Africa-Press – Kenya. For years, Kenya and the United Arab Emirates(UAE) have signed trade deals promising jobs, markets for farmers and cheaper flights.

But many of those agreements have gathered dust.

Now, officials from both countries say it is time to “walk the talk,” raising a familiar question for ordinary Kenyans, will this finally mean jobs, better prices for farmers and more opportunities for youth, or is it just another meeting?

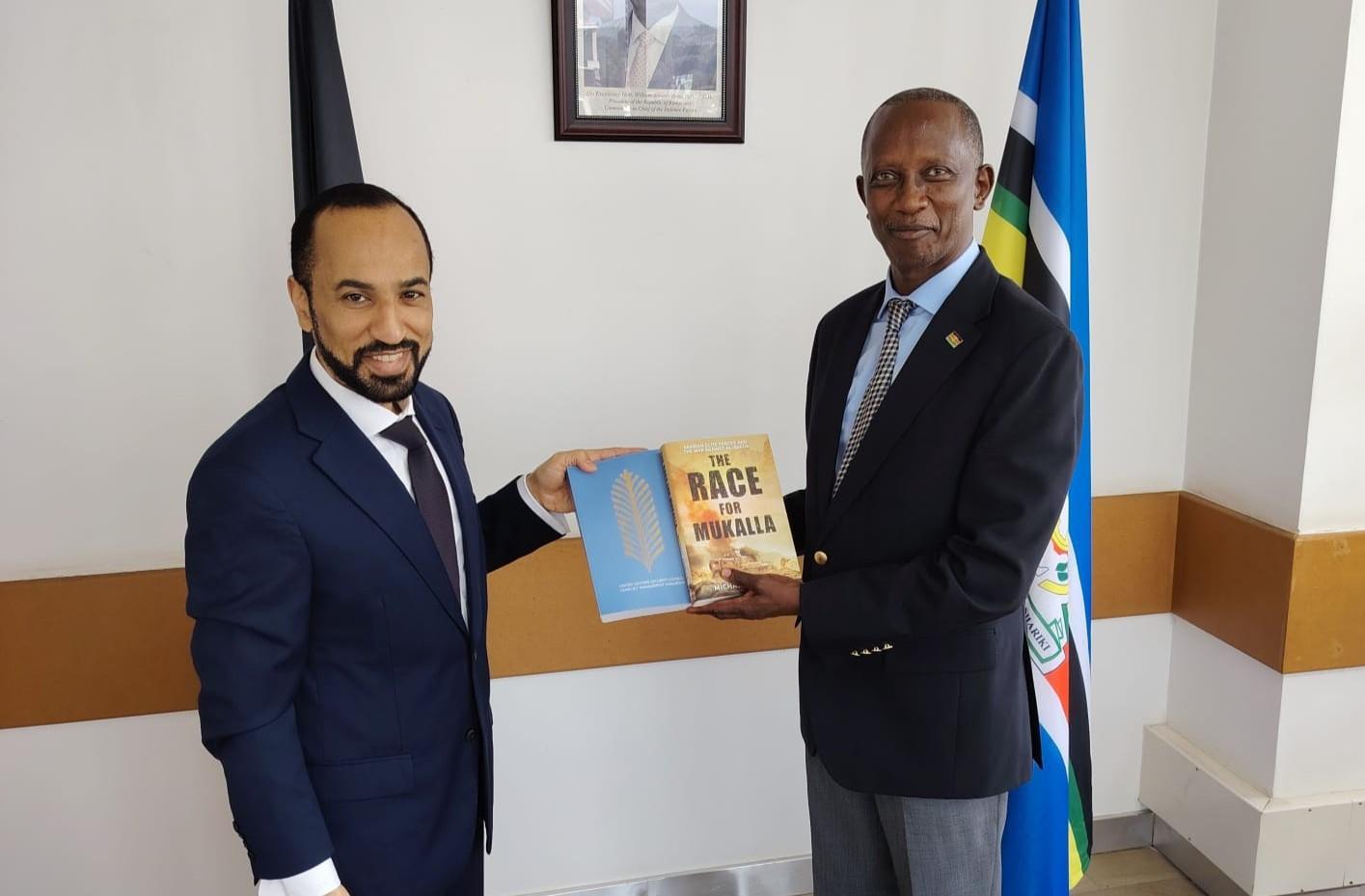

That question framed a courtesy meeting between Amb Lindsay Kiptiness, Deputy Director General in Kenya’s Middle East Directorate, and Salim Ibrahim Alnaqbi, the Ambassador of the United Arab Emirates, as the two sides reviewed bilateral relations and assessed the implementation of agreements signed over recent years.

At the centre of the discussions was the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), a flagship trade deal signed and ratified by both countries in January 2025.

While the agreement is intended to deepen economic ties and unlock new opportunities, officials on both sides acknowledged that progress in implementing CEPA and other concluded memoranda of understanding has been slow an unusually frank admission that echoes public frustration with deals that rarely move beyond paper.

Against this backdrop, the two sides agreed on the need to “walk the talk,” shifting focus away from announcing new commitments to delivering tangible results, particularly in trade, investment, and economic cooperation.

For farmers and exporters, CEPA carries the promise of improved access to the UAE market for fresh agricultural produce such as fruits, vegetables, flowers and meat.

In theory, the deal should ease customs procedures and reduce trade barriers, allowing Kenyan produce to reach high-value Gulf markets more efficiently.

In practice, many small-scale farmers continue to face high logistics costs, limited export information and the dominance of middlemen, raising concerns that the benefits may remain concentrated among large players.

Labour mobility was another key issue discussed, resonating strongly in a country where youth unemployment remains a pressing challenge.

Expanded labour cooperation with the UAE could open employment opportunities for Kenyans abroad, but it also revives long-standing concerns around worker protection, fair contracts and the treatment of migrant labour issues that will test how people-centred the partnership becomes.

Air connectivity and tourism were similarly highlighted as areas with direct impact on everyday livelihoods.

Improved flight links could lower travel costs, stimulate tourism, and strengthen business ties between the two countries.

For hotels, tour operators, transport providers and small businesses across the tourism value chain, this could mean increased activity if commitments translate into action.

The meeting also explored cooperation in infrastructure, technology, research and human capital development, alongside exchange programmes for young diplomats and knowledge sharing.

While such initiatives promise long-term gains, their impact often takes time to filter down to households and small enterprises.

Senior officials from Kenya’s Middle East Directorate and representatives of the UAE Embassy attended the meeting, signalling engagement at a level capable of influencing policy direction.

The emphasis, however, was clear: credibility will now be judged less by who attends meetings and more by what changes on the ground.

Trade between Kenya and the UAE has grown steadily over the past decade, more than doubling in value as the Gulf state emerged as one of Kenya’s most significant trading partners.

Kenya’s exports to the UAE have largely comprised agricultural products, while imports have been dominated by petroleum products, machinery, electronics, and vehicles.

Much of this growth, however, has been organic, driven by market demand rather than the direct impact of formal trade frameworks, reinforcing scepticism over whether recent agreements will meaningfully change conditions for small exporters and traders.

Kenya and the UAE also maintain cooperation in the energy sector, including fuel supply arrangements that have helped stabilise imports during periods of economic pressure.

While such agreements rarely dominate public discourse, their impact on fuel availability and price stability has been among the more tangible outcomes of bilateral engagement.

Beyond economics, the two ambassadors reaffirmed their commitment to supporting peace and security efforts in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East, noting that stability is a prerequisite for economic growth.

Without peace, they observed, trade stalls, investment retreats, and job creation suffer.

While the renewed tone and acknowledgement of past inaction suggest a shift, many Kenyans remain cautious.

For farmers seeking fair markets, youth searching for jobs, and businesses weighed down by high costs, the true measure of the Kenyan UAE partnership will not be future meetings or carefully worded communiqués, but tangible outcomes felt beyond boardrooms and briefing rooms.

Until then, the call to “walk the talk” will remain not a promise, but a test.