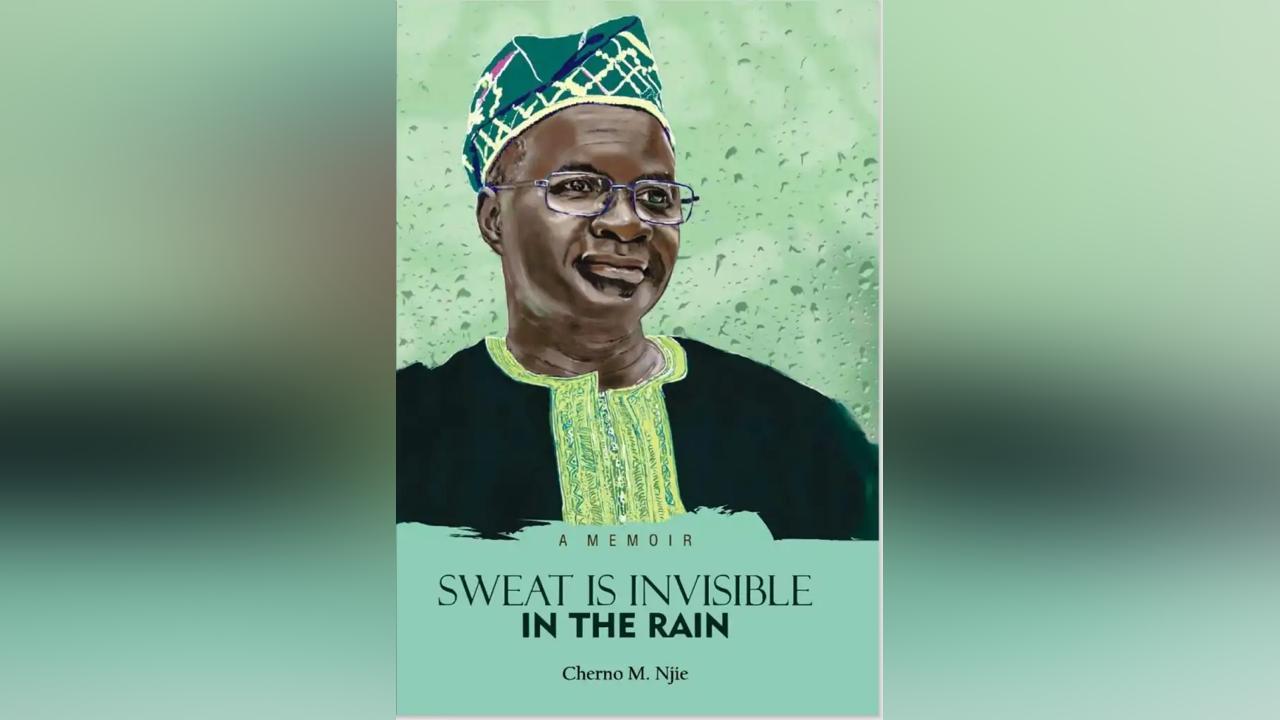

Africa-Press – Gambia. Cherno M Njie’s Sweat is Invisible in the Rain is a book that insists on being read both as an intimate memoir and as a political testimony. At over 300 pages, published by Pan-African University Press in 2020, it is a carefully woven account of childhood in Banjul, a life remade in the United States, and the author’s eventual involvement in one of the most dramatic episodes in recent Gambian history — the failed 30th December, 2014 coup attempt against Yahya Jammeh. It is the kind of book that refuses to confine itself to one genre: part family chronicle, part coming-of-age story, part political history, part prison memoir, and ultimately a reflection on what it means to carry the burdens of memory, duty, and exile.

Njie begins with memory. His recollections of Banjul are written in prose that is both affectionate and precise, conjuring the narrow streets, the crowded compounds, and the rhythm of daily life in the capital, which was once Bathurst under British rule and became Banjul after independence. The first chapters, grouped under the telling heading “Close Quarters,” evoke the world of extended family life, where a child was shaped not only by his parents but by uncles, aunts, cousins, neighbours, and elders. His father emerges as a central figure, a man who embodied both discipline and a quiet moral authority. At the same time, his mother anchored the household with the resilience that women so often contribute silently to African families. In these pages, the young Cherno Njie discovers the meaning of family, community, and identity, all of which would later serve as moral compass points when he would be forced to make grave choices.

The descriptions of school in Banjul are rich with detail: Wesley Primary School, Crab Island Secondary, the first encounters with teachers who commanded both fear and admiration, the youthful ambitions of boys who dreamt of succeeding beyond the confines of their small city. Njie’s early years of employment in banks — counting cash, learning the rudiments of finance, interacting with customers — reveal the hunger of a young man to be useful, to be productive, to carve out a life that was both respectable and promising. But there is also the quiet frustration of limitation, the knowledge that opportunities in The Gambia of the 1970s and early 1980s were narrow. It was this frustration, combined with ambition, that eventually propelled him towards education abroad.

When he crosses the Atlantic to study at Texas Tech and later the University of Texas at Austin, Njie narrates with honesty the disorientation of arrival, the cultural shocks, the sudden freedom, and the hard discipline of study. These years are written with both nostalgia and critical distance. They were the years in which he began to embody the duality of being Gambian and American, a citizen of two worlds. In Texas, Njie became a successful real estate developer and an engaged member of his community. Yet, success in America could never fully silence the voice of responsibility he felt towards his homeland. Like many in the diaspora, he discovered that exile is both a gift and a burden: a gift because it opens doors to education, resources, and stability, but a burden because one lives with the constant ache of distance, guilt, and longing.

The memoir shifts tone as it enters the era of Yahya Jammeh’s rule. Njie recounts with clarity how a country that had been a modest democracy under Dawda Jawara descended into fear and repression after the 1994 coup that brought Jammeh to power. He details the dismantling of institutions, the rise of the National Intelligence Agency, the terror of the Junglers, and the silencing of dissent. Gambians, once known for their openness, began to whisper in private, careful not to be overheard. The book does not sensationalise these years; rather, it records them with the sadness of someone who watched his homeland lose its innocence. Njie balances the narrative of fear with reflections on silence and complicity: why did so many Gambians remain quiet? Was it fear, pragmatism, or resignation? These questions haunt the book, giving it a moral texture.

It is within this climate that Njie and other Gambians abroad began to dream of resistance. The memoir gives detailed accounts of meetings among the diaspora, the debates, the frustrations with international institutions, and the anger that followed the rigged elections of 2011. At this stage, the prose acquires a sense of urgency. The author describes how the idea of confronting Jammeh militarily began to move from fantasy to plan. He does not embellish his own role, but he does not shy away from admitting that he was central to the financing and organisation of the plot. What is striking in these chapters is the balance between the idealism of men who felt they were doing the right thing and the sober awareness of the risks they were taking. Njie honours the memories of Colonel Lamin Sanneh, Capt. Njaga Jagne, and others who died in the attempt. He writes of them not as faceless conspirators, but as men with convictions, families, and dreams.

The account of the December 30th coup attempt is the memoir’s most dramatic section. Njie narrates the planning, the execution, and the failure with a storyteller’s gift for pacing. The assault on the State House, the confusion, the lack of coordination, the moments of bravery and miscalculation — all are rendered with a vividness that leaves the reader both enthralled and saddened. The reader senses that this was not merely a reckless adventure but a desperate attempt to liberate a nation. Yet, failure was swift and merciless. The men who fell are remembered with dignity, while those who survived were left with the heavy burden of explaining to the world why they risked everything.

Njie’s arrest in the United States under the Neutrality Act introduces another layer to the memoir. He writes with detail about the trial, the arguments presented in court, and the strange irony of being punished in America not for crimes committed there but for attempting to liberate his own country. His imprisonment in Beaumont prison is narrated with the same candour as his childhood stories. He does not wallow in self-pity; instead, he describes the routines of prison life, the fellow inmates, the unexpected solidarities, and the profound loneliness. These passages recall the prison writings of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in Detained or Wole Soyinka in The Man Died. What links them is the sense that prison, while intended to break men, can also sharpen their reflections on freedom, justice, and human dignity.

Perhaps the most poignant quality of the memoir is the way it weaves the personal with the historical. Njie inserts appendices that recount the colonial partition of Senegambia, the arbitrary borders drawn by Britain and France, and the resilience of Gambians who forged community despite external impositions. These sections remind the reader that the dilemmas of The Gambia today are rooted in deeper histories. He shows that dictatorship did not emerge from nowhere; it was nurtured by the fragility of institutions, the legacies of colonial rule, and the vulnerabilities of small states. By situating his own story within this broader canvas, Njie elevates the memoir from autobiography to history.

The title itself, Sweat is Invisible in the Rain, is deeply metaphorical. It suggests that struggle, sacrifice, and endurance often go unnoticed. In rain, one cannot distinguish between drops of water and beads of sweat, just as in the turbulence of dictatorship, the sacrifices of individuals are easily obscured. Yet, Njie insists that these sacrifices must be remembered. His memoir is thus both a personal record and a collective archive.

What makes the book compelling is its refusal to present a simplistic morality tale. Njie acknowledges doubts, admits mistakes, and reflects on the futility of violence. He does not glorify the coup attempt, nor does he denounce it entirely. Instead, he places it in the tragic context of a people who had lost all other avenues of change. This honesty makes the book trustworthy. The reader senses that this is not propaganda, but testimony.

The memoir’s style is deliberate and reflective, with long passages that move seamlessly between memory and analysis. Njie avoids rhetorical flourishes; his power lies in his restraint. The prose carries the rhythms of oral storytelling, enriched with proverbs and anecdotes. The narrative flow is steady, and while the book is dense, it is never dull.

In comparing Njie’s work with other African prison and political memoirs, one notices both resonance and distinction. Like Ngũgĩ and Soyinka, Njie writes from the experience of repression. But unlike them, his repression was not in Africa but in America, a reminder of the global reach of authoritarianism and the paradoxes of international law. Compared to Hassan Bubacar Jallow’s A Strange Destiny, Njie’s memoir is more raw, more intimate, less a chronicle of institutions than a confession of conscience. It stands in conversation with the writings of Baba Galleh Jallow on exile, dictatorship, and the moral obligations of intellectuals.

Ultimately, Sweat is Invisible in the Rain is a deeply Gambian story but with universal resonance. It speaks to anyone who has struggled with exile, anyone who has resisted dictatorship, anyone who has carried the burden of history. It is a book about courage and loss, about silence and speech, about the invisible sweat of sacrifice that rain cannot wash away.

Cherno M Njie has written not just his own story but part of the story of The Gambia. In doing so, he has provided future generations with a testimony of what it meant to live under Yahya Jammeh, to dream of change, to risk everything, and to reflect on failure. The book is long, layered, and demanding, but it rewards the patient reader with both knowledge and empathy. It is not simply a memoir — it is a moral document, a reminder that history is made not only by presidents and generals but also by ordinary men who refuse to be silent.

For More News And Analysis About Gambia Follow Africa-Press