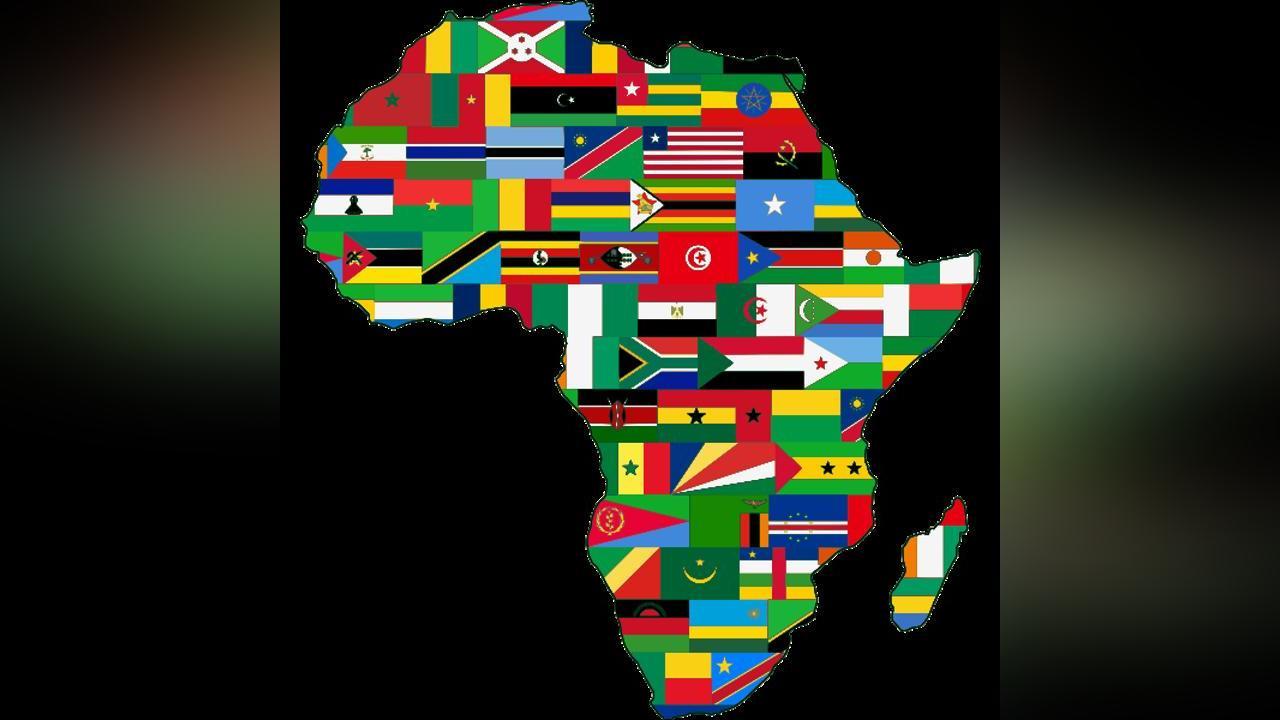

Across Africa and the world, indigenous languages such as IsiXhosa, Ibani, Gokana, Igbo, Hausa, Yoruba and IsiNdebele are under pressure from globalisation and the dominance of English, Spanish and Mandarin.

English in particular has become the world’s most common second language and the primary medium of the internet.

While this global reach can feel empowering, it also comes at a price.

It subtly conditions us to sideline our native tongues, replacing the intimacy of heritage with the convenience of universality.

The effect of danger is real.

Between 1950 and 2010, 230 languages became extinct, according to Unesco.

Today, a third of the world’s languages have fewer than 1 000 speakers left.

Every two weeks, another language dies with its last speaker.

By the next century, between half and 90% of the world’s languages could vanish.

Imagine the silencing of thousands of ways of seeing the world, the ecological knowledge of farmers, the spiritual practices of healers, the poetry of oral storytellers, all erased because their languages fell silent.

When we lose a language, we lose more than communication.

We lose a way of understanding the land, a philosophy of community, a rhythm of life that no textbook can replace.

Traditional ecological wisdom, for instance, is encoded in indigenous languages, knowledge of seasons, plants, rivers and healing that modern science increasingly turns to for solutions.

Without the language, much of that wisdom becomes inaccessible.

Yet this crisis is not inevitable.

There is power in reclaiming and celebrating our languages.

Studies have shown that individuals who speak their mother tongue report higher self-esteem and a stronger sense of belonging.

Speaking IsiNdebele in Bulawayo, isiZulu in Soweto, Yoruba in Lagos and or Shona in Harare is not just about words, it is about identity.

It grounds us, anchors us to our communities, and reaffirms that our cultures are worthy of survival.

We already have inspiring examples across the continent.

Kiswahili, once dismissed as merely “regional,” has now been elevated to the status of an official African Union language.

Nollywood, Africa’s largest film industry, continues to produce world-class films unapologetically in Yoruba and Igbo, showing the world that African languages can dominate cinema without translation.

In South Africa, isiZulu and isiXhosa musicians are not only topping local charts but also gaining international audiences by singing in their mother tongues, proving that authenticity is marketable.

These stories remind us that indigenous languages are not obstacles to progress, they are powerful tools of influence and export.

I have experienced this truth personally.

Through cultural exchange programs and community dialogues in both Africa and Europe, I have met citizens from the United States and Asia who were eager to learn about African languages and traditions.

I have shared with them the depth of isiNdebele, our practices, and our philosophies.

What struck me most was not just their curiosity, but the pride I felt in standing as a custodian of a language that carries my people’s history.

It reminded me that our indigenous languages are not barriers to global citizenship, they are contributions to global richness.

The challenge before us is clear.

We must resist the erosion of our tongues and invest in their revival.

Governments should create policies that elevate indigenous languages in schools, media, and technology.

Creatives like poets, musicians, filmmakers amongst others, must use these languages unapologetically in their work, normalising their beauty and power.

Families must speak to children in their mother tongues so the chain of memory is not broken at the household level.

Languages will only survive if they are spoken, sung, written and lived. Each word uttered in isiNdebele, Yoruba, or Igbo is an act of resistance, a statement that we refuse to vanish quietly into globalisation’s shadows.

Indigenous languages are our power.

They carry our memory, our wisdom, and our future. To reclaim them is to reclaim ourselves.

To speak to them is to declare that we are here, unbroken and unafraid to stand tall in a globalised world.

For More News And Analysis About Zambia Follow Africa-Press