Africa-Press – Eritrea. One of the main indicators of the development of a country is its human resource that makes up the workforce, and the productivity of the workforce, which is decisive to the advancement of a country, is realized through education. Singapore can be taken as an exemplary country whose development depends on its citizens’ education and its resultant innovation and creativity. Despite its lack in natural resources, the nation developed rapidly mainly because of its educated people.

Eritrea was under Italian colonization for fifty years. The colonizers might have built infrastructure, industries and commercial farms but did not develop the education sector. They followed a racial policy in education, allowing Eritreans to learn only up to grade four. This was done to distance them from development and enlightenment.

The Italians built the very first school for Eritreans in Anseba region. The school, built in 1908, was called Salvago Raji and was renamed Awald School and later Selam School. The school became the first official school built by the government and was the first to make it all the way until the British colonization. In his book “Eim,” which was written in 1893, the Italian author, Riffelo Perini, wrote that a school led by Catholic missionaries at Saint Michael in Keren and another one led by Swedish missionaries in Gheleb were serving local communities in the areas.

The school system in Eritrea changed during the British Administration. In the mid 1940’s access to education opened wide for those who had the will and desire to take lessons. Like people in other parts of Eritrea, the people of Zoba Anseba also had the opportunity to enjoy the taste of education. The Italian system that limited schooling to the fourth grade was replaced with one that allowed schooling at junior and high school levels.

A stable for horses and mules in Keren during the Italian rule was renovated and converted into a school, today’s Dearit Elementary School and Keren Junior School. The school which was opened in 1949 as Keren High School is the first high school in the Anseba region.

Until Eritrea’s independence in 1991, there were 30 government and private schools that hired 309 teachers and enrolled 20,020 students in Anseba region. In terms of gender, 106 teachers were women and 5469 students were girls. There was one secondary school- -Keren High School–with 1200 students and 12 Eritrean teachers, one of whom was a woman, and 18 expatriate teachers. Comparing the participation of female students before and after independence there is quite a gap. This is because before independence there was almost no participation but later on their participation leveled up because of the increase in education and enlightenment.

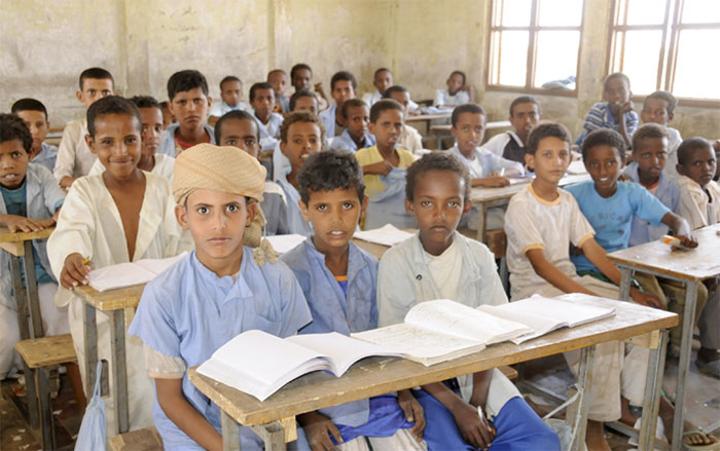

In the past 30 years there has been a dramatic change in all social services, education being one. In Anseba region, 310 schools (elementary schools and kindergartens) have been built in nine sub-zones that are staffed with 2156 teachers, 831 of whom are women. According to a report for 2020 and 2021, there are 7238 students enrolled at kindergartens, 50,610 in elementary and 24354 students in junior-high schools.

One of the biggest achievements in education in post-independence Eritrea has been the nationwide increase in the enrollment of girls. In the past few years 50,196 students have been able to sit for the Eighth Grade General National Examination in Anseba region. In terms of secondary schools, there are 18 schools operating in Anseba region. Nine of these schools are found in towns by the road side that stretches from Adi-Tekeliezan to Hagaz while the rest, including Asmat Boarding School, are found in sub-zones farther from the centers and the roads. Within the past 30 years, these high schools graduated 52,374 students, 19,914 of whom are girls. According to the region’s branch of the Ministry Of Education, most of the high school graduates joined colleges and vocational schools to attend degree, diploma and certificate programs.

In addition to providing formal education, Anseba region, like other regions, has been running an adult education program that aims to eradicate illiteracy and another program, “Aryet” (a Tigre word for ‘catching on’), targeting kids who were unable to start school at the right time. Most of these kids are unable to start school because they are married young or help out their parents in farming and raising animals. The program gives the kids an opportunity to catch on with their peers. According to the director for eradicating illiteracy, Abrhet Ghebre, “Aryet” has given justice to those kids from families of farmers and herders, and in the past 15 years, 28,663 kids have benefitted from the program.