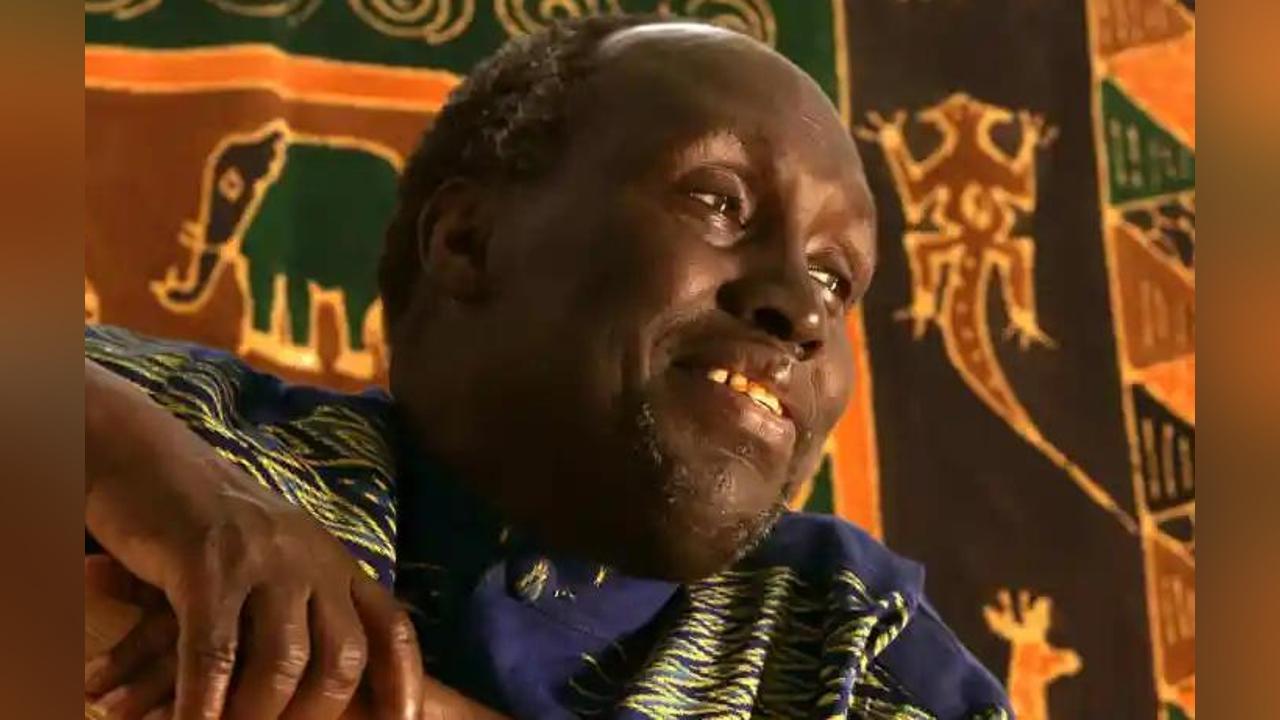

Africa-Press – Angola. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was more than an author. He was a revolutionary wordsmith, a fierce defender of cultural identity, and a towering intellectual whose life’s work served as both a mirror and a map for Africa’s journey toward self-liberation.

His pen did more than write novels—it carved out space for African voices to speak back to centuries of colonial domination, cultural erasure, and political oppression.

Across decades, Ngũgĩ wielded literature as a weapon against injustice, using storytelling not simply to entertain, but to awaken consciousness and challenge power.

His death marks the end of a remarkable era in African letters, but his spirit will forever echo through libraries, classrooms, and movements across the globe.

His legacy stands tall, like a baobab rooted deep in the soil of our collective memory, unyielding, enduring, and ever-reaching toward the sky.

Born James Ngugi in 1938 in Kamiriithu, near Limuru in colonial Kenya, Ngũgĩ grew up during one of the most turbulent periods in East African history.

As a young boy, he witnessed the Mau Mau resistance against British colonial rule, a conflict that would later become central to much of his fiction. His early life was marked by hardship, upheaval, and resilience, which deeply shaped his worldview and instilled in him a lifelong commitment to justice.

Ngũgĩ’s literary career began in English, the language of colonial instruction, but he quickly turned that very tool of domination into a medium for African empowerment.

His debut novel, Weep Not, Child (1964), was the first English-language novel published by an East African.

It was followed by The River Between (1965) and A Grain of Wheat (1967), each work delving into the psychological scars of colonialism and the struggles of a people yearning for freedom.

These novels brought Ngũgĩ international acclaim. Yet even as he stood on the world stage, he grew increasingly uneasy with the limits of writing in a foreign tongue.

To him, language was not neutral, it was cultural, political, and historical. It held within it the power to shape how people saw themselves and the world.

And so, in one of the most significant decisions of his career, Ngũgĩ renounced writing in English altogether.

In choosing to write in Gikuyu, his mother tongue, Ngũgĩ ignited a fierce debate about the role of indigenous languages in African literature.

To him, the issue was clear: decolonization was incomplete unless it included the reclamation of language. His nonfiction work Decolonising the Mind (1986) became a seminal text in postcolonial studies, offering a searing indictment of cultural imperialism and a passionate argument for linguistic liberation.

A Literary Giant and Voice of Liberation- A Tribute to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o5

This commitment came at a great personal cost. In 1977, Ngũgĩ co-wrote Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”), a politically charged play performed by ordinary villagers in their own language.

The play’s bold critique of inequality and corruption infuriated the Kenyan authorities, and Ngũgĩ was arrested without trial. But even behind bars, his spirit remained unbroken.

In one of the most extraordinary acts of literary resistance, he wrote Devil on the Cross, entirely in Gikuyu on toilet paper smuggled out of his prison cell.

Upon his release, Ngũgĩ faced increasing hostility from the Kenyan regime, eventually going into self-imposed exile in the 1980s. From the United States, he continued to write, teach, and advocate for African cultural resurgence.

As a professor at institutions such as Yale and the University of California, Irvine, he became a mentor to a new generation of African and diaspora writers, encouraging them to draw strength from their roots and challenge dominant narratives.

Ngũgĩ’s bibliography grew to include not just fiction and drama, but essays, memoirs, and theoretical works that bridged literature, politics, and philosophy. His books, Petals of Blood, Matigari, Wrestling with the Devil, and Birth of a Dream Weaver, to name a few, blended revolutionary fervour with lyrical prose, always to awaken the African imagination.

He remained, until the end, a man of immense courage and conviction. Whether confronting dictators, Western publishers, or academic gatekeepers, Ngũgĩ stood firm in his belief that African stories told in African languages could transform the continent’s future. For him, literature was not a luxury, it was a necessity.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s passing is a monumental loss to the world of letters, but his influence endures in every reader stirred by his words, in every student empowered by his ideas, and in every storyteller who dares to write from the heart of their culture. He leaves behind a body of work that will long outlive him, books that are not just read but felt.

He challenged the world to respect Africa not just as a geographic space, but as a reservoir of wisdom, resilience, and creativity.

He called on Africans to believe in the legitimacy of their own narratives and to understand that the battle for freedom is fought as much through language and culture as it is through politics.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o may have laid down his pen, but his words remain etched in history, reminding us of the power of language to liberate minds and shape destinies.

Rest in power, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. You were the griot of our times, the rebel scholar, the eternal teacher. Your stories will continue to rise unbowed, unbroken, lighting the path for those who follow.

For More News And Analysis About Angola Follow Africa-Press