Africa-Press – Eritrea. In our Eritrean culture, the rite of name- giving holds many significant honors. Beyond a sense of individual identity, it is often a reflection of family and the larger community. Names are tied to eras and hallmarks of Eritrea’s rich history and indicators of strong-rooted cultural beliefs, values, and norms. Names tell a story, hold memories, and are more than letters strung together.

With so many intersecting identities, such as ethnicity, religion, family practices, etc., there is no homogenous practice of naming a child amongst Eritrea’s nine ethnic groups, with as many languages, and a variety of religious practice from Christianity and Islam, to those that observe Traditional religions.

Generally speaking, religion and religious practices are deeply embedded in the daily life of Eritreans, and this is reflected through many names. Traditionally, stories in the Bible and Quran are excellent sources of inspiration for choosing a child’s name. While many names from both these Books are universal, the translation may result in a phonetically different sound in Christian names. For example, the name John in English will be Yohannes in Tigrinya, and the name David translates to Dawit. When names from the Bible are chosen, it is based on the person’s acts in the Bible rather than the meaning of the name. For example, according to the Bible, you will not find an Eritrean named Cain or Judas because of what their actions denote. It is also common for people to choose names of cities, landmarks, bodies of water, geographic locations, etc., that are in the Holy Books. Among the observers of Traditional religions, the naming of a child could be traditional deities or a name or a word they first hear during the birth of a child.

In the Christian lectionary, almost all the days are dedicated to an angel or saint. A child born on a day dedicated to a saint or angel is given a name with a prefix in conjunction with the name of the saint or angel. Some common prefixes are Welde (M), meaning “son of”; Gebre (M), meaning “servant”; Lete (F), meaning “daughter.” Using this method, the name Weldemichael translates to “the son of” Michael – which is the name of an angel. Likewise, Letemariam translates to “daughter of” Mariam – the name of a saint. Many of these names are given during baptism. While some use that name throughout their lives, others opt to use a different name. Interestingly, during rites of burial, a person’s baptismal name is the only name used. Positive or negative family circumstances can influence giving a name to a child during the time the child is born. Passing down the name of a deceased family member to honor the memory is standard. Only in rare cases is the name of a living family member given. It can be considered insulting because it insinuates a desire for someone to pass away to preserve their memory. Therefore, you will rarely see suffixes of “Jr.” or “Sr.” in Eritrean culture.

Among many communities, women reserve from saying the name of their father-in-law out loud. If a child is given the deceased grandfather’s name (and her father-in-law), the child’s mother will not directly call them by that name. Instead, she will often pick another name or use a nickname to address the child. For example, amongst Tigre speakers, many use “Gabsha” instead of “Ali” or “Reshid” instead of “Idris.”

Likewise, some women will not call their husbands by their first names. Instead, they will address them as “father of” and the name of the firstborn son or daughter.

When Eritrea faced a higher infant mortality rate decades ago, many believed the superstition that fairies would take children and were the cause of a child’s death. If a family experienced multiple child mortalities, they named the child an unconventional name in hopes that the fairy would not attract the child and spare their life. Examples of such names are:- Adgoy (donkey), Zboe (hyena), etc. Over time as the mortality rate decreased, this practice has also lost its predominance.

After independence, there was a notable change in choices of names. Many names expressing freedom (Natsinet), jubilation (Yohanna), etc., were given. Equally, names that reflect the struggle for independence were and remain popular – Nakfa – a town in Eritrea significant and momentous to gaining independence; and Salina – a place in Massawa where many Eritreans were martyred. Pre-independence, many children born in the diaspora were named Eritrea, honoring the desire for fruition for independence.

Generally speaking, most Eritreans are called by their first given names, and they don’t have a middle name. To address a person, you use the first name followed by the father’s name, and while in official documentation, the grandfather is added, this is not used as a “surname.” Contrary to many western practices, a married woman does not change her name as her identity is tied to her family of birth. Thus she keeps her father’s name.

There is much to be said and shared about how nuanced and interconnected to culture it is to name an Eritrean child.

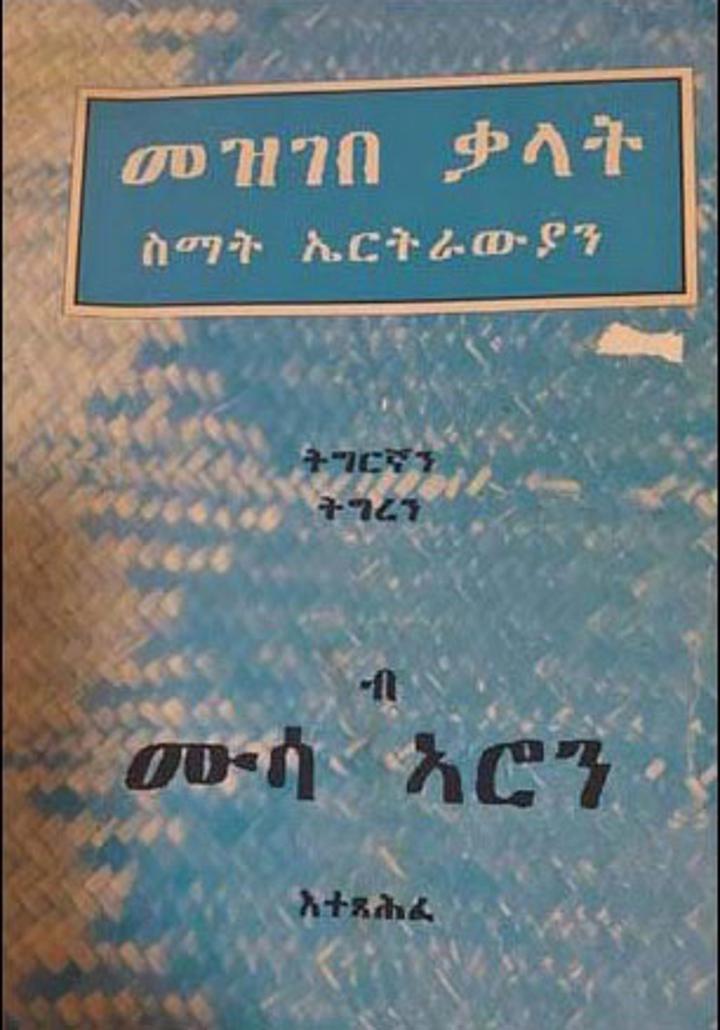

As generations of Eritreans are born, as culture evolves, and the Eritrean population in the diaspora grows, naming a child has become even more critical to preserve culture. However, as with many practices, passing on the stories, legacies, and knowledge continue to fall as the elders’ responsibility in the community. It is a great honor to be named “Rahel” by my father, who so diligently shared his wisdom and knowledge by authoring a Tigrinya dictionary of names. In carrying on his legacy and that of others who contribute to this intentional conversation, I say “: Every name is not built only by the sound of the alphabet, it has a meaning.”

Sources: Eritrean American Harmony Magazine Vol.1 No.1

For More News And Analysis About Eritrea Follow Africa-Press