Africa-Press – Gambia. Abstract

This study presents a perspective on how partnerships engaging private-sector actors could support greenhouse gas mitigation in African ruminant livestock value chains. Through using value chain governance theory and illustrative examples, we highlight potential contributions of these partnerships rather than demonstrate realised mitigation effectiveness. Using illustrative examples from beef cattle grazing, intensive dairy, and mohair fibre from several countries (South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda), we described partnership design. Across these illustrative examples, partnerships involving agribusiness companies and livestock producers linked low-emission practices to markets through quality-based milk pricing, village milk-collection hubs, the development of certification standards for mohair, and pilot programs in rangeland restoration and manure recycling. In some examples, public and nonprofit organisations helped finance embedded services (notably, grazing-plan support and milk-quality testing for price premiums) using buyer contributions, public budgets, or donor projects, including where livestock producers could not readily capture mitigation benefits.

Introduction

The objective of our study was to identify the conditions that enable or constrain partnerships engaging private-sector actors to support the uptake of practices that mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from ruminant livestock production in Africa. In this context, smallholder livestock producers are numerous and contribute to rural livelihoods, but they usually have weak bargaining power in value chains that are increasingly shaped by larger agribusiness companies. Given the limited verified evidence of private sector involvement, we used eight illustrative examples from East and Southern Africa to describe arrangements in operation, not to claim realised effectiveness. Our study is, in part, a perspective informed by these examples, value chain governance theory, and a framework on policy mechanism choice if agricultural decisions entail private and public net benefits.

Ruminant livestock producers in Africa that switch towards practices that reduce or sequester greenhouse gases often forgo private net benefits in the short run, because of initial costs and changes in management needed to provide better quality feed and grazing management1,2. In addition to forgoing economic benefits, the producers can generate social and environmental benefits. These benefits are typically not fully reflected in the market prices the producers receive as the benefits have aspects of public goods. Africa’s share of global net GHG emissions was 9% in 20193. Despite this small share, mitigation in Africa matters if it is low-cost, has mitigation-adaptation co-benefits, or is financed by emitters elsewhere through offsetting or insetting (funding emissions reductions within an agribusiness company’s own value chain). Examples of these co-benefits include vaccinations and deworming leading to reduced livestock abortions and calf mortality, which leads to increased meat production and lower GHG emission intensities4,5. Structural adjustment policies, including market liberalisation, have reduced public sector support for smallholder inputs, credit and marketing. However, increases in private sector investments beyond the farm gate to supply inputs and marketing services were slower than expected6. One contributing factor is high year-on-year variability in farmer income, linked to risk exposure and management7; this reduces the ability of the private sector to plan and limits investment incentives8.

GHG emissions from ruminant livestock are an important concern given projected increases in the demand for livestock products in Africa9, where livestock contribute substantially to livelihoods, nutrition, and employment in many African countries10. Globally, ruminant livestock contribute around 70% of livestock sector GHGs, which in turn account for about 12–20% of anthropogenic GHG emissions11—especially methane—posing a challenge for achieving climate goals. Reducing methane emissions from livestock is an important part of efforts to limit the increase in average global temperature to 1.5 °C (set under the 2015 Paris Agreement), requiring substantial cuts in GHG emissions by 2030 and 205012. Supplementary Note 1 provides further background details on this topic. Improving the sustainability of ruminant livestock production has received increased research attention, including through improved feeding and forages in East Africa13. While several animal-level GHG reduction practices are effective under experimental conditions, focusing solely on such practices does not directly consider value chain incentives and constraints. Other value chain participants—such as traders, processors, and input suppliers—often support smallholders through market access and increased productivity through offering services such as credit, inputs, extension, transport, and marketing. Yet, the role of these other participants in advancing environmental sustainability remains underexplored; notably, only 17 of 202 studies reviewed by Liverpool-Tasie et al.14 addressed this. A scoping review15 confirmed that despite private sector collaboration with farmers occurring in low-income countries, livestock and sustainability-focused partnerships are only a small subset of those collaborations. Market-based interventions have also been critiqued as being insufficient alone in some contexts to deliver environmental or equity outcomes for smallholder farmers because without public policies and safeguards, buyer–supplier power asymmetries can lead to unfavourable prices and a lack of access to buyers for smallholders16.

Our study focuses on existing market-based livestock value chains as market-based approaches are an important development pathway for resource-poor farmers14,17. We do not evaluate alternative approaches from an agri-food systems perspective, such as local food networks, participatory guarantee schemes, or urban farming. Studies on political agroecology and degrowth argue that these alternative approaches integrate food security with ecological sustainability to deconstruct market dependency and capitalist modernity, which value chain approaches may leave intact18,19. Nevertheless, investigating current value chain approaches under current market structures complements research on alternative approaches from an agri-food systems perspective. It should also be noted that amid the competing concerns of African farmers, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and policy makers, mitigation of GHG emissions, despite its global importance, is often only a conditional priority. Evidence from 38 interviews, including with staff from government ministries and research institutes, across Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia, suggests most actors prioritise adaptation20. They also favour integrating mitigation with adaptation by funding options that deliver both, rather than treating the two aims as competing, and emphasise the need for better measurement, reporting and verification systems for governments to be able to quantify mitigation.

Partnerships engaging private-sector actors often prioritise economic benefits, and without deliberate design and oversight, may overlook how smallholders can deliver public outcomes like lowering GHGs21. For example, in Kenya’s dairy sector, processors typically have prioritised supply and economic benefits, with smallholder GHG emissions intensity reduction becoming more of a focus through initiatives such as Kenya’s Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action for the dairy sector. The public and private sectors may also pursue different objectives—public sector actors often focus on addressing market failures like the under-provision of public goods, but some interventions also aim to develop sectors and raise producer economic returns. Private actors tend to prioritise economic benefits, especially in the absence of direct incentives for GHG mitigation. Tensions can arise between these objectives, for instance in nutrition-related programs, where a public sector objective is to alleviate malnutrition, some agribusiness companies have repeatedly breached the International Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes, undermining public-health goals and trust between the agribusiness companies, consumers, and the public sector22.

To address our study’s objective, we focus on three factors proposed to shape private-sector partnerships for GHG mitigation in African ruminant livestock value chains: (1) corporate governance and sustainability, (2) institutional support, and (3) buyer–supplier power asymmetries. We examine these three factors using eight illustrative examples analysed from a value chain economics and governance perspective.

Results and discussion

The choice of policy mechanism for GHG mitigation is often discussed in relation to private and public economic, social, and environmental outcomes. Many mitigation practices offer positive public, but negative private net benefits23, at least in the short run. In these cases, some of the mechanisms to enact change include technology development and the use of positive incentives24, such as payments for environmental services related to carbon pricing and carbon offset payments. However, such policies aiming to support lower GHG emissions in low- and middle-income countries are context-dependent, with transaction costs and scheme design influencing effectiveness and efficiency25. These limitations suggest that financial incentives should be complemented by non-financial institutional support, such as extension services for the use of GHG-reducing technologies.

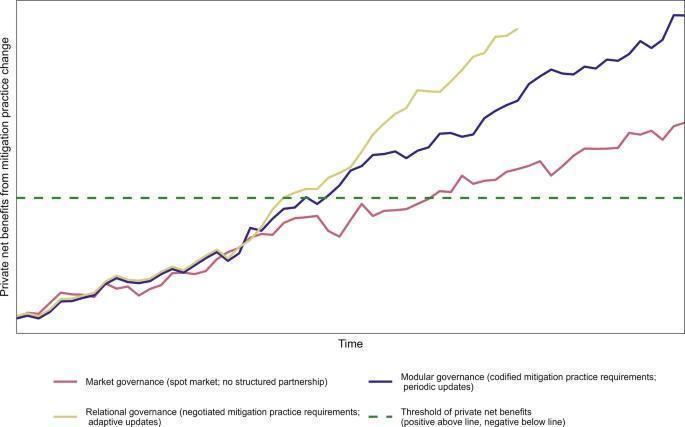

Figure 1 plots hypothetical private net benefits over time associated with a change in on-farm practice that lowers GHG emissions. When private net benefits are negative, the farmer incurs an opportunity cost from using a practice because alternative uses of their resources would generate higher private net benefits. The threshold level (dashed horizontal line in Fig. 1) represents the point at which private net benefits are zero and the farmer would be indifferent between changing their practices or not from a financial perspective alone. Private net benefits could include monthly cash flow for a commercial dairy producer or months of food security for a semi-subsistence pastoralist. However, over time, private net benefits may improve as producers learn to implement the practices more efficiently, gain better access to inputs through value chain improvements or policy support, and social contexts change (such as gender norms)26,27,28. In addition, over time environmental improvements, such as on-farm soil carbon increases, may also increase private benefits through improved productivity, while others, such as GHG mitigation, generate public benefits. However, negative short-term private net benefits detract from practice uptake, as economic benefits are a criterion for adoption and discount rates of future benefits are typically high in regions with uncertain economic outlooks28,29 (Supplementary Note 5).

Fig. 1: Conceptual illustration of how partnerships in value chains with different governance types can shift an African smallholder ruminant livestock producer’s private net benefits from adopting a GHG emissions mitigating practice over time.

The red, blue, and yellow lines show three commonly observed governance types from Table 1: Market, Modular, and Relational governance models. All trajectories are for the same mitigation practice, farm context, and product market; only the governance type varies. The solid lines show uncertainty in private net benefits over time (generated as Brownian motions), with values above the dashed line indicating positive private net benefits and below the dashed line indicating negative private net benefits. Time units are arbitrary. For visual clarity, the lines for the governance types are offset slightly on the y-axis and initially follow the same Brownian motion until the relational governance type diverges. Supplementary Note 6 provides the script used to generate this conceptual illustration. Source: authors’ elaboration.

In the conceptual illustration in Fig. 1, the time until expected private net benefits become non-negative (dashed horizontal line) is one possible factor influencing adoption rates. Different value chain governance designs could shift the trajectory of private net benefits, and, in principle, the time taken to become non-negative. Figure 1 compares three contrasting governance types. Under relational governance, actors adjust over time to changes in incentives, information, and coordination structures in response to adoption trends and contextual change such as public policies. The modular governance type coordinates through documented standards and revised terms less frequently, so producers could reach the threshold of positive net benefits after a longer period compared to the relational governance type. In Fig. 1, the relational and modular governance types could reach the threshold sooner than in the market governance type.

Conditions shaping partnerships engaging private-sector actors for GHG mitigation

We discuss three factors that have been proposed to enable the private sector to support GHG mitigation: (1) corporate governance and sustainability, (2) institutional support, and (3) buyer–supplier power asymmetries. We explore these factors through eight illustrative examples. Supplementary Note 7 discusses consumer demands as enabling conditions for private sector engagement.

Corporate governance and sustainability

Agribusiness companies in different segments of the value chain have adopted practices that aim to reduce or sequester GHGs, like carbon footprint accounting, and improved animal welfare standards. These companies often adopt these practices because of reputational concerns, investor pressure, or changing consumer preferences30,31. Also, these companies typically report these actions to the market through public briefs and to investors through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) or Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reports. These CSR and ESG reports can reflect a business’s awareness and actions towards improved environmental sustainability, but they do not replace institutional support: without farmer incentives GHG mitigation among African livestock producers, especially smallholders, would most likely be limited and hard to sustain. Agribusiness companies that market branded dairy or meat products are often positioned to partner with farmers to achieve positive private net benefits (dashed horizontal line in Fig. 1) sooner. These partnerships could offer farmers incentives like direct payments or product price premiums for practices that reduce or sequester GHGs; if animal numbers are held constant and the percentage reduction in lower emissions intensity is at least as large as the percentage increase in per-animal productivity, total emissions will not increase. But providing these incentives imposes a direct financial cost for the agribusiness company, which may limit uptake. This limited uptake is supported by Smith32, who noted ‘The ‘business case’ for investment in more sustainable supply chains is strongest if investment costs can be used to improve profitability by generating products with higher consumer value.’ CSR and ESG reporting can help justify these investments if they support product differentiation and higher consumer prices. In Rwanda’s speciality coffee sector, for example, smallholder growers receive only modest price premiums with most of the added value from higher export prices accruing with processors and exporters. Low farm-gate prices and farmers’ weak voice in price negotiations limit their ability to invest in productivity-enhancing labour and inputs33. So far, there is limited evidence of consumer willingness to pay price premiums for sustainability attributes in African livestock markets. In South Africa, 80% of surveyed beef consumers were unwilling to pay more for natural pasture-fed beef34, and only middle- and upper-class consumers showed some willingness to pay for low water or carbon footprint beef, with preferences that varied widely35.

Institutional support

In addition to economic concerns, perceived risks also constrain investments in GHG mitigation in the livestock sector, for example, in relation to incomplete property rights in rangelands36 and illustrated by the limited private sector engagement in initiatives to improve the measuring and monitoring of GHG emissions37. Partnerships between farmers and retailers only sometimes emerge spontaneously, which is one reason why public agencies, nonprofits, and international financiers like the World Bank have often supported initiatives that engage the private sector aimed at reducing on-farm GHG emissions. One example is the BioCarbon Fund Initiative for Sustainable Forest Landscapes administered by the World Bank. It offers results-based payments as an incentive to support the reduction of GHG emissions where investors—such as a donor government or agribusiness company with GHG emission reduction goals—pay a country, an agribusiness company, or community for achieving independently verified GHG emissions reduction targets. The payments support GHG emissions reduction goals while helping investors meet their own commitments under international agreements or corporate sustainability strategies. The World Bank manages donors’ funds (such as from the Government of the United Kingdom) to support the design and implementation of sustainable land-use programs. One example is the US$4 million grant supporting pilot activities for low-GHG emissions dairy development in Ethiopia38.

The Clean Development Mechanism, a United Nations-run carbon offset scheme, has typically attracted private sector investors in energy generation projects, with limited investment in agriculture due to challenges in capturing co-benefits privately36. While some voluntary carbon market schemes support agroforestry and livestock production39, they often prioritise systems with high economic benefits such as intensive dairy, where GHG emissions can be more easily reduced and measured. In contrast, pastoral systems are often considered institutionally complex and technically challenging for carbon schemes like the Clean Development Mechanism, due to limited options to reduce and accurately measure the GHG emissions39. Some tools exist to better estimate, measure, and monitor GHG emissions from livestock producers, notably the Cool Farm Tool that was commissioned by Unilever40, in addition to research tools like CLEANED41. Ecosystem service payments could, in principle, provide an incentive to improve grazing strategies by rewarding practices that maintain grassland health and sequester carbon. But these payments would be contingent upon credible institutions facilitating measurement and verification, and approaches for benefit sharing, as well as payments for those environmental benefits42.

Policy considerations are critical for providing the right incentives and enabling conditions for partnerships engaging private-sector actors. The mitigation of GHGs is often a stated policy priority for governments in Africa. It is widely acknowledged that some practices can lower GHG emissions and improve productivity, such as improved feed and livestock genetics42,43. Urea-molasses blocks for instance have the potential to reduce emission intensities by 6 to 27% and increase milk yield, depending on feed quality and breed used42. However, policies that are perceived to constrain agricultural productivity face substantial political resistance, especially given the widespread concern for household and national food security. In some low- and middle-income countries, historical policy choices, including trade distortions and underinvestment in agricultural research and development, have depressed price incentives for farmers44. Even in locations where supermarkets are becoming an important marketing channel, the ability for producers to obtain price premiums for sustainably produced products is often limited. This can be attributed to verification and regulatory barriers, which raise costs45 and to the persistence, for institutional reasons, of informal food value chains46. These reasons may include the coordination of product flows, access to relational finance and availability of affordable food under uncertainty.

Buyer–supplier power asymmetries

Buyer–supplier power asymmetries are a major concern in value chains governed by market-based coordination (Table 1) because pre- and post-farm private actors are increasingly consolidated and concentrated in some contexts, enabling agribusiness companies to set private standards in the sector47. This concentration in value chains can put farmers at a disadvantage when bargaining prices with more powerful farm input suppliers or if market-led approaches restrict farmer autonomy over what to produce and where to sell48. These power asymmetries can reduce farmers’ private net benefits and weaken their ability to use low-emissions practices.

The three factors of corporate governance and sustainability, institutional support, and buyer–supplier power asymmetries, discussed earlier, align with the findings of Mishra et al.15, who showed that private sector collaboration in value chains in low-income countries is influenced by private sector motives for market access and economic benefits, and for maintaining product quality. They also highlighted the importance of institutional support. Our study complements the work of Mishra et al.15, by focusing on African ruminant livestock systems, where the challenge of GHG mitigation is influenced by governance and market conditions. We applied a value chain governance perspective to identify when and how partnerships engaging private-sector actors can support GHG mitigation, and under what institutional conditions they are more likely to succeed. To understand when private sector actions could enable GHG reduction or sequestration on farms, we drew on insights from the general value chain governance and economics literature49,50.

Illustrative examples of partnerships engaging private-sector actors from a value chain economics and governance perspective

The reports examples from African ruminant livestock systems where the private sector is involved in emerging or potential partnerships with public and nonprofit actors. Value chain governance structures differ in buyer-supplier power asymmetries, coordination, and capability requirements. These features shape the prospects for GHG mitigation, as governance partnerships are often important for enabling mitigation efforts51. Using the examples in Table 2, we summarise the governance structure, coordination mechanisms, incentive structures, and the role of livestock producers, other private-sector actors (non-livestock producers), and public sector, along with potential positive outcomes and risks. The examples in Table 2 are taken from publicly available sources including organisational reports, websites (including media releases), and project documents (Supplementary Note 8, with a brief synopsis of each example in the Table 2 note). Most initiatives are recent or still underway, and in many cases, data on scale and effectiveness are limited or unavailable. Therefore, our assessment of the examples reflects the intended design and partnership models rather than verified impact for the initiative.Table 2 summarises eight illustrative examples and reports their value chain governance type, the main coordinating actors, the incentive mechanism, and the roles of livestock producers, other private-sector actors (including agribusiness companies), and government and NGOs, alongside potential benefits, risks, and partnership features. Most examples were classified as relational or modular value chain governance (often involving embedded services, training, or certification), with a smaller number classified as captive or hierarchy governance.

The examples suggest that the features of partnerships varied by governance type and the presence of institutional support. We grouped the examples by governance type and highlighted the conditions under which environmental objectives can be made attractive to agribusiness companies and other value chain participants.

In relational and modular governance models, such as the Sustainable Fibre Alliance or Dairy Nourishes Africa, partnerships can align climate goals with motivations of economic benefits for agribusiness companies —but typically require trust, certification schemes, or embedded services. In Dairy Nourishes Africa, the coordination of public nutrition objectives with commercial dairy market development is designed to support the adoption of climate-smart practices, enabled by trusted intermediaries. Gatsby Africa’s investment in Kenya’s ruminant livestock sector suggests approaches for philanthropic foundations and development financiers to play a role in coordinating structured value chains in feed, dairy, and meat processing.

In captive governance models like Brookside Dairy, the lead agribusiness company in the chain can enforce standards and provide embedded services, but these arrangements risk excluding smaller or less-resourced livestock producers unless inclusive upgrading strategies are adopted. In the Meat Naturally example (relational governance), Meat Naturally links livestock producers to buyers through mobile livestock auctions and mobile slaughter facilities, and provides training in rotational grazing and regenerative land management, aimed at lowering GHG emissions and restoring rangelands. The example also describes coordination with NGOs and embedded services as part of the arrangement. Nestlé’s Skimmelkrans pilot is a lead agribusiness company initiative, with a hierarchical governance type, to reduce GHG emissions through manure recycling, but its scalability will depend on continued investment and climate policy.

Across our illustrative examples, differences in the use of low-emission practices reflect both value chain governance52 and local feasibility conditions. For example, in Kenya, the uptake of low-emission dairy practices was higher in Murang’a than in Nandi and Bomet. This aligns with Murang’a’s more intensive zero-grazing context, which coincided with more manure collection, fodder growing, and full-time water access. In contrast, in non-zero-grazing systems (in Nandi and Bomet) manure management is labour-intensive, which constrains uptake. Livestock producers in Murang’a sold more milk to farmer cooperatives and processors, whereas in Nandi and Bomet they sold more milk directly to individual customers. Murang’a’s land pressure, proximity to Nairobi, and investments to formalise milk markets (through cooperatives) contributed to the dominance of zero-grazing53. In Tanzania’s dairy value chains, village hubs set up as part of a donor-funded multi-stakeholder project that brought farmers together with artificial insemination and input dealers (from the public and private sector) and traders, added milk quality checks, but milk output and marketing changed little because prices were low, inputs costly, and services unreliable54. A partnership in Nigeria between the Dutch agribusiness company Friesland Campina Wamco and the Nigerian government linked Fulani dairy cattle herders to formal buyers using milk collection centres55. However, these services may also create producer dependency if not designed equitably, as seen in Heifer International’s milk hubs, where farmers’ access to better prices depends on meeting quality standards. Outside Africa, India offers an illustrative example of an aggregation approach in which a large dairy cooperative is trialling feed changes with digital monitoring to reduce enteric methane emissions and test voluntary carbon revenue models.56

Public and nonprofit institutional capacity influences the potential for co-benefits from mitigation, such as improved incomes or rangeland restoration, and the ability to monitor and enforce sustainability standards. As noted by de Brauw and Bulte49, public and nonprofit institutions can help align private sector incentives with public sector goals such as GHG mitigation. In our illustrative examples, public sector support through financing or enabling policies often accompanies private sector actions to support the uptake of mitigation practices. Whether a partnership leads to widespread uptake of low-emission practices depends on the value chain governance, the distribution of costs and benefits, and the presence of public or NGO support to address capability, trust, and risk-sharing.

Table 3 links the examples to policy mechanisms, based on the balance of private and public net benefits using Pannell’s24 framework. The findings in Table 3 are illustrative; they reflect a qualitative assessment intended to inform future empirical research. Practices with high public net benefits but lower or negative private net benefits, such as rangeland restoration or carbon sequestration in extensive grazing systems align with the use of positive incentives to encourage adoption. Specific examples include the certification-based approach of the Sustainable Fibre Alliance and in the offset-based approach in the Northern Kenya Rangelands Carbon Project. Positive incentives, such as subsidies, are likely needed under current conditions to encourage practices that have proven mitigation potential such as those involving fodder trees and silvo-pastoral systems that sequester carbon57 and reduce reliance on low-quality grasses that contribute to higher methane emissions. However, in contexts with limited public-sector implementation and enforcement capacity, such as in some African livestock systems, the effectiveness of using positive incentives can be constrained58,59. If price incentives are strong, such as in dairy systems with quality-based pricing, extension services and common standards, such as milk quality testing protocols, could support market functioning (like Brookside Dairy). In cases with limited supplier capability to meet buyer requirements, uptake may depend on capability-building support and incentives conditional on independently verified outcomes. Because these requirements can be costly, they may shape who is ‘in’ and who is ‘out’ (for example, poorer or more remote livestock producers may be out), highlighting a role for capability-building support in reducing barriers to participation. An example of conditional incentives linked to verification is the use of participatory rangeland approaches with Kenyan pastoralists to co-develop grazing plans aimed at restoring degraded land, with payments only released if agreed rangeland condition indicators, such as ground cover, are independently verified60. Other examples such as forage technology development have demonstrated the potential of improved varieties of Desmodium spp. or Brachiaria spp. grasses to improve feed digestibility thereby lowering GHG emissions intensities, or the deep taproots of Brachiaria enhancing soil carbon sequestration61,62. Finally, if both public and private benefits appear substantial, as in Dairy Nourishes Africa or rotational grazing models like Meat Naturally, extension and embedded services may be the most effective and efficient mechanisms to promote further adoption.

In summary, we used value chain governance and policy mechanism frameworks to analyse when private-sector partnerships might support GHG mitigation in livestock value chains in Africa. From our illustrative examples, partnerships had the most potential when producers’ costs to use lower GHG emission practices were reduced through embedded farm services such as advice and training (Dairy Nourishes Africa in Tanzania and Meat Naturally in South Africa), input delivery such as forage seeds (Dairy Nourishes Africa), milk-quality testing (Brookside Dairy in Kenya), and grazing-plan support (Northern Kenya Rangelands Carbon Project and the Sustainable Fibre Alliance). Several illustrative examples specified who financed and ran these services, such as the buyer (Brookside Dairy), a project funder, or a public agency. Where expected benefits of GHG mitigation were mostly public goods and on-farm gains only modest, financing was sometimes public or by NGOs (Northern Kenya Rangelands Carbon Project). Buyer standards and product quality-linked premiums showed potential only if bundled with extension or embedded services and where a leading actor in the value chain was willing to finance the services or practice changes.

When public and private goals diverge, our illustrative examples suggest first identifying who bears the costs and who captures the benefits of shifting to lower GHG emissions, and then selecting an appropriate partnership arrangement. If mitigation benefits are mostly public, farm mitigation costs may be part-funded from public budgets or climate funds. If both sides gain but uptake is slow, extension and other embedded services that benefit the producer can be provided (such as Dairy Nourishes Africa or Brookside Dairy’s milk quality-linked services). If private actors benefit from practices that impose public costs (negative externalities), minimum standards with verification can help internalise those costs. Given the limited data and emerging role of the private sector in African livestock value chains, our conclusions draw these value chain design implications from our illustrative examples only. Further work is needed to quantify the impacts of the partnerships discussed in our study on productivity, livelihoods, and GHG emissions.Methods

Conditions shaping partnerships engaging private-sector actors

First, we present the conditions shaping partnerships engaging private-sector actors (and the public or NGO sector that enables them) for GHG mitigation: (1) corporate governance and sustainability, (2) institutional support, and (3) buyer–supplier power asymmetries.

Illustrative examples

Second, we identified specific examples of private sector involvement in GHG mitigation from documented examples in both public reports and the academic literature, and analysed them using value chain economics and governance frameworks. These examples were identified based on the authors’ networks and searching publicly available organisational reports and websites. These are illustrative examples; we do not claim they are demonstrations of proven efficacy. We distinguish two types of approaches to reduce or sequester GHGs from ruminant livestock production in Africa: (1) those that rely on improving the management of existing productive resources, and (2) those that result in external inputs. Supplementary Note 4 lists select on-farm practices within these two types of approaches.

Value chain governance

Third, we identified the type of value chain governance characterising each illustrative partnership that engages private-sector actors using the framework from Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon50. The framework defines five analytical types of value chain governance: market, modular, relational, captive, and hierarchy (Table 1). Three factors are used to determine the governance type: transaction complexity, ability to codify transactions, and the capability of suppliers meeting buyer requirements. Across the five analytical types, the degree of coordination and buyer–supplier power asymmetries depend on the joint effect of these three factors. Transaction complexity among chain participants reflects the amount of non-routine, interdependent coordination required for suppliers to meet buyer requirements. A complex transaction could be in a chain with relational governance where a processor and farmer group co-develop seasonal grazing plans as an approach to lower GHG emissions. Codifiability refers to how easily instructions can be specified and understood by others in the chain for product or process requirements. For example, the requirement that milk must be stored below 4 °C is easily codifiable, whereas the objective that cows should be sustainably fed on grass is not easily codifiable. The capability of suppliers to meet buyer requirements is the extent to which suppliers already have the skills, equipment and routines to deliver the buyer’s specifications consistently without intensive buyer support. For example, suppliers of small ruminants who have basic skills and equipment for vaccinating, tagging, and weighing animals could meet buyer specifications for animal health and traceability. Among the five governance types, market governance features an arm’s-length relationship between value chain participants, with price-based exchanges and where suppliers can easily switch among buyers63. In modular governance, capable suppliers deliver to codified specifications. Relational governance involves partnerships, often built on trust and learning. Captive governance has codified requirements but low supplier capability, and buyer power associated with switching costs. Hierarchy governance focuses on managerial control where activities are internalised within a business in the chain.

Fourth, we used principles from value chain economics and governance49,64,65 to assess how the examples supported or constrained the adoption of practices that reduce or sequester GHGs or promote land restoration. We align each example with a type of value chain governance, then describe the main coordinating participants, incentive mechanisms, role of public and private sectors, and potential benefits and risks.

Policy mechanisms

Fifth, for each example we identified a suggested class of policy mechanism from Pannell’s24 framework, which links policy mechanisms to the relative levels of private and public net benefits. The framework recommends: (a) positive incentives if private net benefits are negative, but public net benefits are positive (for example, financial or regulatory instruments such as subsidies), (b) communication and extension approaches if private and public net benefits are both positive (for example targeted education, technology promotion, demonstrations), (c) negative incentives if private net benefits are positive, but public net benefits are negative (for example, financial or regulatory instruments, including taxes), and (d) technology development if both private and public net benefits are negative (for example investments in research).

Supplementary Note 3 defines standard terms used in the current study. Notably, we treat livestock producers, including smallholders and pastoralists, as private-sector actors, and our study distinguishes two groups of private-sector actors: (1) livestock producers including smallholders, pastoralists, and all other producers of livestock products, (2) agribusiness companies, which include input suppliers, traders, processors, and downstream food companies.

nature.com