Africa-Press – Botswana. The High Court has explicitly established that the government bears a legal and moral obligation to provide life-saving medication and becomes liable when it fails to do so.

In a landmark judgment, the Gaborone High Court has ruled that it is not just a lapse in care but legal negligence when the government fails to provide essential medication.

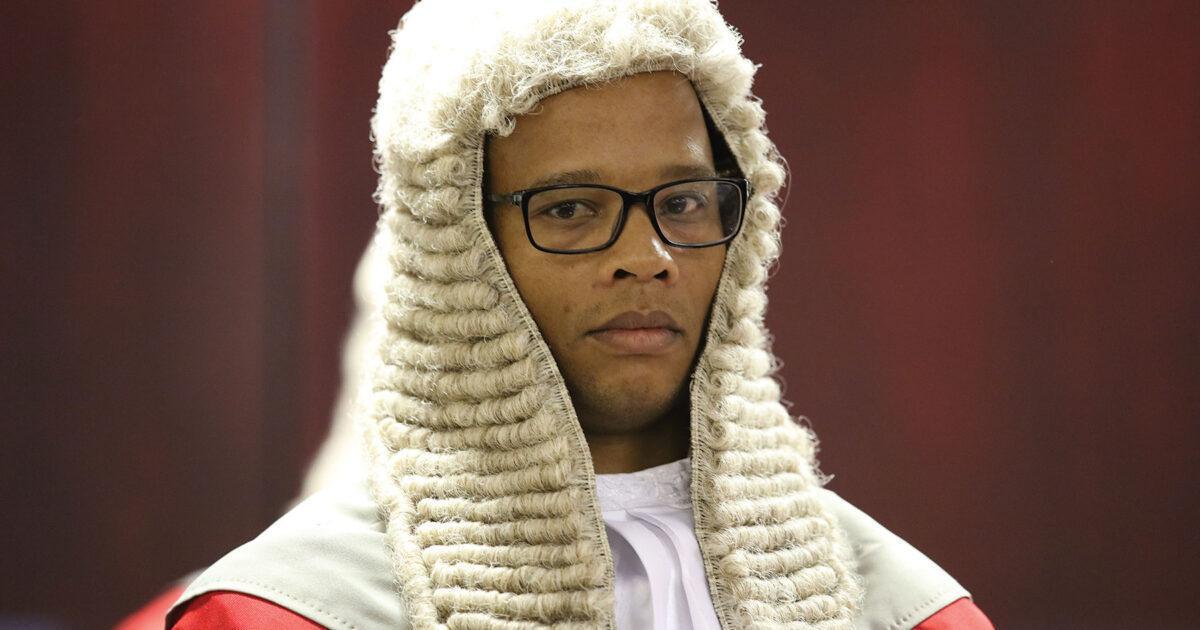

Justice Dr Zein Kebonang handed down the ruling in favour of Thandiwe Sibanda, a 31-year-old woman who suffered devastating emotional and psychological trauma after being denied timely access to post-rape treatment at public health facilities.

The judge awarded P200 000 to Zibanda as relief for her ordeal.

Sibanda had sued the government for P2 million in damages, along with interest and costs, for medical negligence stemming from the unavailability of essential post-rape care and medication.

Faulty results

Legal experts say this is a foundational judgment that opens the door for future litigation on the state’s obligations in public health service delivery.

According to the court record, Sibanda was brought by police to Nkoyaphiri Clinic in the early hours of 15 January 2017 after being raped the previous night. The attending doctor prescribed medication to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections but none was available at the clinic.

The next day, she sought the medication at Julia Molefe Clinic, which also did not provide full treatment – a lapse that later led to faulty results and delayed termination of pregnancy.

“Non-delegable duty”

In a damning critique of the state’s healthcare delivery system, Justice Kebonang ruled that the Ministry of Health (MoH), as the principal provider of public health services, had failed in its “non-delegable duty” to supply essential medicines, regardless of whether the failure stemmed from administrative, procurement, or logistical shortcomings.

“Ultimately, beyond buildings, infrastructure and equipment, a government elected by the people has both a moral and legal duty to provide life-saving medicine to all its people,” Kebonang asserted.

Basic demand

“It cannot avoid this obligation because with it, the people have entrusted the nation’s resources. It has no reason to fail in meeting this basic demand.”

In this the court articulated a legal doctrine that could set a precedent for future public health litigation:

“Although our Constitution does not confer a right to health care, in my view, as soon as the plaintiff was admitted and attended at the Ministry of Health’s hospitals/clinics, she was in effect accepted into the health system run by the Ministry of Health and therefore entered into a relationship with the ministry as a patient and the ministry as a ‘health care provider.’”

Patient-provider relationship

Justice Kebonang stressed that this patient-provider relationship imposed a duty of care on the ministry to ensure that prescribed medications were actually available.

He was unequivocal that the responsibility for providing medicine lies with MoH – not individual doctors or pharmacists – and that this duty cannot be outsourced or avoided under the guise of systemic failure.

“The systems failure argument, while I understand it, does not avail the ministry,” the judge ruled. “The res ipsa loquitur doctrine… allows a claimant to rely on the ‘thing itself’ to raise an inference of negligence… deduced by reference to ordinary human experience.

Since independence

“It is common cause that the ministry is the principal provider of public health services in Botswana. It assumed this responsibility since independence in 1966 and it can be said that it has a better appreciation of the risks of running hospitals or clinics without medication.

“Once the plaintiff was attended to or admitted into hospital, a relationship between the plaintiff and the ministry immediately arose. That relationship imposed a duty on the ministry to provide medication to the plaintiff and a class of persons in her position and protect her and them against a particular class of risks.”

Legal analysts say this doctrine, which has rarely been invoked successfully in Botswana, effectively shifts the burden of proof to the government, allowing victims of healthcare system failures to pursue claims without the burden of expert testimony.

Sibanda’s victory, though deeply personal, carries wide implications for a chronically strained health system long plagued by drug shortages, equipment breakdowns, and underfunding.

For More News And Analysis About Botswana Follow Africa-Press