With hindsight, we now seem to agree that most of us, policymakers included, underestimated the depth of Zimbabwe’s economic challenges last year.

The performance of the economy last year seems to suggest that we lacked a deeper understanding of the true nature of the challenges, and, therefore, the potency of the reforms, which were introduced in October 2018.

Our economic problems are long-term and structural in nature. They formed over a long period of time, spanning over two decades and cannot be fixed overnight or over a short period of time.

Importantly, they are beyond economics and finance. Therefore, they can’t be fully tackled by economics and finance solutions only.

Barring the effects of economic shocks from the devastating drought and Cyclone Idai, it appears policymakers were overambitious in their 2019 projections, which were understandably based on their view of the efficacy of fiscal and currency reforms.

They also failed to anticipate the impact of monetary reforms, namely liberalisation of the exchange rate, which, arguably, had become long overdue.

The exchange rate was unrealistically maintained at par to the US dollar for a long time through unsustainable subsidies, including currency subsidies, arguably, as a soft lending strategy of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ).

Importantly, it appears policymakers failed to grasp the effects of administrative challenges in Government and State-owned institutions, which is a huge drawback on policy implementation, coordination and effectiveness.

Some managers in Government and at corporate level do not understand the current reform thrust as well as priorities of the day, which has seen them make economically unviable and costly decisions to the detriment of the whole economy.

Worryingly, some of them live in the past. They resist change, block or sabotage progress, are corrupt or have vested interests.

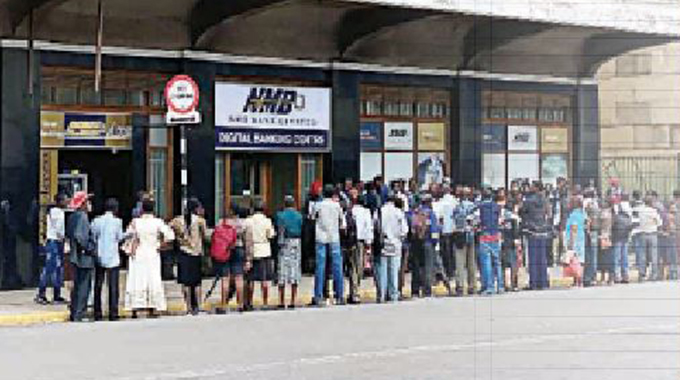

Equally worrying is the current political impasse, which stifled economic reforms. The impasse has also compounded the confidence crisis typified by deep distrust in Government policies and lack of cooperation in some quarters.

More still needs to be done to tackle corruption. There is a perception that what has been done is inadequate because graft is now everywhere and at all levels of the society.

Like what happened to China when it initiated reforms in 1978, a more radical and big bang approach is needed. Anything short of that may not inspire confidence.

Despite all these structural issues, our policymakers managed to convince international financial institutions (IFI), namely the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), who have normally taken a pessimist view on Zimbabwe, about the efficacy of the reforms in place to get the economy back on a recovery path.