By Nic Cheeseman

Africa-Press – Lesotho. She felt that it was not just “The Arch” that the country had lost in 2021, but its sense of unity and purpose. After the unrest that followed the arrest of ex-President Jacob Zuma in July, and the failure of the African National Congress to win a majority of the vote for the first time since the end of apartheid in the November municipal elections, the future appeared worryingly uncertain.

The next twelve months would play a pivotal role, she felt, in deciding whether “what didn’t kill South Africa will make her stronger” – or would lead to a further process of institutional decay.

A few days later, a Kenyan friend wrote in response to the deaths of former attorney general Charles Njonjo and conservationist and one-time head of the Kenya Wildlife Service, Richard Leakey.

Neither Leakey nor Njonjo was revered in the way Tutu was, but their loss in quick succession still led him to feel that it was the “end of an (already bygone) era”.

Viewing the early years of the Kenyan one-party state through somewhat rose-tinted glasses, he bemoaned the extent of corruption and ethnic politicking on display among the political class – and feared that given recent economic difficulties the upcoming general election could harden both ethnic and class divides.

These conversations got me thinking about the trajectory of Africa’s more influential countries, and the impact it will have on the rest of the continent. Will the most powerful states pull those around them down into deeper difficulties? Or lead a much needed economic and democratic revival?

Around the time I was having these discussions about Kenya and South Africa, I edited an essay about the conflict in Ethiopia, which also depicted a country at the crossroads. It argued that recent developments, including the advances by Ethiopian government forces, had opened up the opportunity for peace talks.

But a decisive move towards a negotiated settlement has yet to materialise, despite a recent conversation between United States President Joe Biden and Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed – and if the warring parties seek to enforce an outright military victory, conflict will continue well into 2022.

It is not just Kenya, South Africa and Ethiopia that are living in “interesting times”. At a meeting I attended in mid-December, a similar concern was raised about the prospects for stability and order in Nigeria.

Rising insecurity has leant increasing credence to the argument that the country is a failed state, with the government unable to protect its citizens in the most basic ways.

Against this backdrop, controversy around elections scheduled for February 2023 could have far-reaching implications not just for voter turnout but for the legitimacy of the political system more broadly.

This raises an important question: does it matter for other African countries if Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa are all experiencing difficulties? All countries are impacted by what happens to other states in their region, especially those with which they share a border.

This is particularly true of regional hegemons that, through their greater economic power, military might, and/or political influence are able to shape the fortunes of other countries.

The expansion of a region’s biggest economy creates more opportunities for trade and hence for economic growth and job creation – even in a context in which economies are not heavily integrated. A politically stable country whose government is keen to promote democracy and the rule of law can also foster a better governed neighbourhood.

Conversely, civil conflict in a hegemon generates negative externalities such as outflows of refugees and the disruption of trading networks and regional travel routes, which can be especially problematic for landlocked states.

As a driving force within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Nigeria has also been influential in promoting democratic norms abroad – even as it has infringed on them at home.

. The major worry for Africa as is that all of its hegemons face challenging times.

South Africa is the dominant economic player in southern Africa, with a gross domestic product (GDP) more than five times the next largest economy in the Southern African Development Community.

South African companies such as Shoprite and Mr Price have networks – most prominently through a series of identikit malls – across Malawi, Zambia and beyond. Especially in smaller countries such as eSwatini and Lesotho, South Africa also exerts considerable political influence.

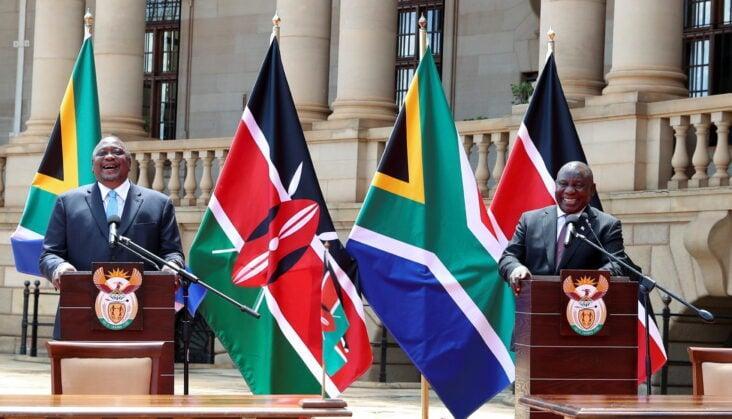

Should he wish to, President Cyril Ramaphosa can encourage or block democratic change – as demonstrated by the way that Thabo Mbeki pursued “quiet diplomacy” in Zimbabwe, and in the process insulated Robert Mugabe from Western pressure for political reform. Nigeria plays a similar role in West Africa, with a GDP more than six times larger than the next biggest economy.

As a driving force within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Nigeria has also been influential in promoting democratic norms abroad – even as it has infringed on them at home – such as when ECOWAS troops played a central role in forcing Gambian dictator Yahya Jammeh from power in 2016.

East Africa doesn’t have a hegemon in the same way – there is no one country that exerts such an outsized influence on the others – but for different reasons Kenya and Ethiopia exert a considerable pull over political and economic affairs.

These are the two largest economies in the region, and while Kenya is an important access point for both goods and people, Ethiopia borders more Eastern African countries (six) than any other state.

If these countries struggle in 2022, it will be that much harder for their neighbours to thrive. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that Kenyan economic growth will expand to 6% in 2022.

Elsewhere, however, the forecast is more troubling: South African growth is expected to fall from 5% in 2021 to 2.2% in 2022, and Nigeria is projected to flatline at 2.7%.

The situation in Ethiopia is unclear, as having previously been bullish about the prospects for recovery, the IMF declined to release a forecast in October – a measure usually reserved for “failed states”.

Cyril Ramaphosa is unlikely to become more pro-active about solving political crises in eSwatini and Zimbabwe while he has his own to defuse back home. Such projections are not always accurate, of course.

They may prove to be too conservative if careful political stewardship goes hand-in-hand with good harvests and rising tourism, but they may also understate the potential for another difficult year.

As professor Karuti Kanyinga has argued, in election years in Kenya spending goes up as politicians lavish money on voters, but investment and growth stagnate due to concerns about the risk of political instability.

This effect was less pronounced in recent elections, but could return if the expected contest between Raila Odinga and William Ruto is close and conflictual. Nigerian growth will also be undermined if banditry continues to drive population displacement and the disruption of economic activity.

Meanwhile, South Africa may struggle to hit 2.2% if Covid-19 continues to undermine international travel – especially if further bouts of civil unrest disrupt economic activity.

In addition to hampering regional trade, another year of hegemonic instability would undermine the inclination and ability of powerful governments to play a constructive regional role.

Cyril Ramaphosa is unlikely to become more pro-active about solving political crises in eSwatini and Zimbabwe while he has his own to defuse back home.

Similarly, Nigerian efforts to combat terrorist activity in West Africa will be compromised if the security forces cannot get domestic criminality under control. It is therefore in the interests of many African states that these “hegemons” have a good year.

https://www.theafricareport.com/168249/africa-in-2022-the-danger-of-hegemonic-instability/

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press