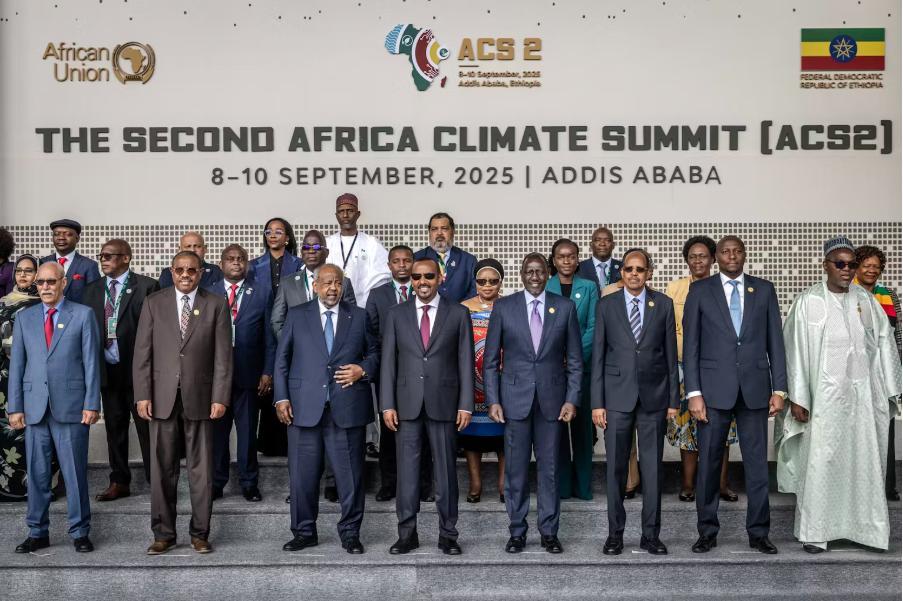

Africa-Press – Angola. The Second Africa Climate Summit, held in Ethiopia in September 2025, drew more than 25,000 people – from presidents and ministers to farmers, activists, business leaders and students. They came to talk about how Africa can source finance to grow in greener ways and cope with worsening climate disasters. Africa has barely contributed to greenhouse gas emissions but is highly exposed to climate-caused disasters. At the same time, the continent is not funded enough to adapt to the warming planet. Legal scholar Pedi Obani looks at the three biggest plans unveiled at the summit – and what it will take to turn them into reality.

Big finance for Africa’s green future

A major topic of discussion at the summit was how to increase the money available to fund Africa’s adaptation to the new, rapidly heating climate.

Climate change is already causing significant social and economic losses in African countries. However, only about US$195 billion will be made available by the international community to the continent for climate adaptation by 2035, far less than the estimated US$1.6 trillion required.

The summit featured some of the innovations that African countries are using to adapt to climate change and prevent climate disasters, and how to fund more of these. This was aimed at representing Africa beyond being a victim of climate change to a place housing leadership and solutions to global warming.

For example, Ethiopia’s Green Legacy Initiative has seen 48 billion trees planted in seven years. The Climate-Resilient Wheat Initiative, which aims to improve wheat production, productivity and the incomes of small-scale farmers, also featured, along with other green industries.

To speed up green industrialisation on the continent, African financial institutions such as the African Development Bank, Afreximbank, Africa50, Africa Finance Corporation, KCB Group, Equity Bank, Standard Bank Kenya, Ecobank and the African Continental Free Trade Area secretariat committed US$100 billion to the Africa Green Industrialisation Initiative (launched by the African Union in 2023 at the global COP28 climate change conference).

This initiative aims to accelerate green industrialisation in order to grow local eco-friendly industries, provide more employment opportunities, and make Africa a key player in the global green economy.

The summit also committed to funding 1,000 African climate innovations or adaptation projects every year. The Africa Climate Innovation Compact and the African Climate Facility will raise US$50 billion annually from now until 2030 to pay for these.

Countries also insisted that the global north should be legally obliged to contribute grants to Africa to fix climate-related damage. These grants must not require repayment, as loans make the already crippling debt burdens of African countries even worse.

A model climate law that African countries can adapt

Currently, around eight African countries have climate change laws in place. The African Group of Negotiators Experts Support, a think tank that provides governments on the continent with scientific and policy expert advice, presented a new Model Climate Change Law for Africa that was showcased at the summit.

This law can be adapted by African countries to suit their circumstances and include the international commitments they’ve made to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Having climate laws in place makes it easier for citizens to sue governments over climate disasters. It also benefits government agencies that want to enforce climate change obligations.

For example, in 2024, as many as 56% of climate cases in global south countries were led by governments. They aimed to make sure climate responsibilities were followed or to get compensation for climate-related damage.

The model law was co-created by parliamentarians, parliamentary staff, climate change experts and legal experts. When countries integrate their national circumstances into this law, this will be an important step forward in decolonising climate legislation globally. If more African countries have climate laws, this will amplify their voices in the global climate law landscape.

The model law also recognises that civil society groups of women, youth, Indigenous people and persons with disabilities should have some say in climate governance – not just governments.

Climate finance must be a legal obligation

Climate finance usually pays for activities or projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These include generating energy from clean or renewable sources and preserving forests that serve as natural carbon sinks. It also pays for support to people and ecosystems so that they can better adjust to any negative impacts of climate change.

Delegates at the summit said predictable, fair and equitable climate finance must flow to Africa as a legal obligation, and not as an option. They also proposed reforms of trade and investment frameworks to support economic and climate resilience.

The summit shows that there should be a diverse range of groups rethinking the climate finance system for justice. These must include indigenous communities, women, young people and faith organisations.

What needs to happen next

The summit held side events showcasing the contributions of civil society, faith-based organisations, women and youth groups. But most African countries are yet to include these groups in decision-making about climate adaptation. This must happen.

The world’s largest economies, the G20, currently led by South Africa, are not on track to being able to limit global average temperatures to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

The G20 accounts for around 80% of greenhouse gas emissions. Many of its members are increasing their production of oil and gas. This includes South Africa, the US, Russia, Canada and Saudi Arabia. G20 countries appear to be leaning towards carbon capture technologies and carbon trading markets rather than reducing their greenhouse gas emissions outright.

Therefore it was remarkable that African states broke with these practices at the summit. Instead, they committed to climate innovation, climate financing and enacting climate change laws.

The summit also showed that African countries are ready to lead the battle against global warming. Nigeria is already bidding to host the world’s annual climate change conference, COP32, in 2027. Ethiopia announced at the summit that it would put in a bid too.

Read more: Africa’s top climate change challenges: a fairer deal on phasing out fossil fuels and mobilising funds

However, the climate finance gap remains a problem. The 30th annual global climate change conference, COP30, in November 2025 will show how much international climate finance Africa is able to secure. COP30 will also likely try to make progress on setting up a loss and damage fund from which countries experiencing huge losses from climate disasters can claim damages.

Climate finance should create a fair space. It must be one where those most affected by climate change can take part in adapting to climate change, receive compensation for their losses, and see rules properly enforced.

theconversation

For More News And Analysis About Angola Follow Africa-Press