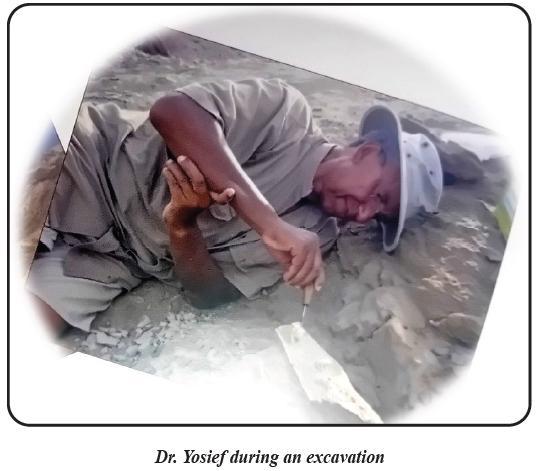

Africa-Press – Eritrea. The Eritrean National Museum was officially inaugurated in 1992 with the mission to preserve, study, and exhibit national history through valuable archaeological findings. Each year, the museum welcomes numerous local and foreign visitors, sharing Eritrea’s historical, cultural, and natural heritage. Today, we speak with the Director General of the National Museum, Dr. Yosief Libseqal. Dr. Yosief earned his first degree in history from Addis Ababa University, followed by a Master’s and PhD in historical archaeology from the University of Sorbonne Paris I in France. He previously served as head of the Department of Archaeology and as an assistant professor at the University of Asmara.

Dr. Yosief, could you begin by explaining what history is and its significance for humanity?

History is the study of the past through written records, which are compared, assessed for accuracy, placed in chronological order, and interpreted within the context of preceding, contemporary, and subsequent events. History helps people take pride in their culture, achievements, and future contributions. It also brings people together in peace and harmony by highlighting shared similarities rather than differences. A person who fails to understand history is destined to repeat past mistakes, while a society that ignores its history remains trapped in endless crises.

How would you define a museum?

Globally, there are several definitions of a museum. According to the International Council of Museums (ICOM), a museum is a permanent institution that conserves and displays collections of cultural or scientific significance for study, education, and enjoyment. While the museum is a Western institution, African museums should not simply copy this model—they should adapt it to their own environments. A building designed with traditional materials, for example, can blend seamlessly into its surroundings and reflect local heritage.

When was the National Museum established?

The Eritrean National Museum was officially inaugurated in 1992. It began through the efforts of a handful of artists from the revolutionary struggle and has since grown to include many young college graduates. The museum is organized chronologically, with sections covering Paleontology, Archaeology, Historical and Medieval periods, Ethnography, Colonial History, and a gallery dedicated to paintings of EPLF fighters from the long struggle for independence. Were there any local museums in Eritrea during the colonial period?

Before independence, there was no museum in Eritrea, and no site was listed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. For obvious reasons, the colonizers’ primary task was to marginalize and suppress Eritrean history and languages. When people lose their language, they lose their culture and national identity. Colonizers distorted Eritrean history through “documents” that justified conquest and suppression—a cancerous legacy of direct colonialism. After independence, rewriting Eritrean history becameimperative. Enriching and expanding the National Museum is part of this ongoing struggle to reclaim our national narrative.

What role does the Museum play in correcting distorted narratives of Eritrean history?

Although Eritrean archaeology’s full potential is not yet realized, initiatives are underway through the interpretation of excavated materials displayed here. One of our main objectives is to rectify and recuperate Eritrean history—especially ancient history—by studying dated artifacts, ethnographic materials, and oral histories. In short, researchers from the Museum, along with other experts, are striving to reconstruct an authentic Eritrean history based on scientific archaeological evidence. Political liberation has fostered a strong self-awareness and determination to do things the Eritrean way, but liberation from historical misrepresentation remains unfinished. Correctly interpreted and exhibited archaeological materials can help recuperate stolen legacies— histories that have been erased, marginalized, or misrepresented.

It should be noted that almost all historical periods are represented in Eritrea. To appreciate this richness, one should visit the National Museum and journey through successive eras, from past to present. Museums play a decisive role in interpreting history through formal education, using scientifically dated material culture.

How would you assess the Eritrean people’s awareness of the importance of preserving historical sites and artifacts?

Some experts claim that people living near archaeological sites feel no connection to them, but in Eritrea, the opposite is true. Eritreans have a deep emotional attachment to these sites, seeing them as part of their lives and protecting them from degradation. We’ve observed that communities even use these sites as respected spaces to resolve disputes. Even those living far away feel a sense of belonging. For example, an older woman from Mai-Temenai living abroad collaborated fully when workers digging a cistern on her property discovered archaeological materials dating to 400 BC. She was proud to have an archaeological site in her backyard.

Many objects—old swords, spears, shields, musical instruments, books, manuscripts, garments, coins, and photographs— have been donated by our communities. Additionally, farmers have willingly relocated when their land was identified as an archaeological site. These examples demonstrate the Eritrean people’s attachment to their past and their commitment to safeguarding their history.

How do you evaluate museum culture in Eritrea?

Honestly, despite our rich history, museum culture is not yet strongly appreciated in Eritrea. Consequently, the Museum is striving to cultivate it nationwide. We focus particularly on schoolchildren, as they are the future stakeholders of any museum. Once children develop a museum-going habit, others will follow. On average, about 800 students visit the Museum each week from central and other regions. Such visits are encouraging and testify to the relentless work of our curators, despite many challenges.

What reactions do you receive from foreign visitors?

Foreign visitors and tourists are often astonished and feel there is much more to discover about Eritrea’s distinct history, which dominant narratives have usually overshadowed. Visitors come from Italy, Germany, Sweden, the United States, and African countries like Chad, Cameroon, Sudan, and Kenya. They find the displays interesting and provide constructive feedback. African visitors, especially from Sudan and Egypt, appreciate connecting Eritrean archaeological displays with the broader context of African civilization.

Do you have any final message?

Last but not least, I would like to emphasize that “Eritrean history is as old as humanity itself.” I encourage parents to make an effort to bring their children to the Museum and to historical sites to connect them with the past and spark their imagination. Finally, I urge young people to keep exploring our national history armed with scientific evidence, to heroically win the struggle to liberate our history from distortion, misrepresentation, and marginalization.

Dr. Yosief, thank you for your time. We wish you great success in your future work.