By

Rishab Rathi

Africa-Press – Kenya. “The presence of mercenaries and other foreign fighters worsens conflict and threatens stability… Some mercenaries go from war to war, plying their deadly trade with enormous firepower, little accountability and a complete disregard for international humanitarian law.” remarked Antonio Guterres, United Nations Secretary-General.

Mercenaries have long shaped the course of warfare, from Pharaoh Ramses II reportedly employing over 10,000 mercenaries in the 13th century B.C. to Carthage in the 5th century B.C., which heavily relied on hired soldiers from Iberia, Gaul, and North Africa during its campaigns, particularly in Sicily. Throughout history, they played pivotal roles in major conflicts highlighting their enduring presence in global military history.

Mercenaries have played a major role in shaping Africa’s modern history, influencing events from the independence struggles of the 1960s to the conflicts of the 2020s. This article explores the role of mercenaries and private military contractors (PMCs) in contemporary African conflicts, highlighting their benefits, such as providing military expertise and flexibility, alongside the exploitation they often cause.

Background

Africa holds the second-highest number of armed conflicts worldwide, with more than 35 active non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) across various countries. These battles typically feature armed groups fighting against government forces or competing factions.

The use of mercenaries or private military contractors (PMCs) has seen a marked resurgence across Africa in recent years, driven by persistent conflicts and fragile state security. Libya alone has hosted an estimated 20,000 foreign fighters and mercenaries amid its protracted instability. In 2022, around 2,000 hired soldiers supported the Central African Republic’s armed forces. Similar patterns have emerged in countries like Mali, Mozambique, Sudan, and Burkina Faso.

During the decolonization period and the Cold War, mercenaries became institutionalized in Africa. Newly independent African nations were plagued by internal conflicts, prompting foreign powers to use mercenaries to support their interests. The CIA played a crucial role in supporting mercenaries during the Cold War, particularly in African conflicts. One notable example is the Congo Crisis (1961), where the CIA backed the infamous “5 Commando” mercenary unit. This unit was instrumental in supporting the secessionist Katanga province, which sought independence from the newly formed Republic of the Congo, and fought against the central government led by Patrice Lumumba’s successor, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, and his allies.

During the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), the CIA backed Holden Roberto and his FNLA forces in their fight against the Soviet-supported MPLA forces. As the revolutionary struggle evolved into a full-scale civil war, both the Soviet Union and the United States intensified their support for opposing factions, each seeking to shape the future of the newly independent nation. Despite growing public hesitation toward foreign interventions following the Vietnam War, the CIA remained committed to aiding the FNLA. The CIA’s covert hand was also evident in mercenary-led operations in Benin, Zaire, the Comoros, and the Seychelles. Conflicts often were orchestrated under the veil of “plausible deniability,” as Western intelligence agencies maneuvered to retain strategic access to Africa’s rich mineral resources and geopolitical influence.

Other countries, like France and Britain, played significant roles in the Nigerian Civil War (Biafra conflict of 1967–1970) through their support of opposing sides with mercenaries. French mercenaries supported the secessionist Republic of Biafra, while British mercenaries aligned with the federal government, highlighting the enduring Anglo–French geopolitical rivalry. These mercenaries, mostly pilots along with a few combat troops, had a limited strategic impact but notably influenced the dynamics of the conflict.

By the late 20th century, mercenary activity shifted toward corporate military contracting. Executive Outcomes, a private military company established by former officers of the South African Defence Force, emerged as a prominent example in this field. The company was involved in Angola and Sierra Leone, where it provided military support to governments in exchange for access to natural resources like diamonds and oil. This marked the transition from ad hoc mercenary forces to professionalized military companies offering security and combat services for financial gain.

The Russian Wagner Group has emerged as a major player across Africa. It has played a prominent role in the Central African Republic (CAR), intervening in support of the government and securing access to mineral resources in exchange for military assistance. In addition to Wagner, Rwandan special forces have been deployed to bolster government troops. The conflict in CAR remains deeply rooted in religious and communal divisions, primarily between anti-Balaka militias, composed largely of Christians, and ex-Séléka factions, made up of former Muslim rebels.

Operating in nations such as the Central African Republic, Libya, Sudan, and Mali, Wagner offers military assistance in return for lucrative mining concessions. Similarly, Turkish PMCs like Sadat have operated in West African nations such as Mali and Niger, aligning with Turkey’s growing geopolitical interests.

Current Operations

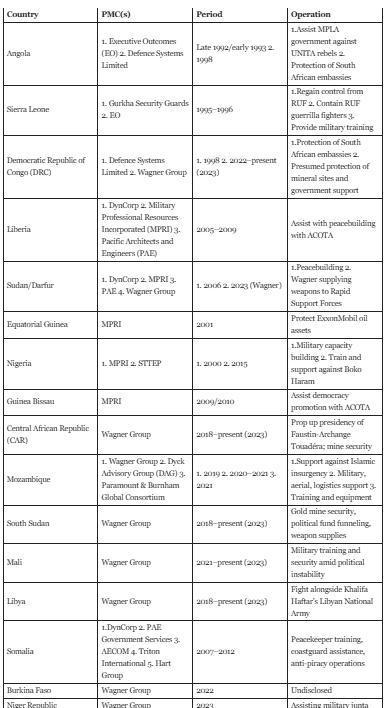

Data shows a high presence of the Wagner Group across major African conflicts, alongside other PMCs like Executive Outcomes, STTEP, and DAG.

It has become increasingly difficult to identify individual mercenary groups, as their informal command structures and overlapping operations blur clear distinctions. This lack of clarity is exacerbated by the absence of a unified international regulatory framework, which hampers efforts to ensure accountability and transparency in their operations.

Profiting from Chaos

Private military contractors have long blurred the line between state-sanctioned operations and mercenary profiteering, none more infamously than Blackwater. Founded by Erik Prince in 1997, Blackwater became the world’s most notorious private military company following the 2007 Nisour Square massacre in Baghdad, where its operatives killed 17 civilians. Though some personnel were later convicted, they were pardoned by U.S. President Donald Trump in 2020.

Other contractors, such as DynCorp International and Triple Canopy—both employed by the State Department—were not far behind, initiating fire in 62% and 83% of their escalation incidents, respectively. Blackwater, however, still recorded more shooting incidents than both combined.

Prince’s influence did not wane after Blackwater’s sale in 2010. He went on to launch several ventures, including the UAE-backed Reflex Responses and Frontier Services Group (FSG), which extended his reach into Africa and supported Chinese commercial interests. Despite FSG being sanctioned in 2023 for allegedly training Chinese military pilots, Prince re-emerged in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with a controversial 2025 deal to help tighten mineral taxation and reduce smuggling. Although his role was officially limited to logistics, the backdrop of earlier UN accusations—of planning to deploy thousands of Latin American mercenaries to secure mines in North Kivu—has reignited concerns over his real agenda in resource-rich but unstable regions.

The Wagner Group became Russia’s answer to the private military contractor model, emerging as a state-aligned paramilitary network along similar lines as Blackwater. Since deploying to the Central African Republic (CAR) in 2018, Wagner has entrenched itself deeply in the country’s mining sector, especially gold and diamonds, and expanded into timber. Midas Resources, a shell company linked to Wagner financier Yevgeny Prigozhin, leads operations at the Ndassima gold mine, where Wagner’s profits may reach up to $1 billion annually.

The group’s conduct in CAR, Mali, and Sudan has been marked by systematic human rights abuses—mass executions, sexual violence, and torture. Médecins Sans Frontières recorded over 19,500 cases of sexual violence in CAR between 2018 and 2022, while the UN documented nearly 15,000 more. In 2023, a report by The Sentry detailed how Wagner operatives not only looted civilian property but trained CAR forces in torture methods.

Similar brutality has been observed with the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), a South African PMC hired by the Mozambican government to combat the Islamist insurgency in Cabo Delgado. DAG operatives, using helicopters, were reported to have fired indiscriminately into crowds, dropped grenades on civilian zones, and destroyed critical infrastructure like hospitals and schools. Testimonies gathered by Amnesty International described scenes of chaos in Mocímboa de Praia in 2020, where helicopters “shot against everything and everyone.”

Strategic Advantages

Despite the violence and widespread abuses, Wagner was credited for repelling armed groups that threatened Bangui in 2021—underscoring the perverse duality of its role as both savior and aggressor. This reflects a broader trend across Africa, where states have increasingly turned to mercenaries and private military companies to confront security challenges beyond the capacity of their national forces, drawn by their rapid deployment, specialized skills, and politically convenient deniability.

Private Military Companies (PMCs) offer several advantages, making them increasingly appealing to states facing security challenges. One of the primary benefits is their rapid deployment capabilities and specialized expertise. For instance, in 2014, Nigeria contracted the South African company STTEP to help fight Boko Haram. STTEP implemented successful strategies, such as deploying Mi-24 Hind helicopters, leading to major territorial advances within a short time.

Similarly, the government of Mozambique hired both the Wagner Group and South Africa’s Dyck Advisory Group to fight Islamist insurgents in Cabo Delgado province. These forces provided not only direct combat support but also essential training and strategic planning, helping to fill gaps left by the national military’s limitations and contributing to the overall improvement of the national security apparatus.

Another key advantage of PMCs is their cost-effectiveness. In 1995, Executive Outcomes (EO) was contracted to remove Revolutionary United Front (RUF) forces that had seized control of key diamond mines in Sierra Leone. EO successfully achieved this objective and supported local militias, completing its operations over a period of 22 months at a cost of $35 million—more than one-third of the country’s annual military budget. In comparison, the United Nations Observer Force, which was deployed after the conflict, cost $47 million for just eight months, making EO significantly more cost-effective in direct military operations.

Compared to prolonged international peacekeeping missions, PMCs offer a more affordable and adaptable solution. Their services can be tailored to meet specific threats, making them particularly attractive to governments that require immediate results without the need for long-term commitments. Often, the process of involving mercenaries starts informally and is later formalized through contracts, which may include compensation in the form of resource concessions. In the Central African Republic, for instance, Wagner’s involvement was solidified through agreements granting them access to diamond and gold mines in exchange for military assistance, allowing the government to enhance its security without direct financial expenditure.

PMCs are also frequently employed to safeguard critical infrastructure and natural resources, ensuring political stability and regime protection.

Conclusion

The rise of private military companies in Africa stems from the intersection of fragile states, resource wealth, and foreign interests. While PMCs offer critical support, they often fuel violence and undermine sovereignty. As reliance on them grows, stronger international regulation will be essential to curb abuses and ensure they contribute to stability rather than deepen conflict.

moderndiplomacy

For More News And Analysis About Kenya Follow Africa-Press