Africa-Press – Eritrea. Multilingual and multicultural societies exist through their languages which transmit and preserve traditional knowledge and cultures in a sustainable way. Yet linguistic diversity is increasingly threatened as more and more languages disappear. There are around 6,500 languages in the world, and many are disappearing, with one language dying every two weeks. International Mother Language Day, which was celebrated in February under the theme “Fostering multilingualism for inclusion in education and society,” recognizes that languages and multilingualism can advance inclusion.

Many scholars and policy makers are becoming vocal that there are 50-75 million marginalized children who are not enrolled in school, and children whose primary language is not the language of instruction in school are more likely to drop out of school or fail in early grades. To solve this problem some countries have established language-in-education policies that embrace children’s first languages.

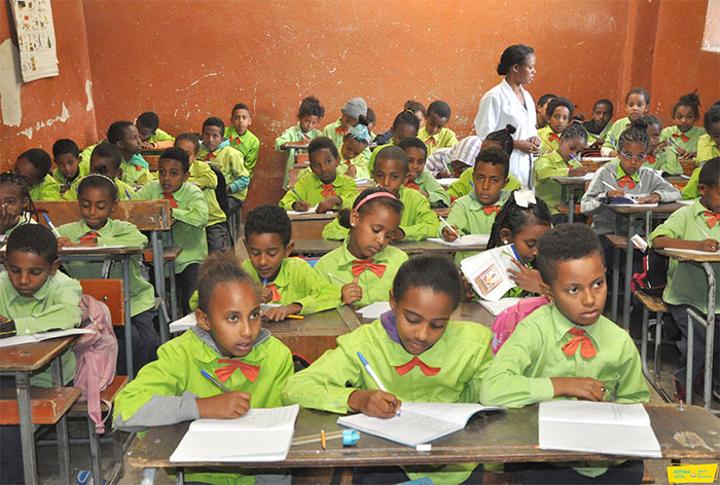

Eritrea clearly articulated in its national curriculum framework drafted in 2009 that basic education, which encompasses pre-school, elementary and middle school, is compulsory and children in pre-school and elementary must be taught in their mother tongue. Children with a strong foundation in their first language often display a deeper understanding of themselves and their place within society, and have increased sense of wellbeing and confidence. Naturally, this flows down into every aspect of their lives, including their academic achievement. Elementary level of education is a five-year cycle with the mother tongue as the medium of instruction and is viewed as an important formative period in the social, emotional and intellectual development of learners. The core learning areas provided at this level with mother tongue relatively weighting 22% are: mother tongue, English, mathematics, general science, social studies, citizenship, life skill, art and physical education. A collection of examples produced by UNESCO attests to growing interest in promoting mother tongue-based education, and to the wide variety of models, tools, and resources now being developed and piloted to promote learning programs in the mother tongue. Countries where the student’s first language is the language of instruction are likely to achieve the goals of Education for all. Recently. UNESCO has named Eritrea as a successful model for implementing a mother-tongue based and multilingual education (MTB-MLE) system.

The Ministry of Education (MoE) has stated that so much time and energy have been invested to coordinate a program of research that could advance knowledge on questions regarding the introduction of mother-tongue based education system. The questions relate to costs and benefits of alternative approaches directed at the individual, family, community, school, region, and nation; the implications of MTB-MLE for recruiting, educating, and mentoring teachers and teacher assistants and for creating and evaluating curricula in diverse language classrooms; the contributions of family and community in formal and non-formal MTB-MLE; and the effective approaches for successful transitions of mother-tongue educated children to junior school. The answers to these questions are still evolving. Nevertheless progress is being made in mother-tongue based multilingual education with a growing understanding of its importance, particularly in early schooling, and more commitment to its development in public life.

There are many reasons why MoE implements MTB-MLE. First, a child’s learning begins at home in the mother tongue and when a child comes to school to learn in a foreign language, it does slow down the learning process. Continuing the learning in the mother tongue will ensure faster learning and retention.

Second, exposure to more than one language leads to higher synaptic activity in the brain of a child and the multi-language processing leads to higher mental agility. This mental flexibility transfers to all areas of brain functioning.

Third, the use of the mother tongue as a medium of instruction will also result in a higher rate of parental participation in a child’s learning. Due to colonial education policies and cultural reasons, many Eritrean parents have not attended basic school levels and are unable to participate in their child’s schooling effectively.

Fourth, learning in the local language boosts the self-confidence of children and enables them to express themselves better without any hesitation. Mother tongue isn’t just a language but a sense of belonging for an individual. Learning in the local language helps to preserve our cultural roots and deepen our understanding of our heritage.

Fifth, with the use of local languages for learning, dropout rates can be dramatically reduced. A lot of students show disinterest to go to school because they are unable to connect with English and with no substitute coaching and lack of parent’s intervention, the odds are against them. But the use of a known language can dramatically alter the situation. Also, the switch to the local language will be a big advantage for teachers. One needs to have numerous and multiple opportunities to listen to and practice conversing in a language to become fluent in it. The interest, enthusiasm, and creativity of teachers is visible when they can teach in the local language.

Sixth, learning is always effective when it’s from the known to the unknown. With a strong foundation in the mother tongue or local language, a child can easily make a shift to learning another language.

Nelson Mandela once said, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head; if you talk to him in his language that goes to his heart.” Arguing with policy makers on the implementation of MTB-MLE puts everything at a stake: parents not enrolling their children in school at all, children not able to engage successfully in learning tasks, teachers feeling overwhelmed by children’s inability to participate, early experiences of school failure, and so on. Some children do succeed, perhaps through a language transition program that helps them to acquire the language of instruction. But there is the risk of negative effects whereby children fail to become linguistically competent members of their families and communities and lose the ability to connect with their cultural heritage. Increasingly, it leads to an inability to communicate about more than mundane matters with parents and grandparents, and a rapid depletion of the world’s repository of languages and dialects and the cultural knowledge that are carried through them.