WYCLIFFE MUGA

Africa-Press – Kenya. Not that long ago, I read of a senior public servant calling for a ban on politicians giving free “branded” exercise books to schoolchildren who were preparing to sit for a national exam.

By “branded”, I mean that a large photo of the generous donor was to be found printed on the back of the exercise books, and his or her name prominently included as well.

The idea behind this ban was that politicians should not use those schoolchildren as an access point to the voters, who were their parents.

But it must be borne in mind that this was all happening in a country where schools’ boards very regularly appeal to politicians to come to their school and help them to raise funds: for a new laboratory; for more classrooms; for replacement of a roof blown off by strong winds; etc.

And in any event, have we not in past years seen donations of cooking oil and foodstuffs, provided to the needy in parts of northern Kenya, bearing the large and colourful declaration “USAID: from the American people”?

Anyway, reading about this directive against donating free branded exercise books to schoolchildren, I remembered a story from some years ago; a story which taught me that it pays to be empirical in making judgements on the needs of other people.

This was back in the days of the 8-4-4 education system.

What happened is that a family friend of mine, tragically, lost a son who was only a teenager at that time.

And once the burial ceremonies were over, my friend approached me with a request for advice.

The family was not rich as such – no fleets of giant SUVs or helicopters – but they were determined to raise some money to create some kind of memorial to their son.

And what my friend wanted me to suggest to him was what sort of options there were for such activities, specifying that it had to be something that would benefit a good number of youths of approximately the same age as their late son.

I told him I would make inquiries. But also added that maybe they could consider the kinds of things politicians routinely did – as I noted earlier, contribute towards equipment for a new laboratory, or an additional classroom, etc.

But when I began on my inquiries – and made those inquiries on the pretext that I was looking for information and insights for an article I wished to write about the Kenyan education system – I got the surprise of my life.

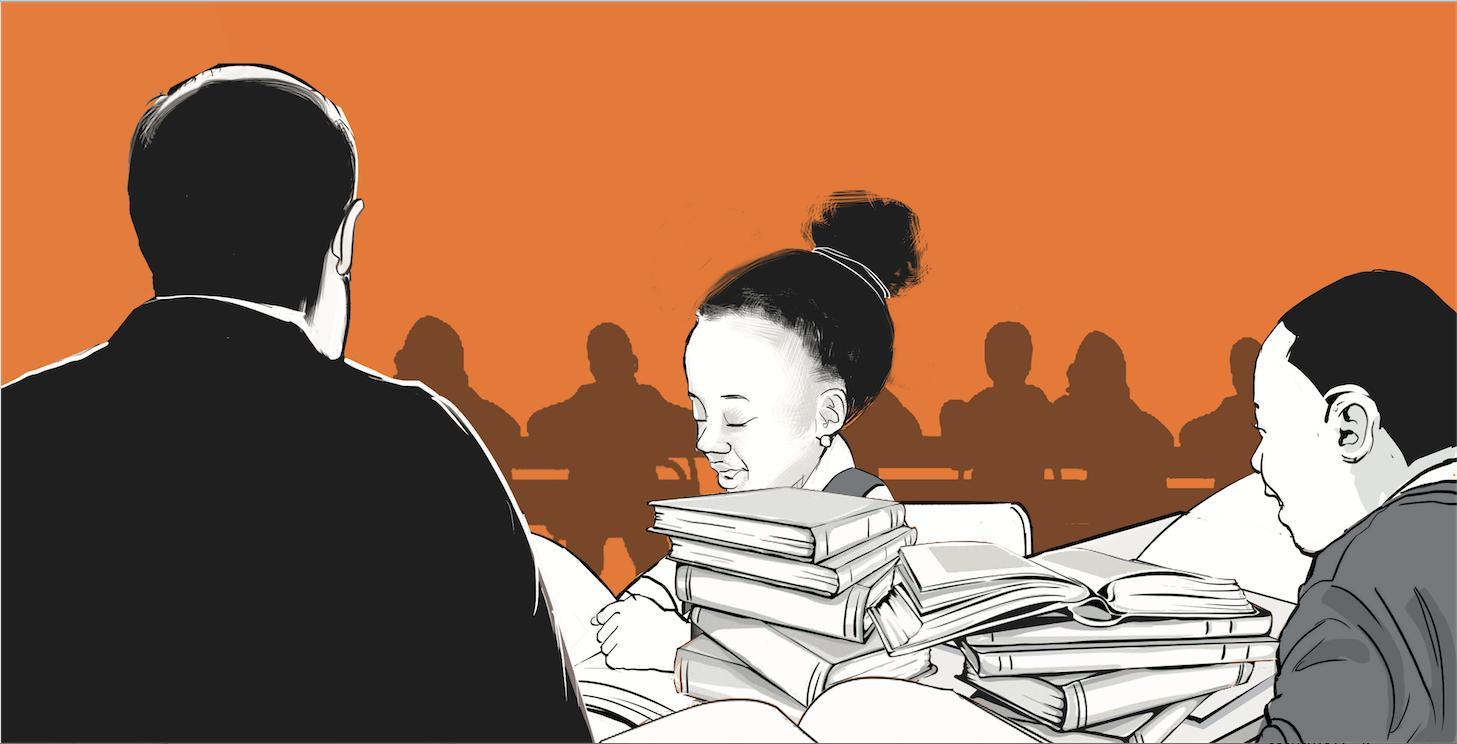

What the small sample of schools I approached wanted most of all was not for their classrooms’ earthen floor to be nicely cemented. Nor yet laboratory equipment. The teachers I spoke to were very clear that a major bottleneck to their students doing much better in national exams was that they needed more exercise books.

I had to pause and ask: “Did you say textbooks, or exercise books?” And the reply was, “Exercise books.”

And explanations followed.

Whereas their serious and hardworking students could mostly study using the textbooks that the schools provided, there were two crucial subjects which required unremitting practice using an exercise book. These were, first and more than anything else, mathematics. And then there was English and Kiswahili essays.

And as a writer I could easily appreciate that the only way you improve your writing – in whatever language – was by writing frequently and thus enhancing your ability to express yourself effectively.

As for mathematics, which I have never been particularly good at, I was willing to accept the opinions of the teachers I spoke to.

So, if the schoolchildren did not have to worry about running out of space in their exercise books; if they each got, say, five more square ruled exercise books, and five more single ruled exercise books; they would be able to do all kinds of additional schoolwork on their own to improve their performance in the exams.

The difference here then is that the view from what we may call the boardroom – the places where official policy is decided – was that politicians were “interfering” with schools when they went over and gave the kids those branded free exercise books,

While the view from what we may call “the ground” was that the more exercise books the kids had – no matter who provided them – the better they would be able to prepare for the national exams.

Source: The Star

For More News And Analysis About Kenya Follow Africa-Press