Africa-Press – Lesotho. By Romain Gras

How are American lobbying firms chosen? Why are they so often solicited? From Brian Ballard to Joseph Szlavik, do these costly intermediaries obtain concrete results?

We investigated lobbyists used by the continent’s political elite who try to influence US policy, uncovering an opaque and lucrative world where making a real impact is the stuff of fantasy.

While Liberia, Morocco, South Africa, Egypt, and the DRC are particularly fond of these firms, almost every country on the continent uses their services.

The Homer Building, located on 13th Street in downtown Washington, is an architectural anomaly. Hidden behind a rather mundane 12-storey exterior is the original building, built in 1913.

It is wrapped in a four-storey mix of historic and modern structures in marble, metal, and gilding that over the years has housed various government agencies, diplomatic offices and law firms over the years.

The Homer Building, which over time has become a centre of power and influence, located just three blocks from the White House, had all the makings of an attractive location for Brian Ballard to establish the first Washington office of his lobbying firm, Ballard Partners, on the second floor.

With a tanned complexion and a tailored suit, this elegant 50-year-old is first and foremost a familiar face among Florida’s Republican elite. For 30 years, he has made himself known to the successive governors of what is known as the Sunshine State.

A close ally to Jeb Bush, brother of former US President George W. Bush, a regular at the Mar-a-Lago residence, the luxurious property of billionaire Donald Trump, Ballard has, for more than three decades, learned to dine and play golf with all the powerful people of this southeastern state.

Since President Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, Ballard Partners has been steadily expanding its African client base. As is often the case on K Street, the avenue that has earned the city its reputation as the capital of influence, and the numbers are dizzying.

Ballard’s October 2017 contract, which he signed with former DRC Katanga governor Moïse Katumbi is $50,000 (FC103m) per month. Katumbi was a presidential candidate during the 2018 DRC presidential election and hired Ballard personally.

This is double the value of another contract signed in July 2018, between the Florida firm and the Malian authorities, who were then seeking additional support in their fight against terrorism.

Since March 2022, Ballard Partners has been advocating on behalf of a new client: the DRC, currently being led by President Felix Tshisekedi, at a premium cost of $900,000 per year.

The Florida firm’s apparent success is not an isolated affair. In Washington, pro-African lobbying is a business that continues to flourish. Corridor diplomacy has its codes and foreign governments have long accepted the rules, the often-high cost, and the transparency requirements.

Since the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, lobbyists recruited by foreign agents have been required by US law to declare their activities to the Department of Justice.

Although it remains a minority of the turnover of the city’s main firms, African clients – both governmental and non-governmental – generate several tens of millions of dollars in contracts each year.

Between 2016 and 2020, more than $161m was spent at various firms, according to a January 2022 report by the Centre for International Policy. More than two-thirds of that amount came from just five countries: Liberia, Morocco, South Africa, Egypt, and the DRC, according to the same study.

Every country in Africa has a vested interest in seeing its interests well-represented on the other side of the Atlantic. But what is the ever-increasing number of clients seeking the services of these lobbying firms? On K Street, lawyers, spin doctors, former senators, and diplomats have clear access to the federal government, and opportunities to intervene in certain media, or before think tanks.

Above all, they market their contacts. Each firm has its narratives, its key lobbyists, and its political contacts on both sides of the aisle. “Lobbying, like a lawyer’s job, is about presenting a credible case to decision-makers based on evidence and what we believe to be factual information,” explained Sylvester Lukis, one of the Florida firm’s lobbyists.

“The US is a very difficult machine to move and it is often complicated for diplomats here to get the right access,” says a Washington-based lobbyist who has worked for several countries, including the DRC, in a field he describes as private diplomacy.

“But we should not make a caricature of this. The lobbyist is not there to sell wind. ”

“80% of the time, lobbyists are doing the job that an embassy should be doing,” says former Undersecretary of State for African Affairs Tibor Nagy.

As the State Department’s ‘Mr Africa’ for the duration of the Trump presidency, the diplomat, who held several ambassadorial posts on the continent, was a prime target for lobbying firms active with African clients.

But he now tends to downplay their impact. “When I meet with leaders, no lobbyists are invited,” he says. Very often, these firms have functioned as a means for their clients to navigate a complex American political administration, itself a sprawling system with multiple poles of influence.

“Just because you have access to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, it doesn’t mean that the entire Congress is behind you.

Just because you’ve seen someone on the National Security Council, which reports to the White House, doesn’t mean the State Department necessarily agrees.

For example, during the 2018 presidential election in the DRC, the two entities were not in sync on what to do after the presidential results,” says the anonymous lobbyist quoted above.

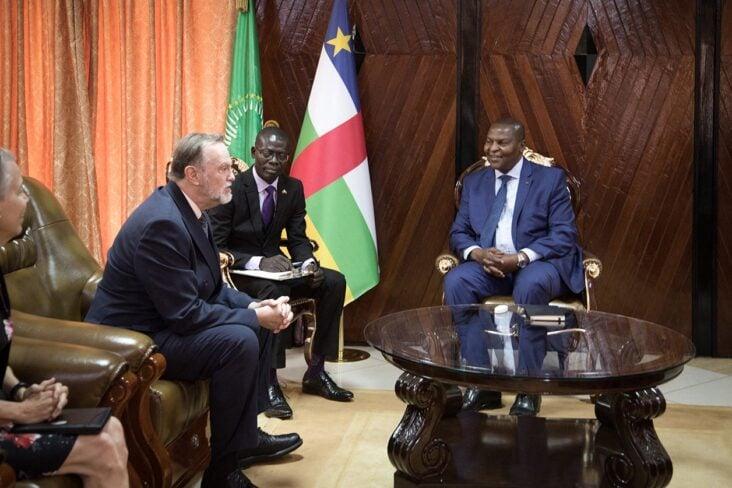

The US-Africa summit, organised by President Biden from 13 to 15 December 2022, served as an opportunity for many of the delegations present to again demonstrate their collective interest in these costly intermediaries.

Although the American president was careful to exclude only Eritrea and the countries suspended from the African Union (Sudan, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea), some of the guests came to Washington under a certain amount of pressure. This was notably the case of Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno.

Questioned by the State Department after the announcement of the postponement of elections and repression of demonstrations, including in front of the US embassy, the man known as Kaka approached, via his half-brother Abdelkrim, the firm Yorktown Solution, one of the many lobbyists who work with Morocco in Washington.

The Chadian government’s move was primarily a way to respond to the recent overtures made by its main opponent, Succès Masra, who had been, for several weeks, attempting to make contact with Congress and the State Department.

Prior to the summit, he was able to secure a meeting with Molly Phee, Undersecretary of State for African Affairs. Today, Washington is now a theatre of lobbying competition in its own right, with the prize being the prioritisation of many of the continent’s issues.

Morocco, for example, spends more than $1m each year to advance its position on several bilateral issues, but also on the thorny issue of Western Sahara, exporting its rivalry with Algiers to the US capital.

Rabat, one of K Street’s main clients, has secured the services of at least four other firms, including Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld and Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, which are among Washington’s biggest influencers.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press