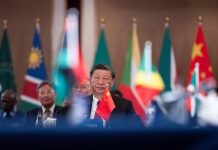

Africa-Press – Lesotho. IN September more than 50 African leaders trooped to Beijing for the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) summit, a jamboree where China showcases its warm relations with Africa.

A red carpet was rolled out for the leaders, including Lesotho’s Prime Minister Thomas Thabane. And amid pomp and funfair Chinese President, Xi Jinping, dangled the dollars to the mesmerized leaders, most of who were there for donations and soft loans.

Some were jostling to lure Chinese investors to their countries and open new markets for businesses back home. President Xi promised Africa a mouthwatering US$60 billion in financial support and assistance.

Of that amount US$20 billion will flow into the African continent in new loans. Xi also pledged to open up the Chinese market to the African manufacturers.

As if taking cue from the government, the China’s largely nobbled media was at pains to promote the summit as a sign that Beijing is engaging Africa as an equal partner.

In one of the many glowing stories on the summit Xinhuanet, a government controlled news agency, quoted one Zeng Aiping, whom it called an expert in Sino-African relations, waxing lyrical about China’s relations with Africa.

“Some western countries impose certain conditions to support the Africans,” said Zeng, as if reading passages straight from the Chinese government’s strategy notes on relations with Africa.

“But China only pays attention on economic development to invest in the continent and that, in turn, will serve public interest and humanity as a whole,” Zeng said. Back home, Thabane seemed delighted by the goodies China had promised at the summit.

He told a press conference that China has sent him back home him with a fat kitty of M300 million in cash donation, M50 million worth of rice and M16 million in food aid.

China, Thabane said, had cancelled Lesotho’s debt for the construction of the parliament and ‘Manthabiseng Convention Centre. If you count what he had brought from China it sure sounded like this had been a fabulous trip.

There was much to celebrate in the relationship with the Chinese. But as he was crowing about the FOCAC summit something ominous was happening in Teyateyaneng, a small town some 40km from the capital. There, a group of workers in tatters were off-loading cow manure on land now controlled by a Chinese agriculture company.

Basotho Farming, as the company is curiously named, has bought and leased huge tracts of land from locals, most of whom had stopped farming after it dawned on them that they had neither the skill nor the financial muscle to compete with the Chinese.

In 2016 Basotho Farming was a single greenhouse perched on the edge of Teyateyaneng River. Barely three years later it’s a sprawling complex of more than 350 greenhouses standing on prime land either bought or leased from local farmers.

Those who refused to let go of their land have their fields marooned in the complex of greenhouses. To get to them they have to go round the greenhouses that now house potatoes, tomatoes and cabbages belonging to a consortium of six Chinese businessmen.

Now instead of working their land some of the farmers are now workers on the farm. They earn about M2000 per month, according to those workers who could mumble some answers in between their chores.

And the Chinese keep coming for more land to expand the farm that now straddles both sides of the river. They have built a rickety footbridge for workers to cross to the other parts of the farm.

Soon they might have to build another one to reach other fields whose owners are on the verge of capitulating to pressure to sell or rent out. The manure that five of the 50-odd workers at the farm are offloading has been bought from local farmers who, under normal circumstances, would have used it to nourish their tiring soils.

In surrounding villages farmers have swept every morsel of dung to make a quick buck from the Chinese farmers who are more than willing to buy. The local farmers who used to buy manure from other locals cannot match the prices paid by the newcomers.

When the Chinese first came to the valley local farmers felt curious rather than threatened. It was just one greenhouse manned by foreigners who did not speak the local language.

A few locals got casual jobs at the farm. The locals continued to use their fields for maize during the wet seasons and vegetables when the rains were gone.

Cabbages and potatoes were their crops of choice. They would draw water from Teyateyaneng River using buckets and wheelbarrows. The vegetables provided income to send children to school and feed their families during the dry seasons.

The market for the cabbages and potatoes was mostly fellow villagers and a few people in Teyateyaneng town. They would harvest their cabbages before dawn and carry them on scotch-carts or hired trucks to get to town before the sun comes up.

Their market was on the streets but there were those who had enough capital to supply supermarkets in Teyateyaneng, Leribe, Maseru, Maputsoe and Butha Buthe.

That market however started drying up as the Chinese produced more and slashed the prices. Squeezed out of supermarkets, the locals resorted to the streets.

There was no way the farmers could compete with the Chinese. Where their cabbages were at the mercy of weather elements those of the Chinese were in greenhouses with controlled climate.

When the farmers were using tins to water their crops the Chinese were using drip irrigation with water from a deep borehole. The Chinese had imported tractors from China and locals were using draught power.

When it came to planting potatoes the locals would use hoes while their neighbours had planters. Locals also used hoes to dig up their potatoes while the Chinese had harvesters.

The Chinese have even brought their pesticides, fertilizers and seeds from home. The playing field was thus steeply tilted in favour of the newcomers in terms of manpower, skills, capital and equipment.

And soon the Chinese had the best land too as some farmers quickly surrendered their fields for either a once off payment or an annual fee. In just three years the Chinese taken over the tomato, cabbage and potato market in the area.

Tolley Chen, a bubbly manager at Basotho Farming, says business is good. “We are happy because there is a prospect that it could grow bigger,” Tolley says in fluent Sesotho.

The ambition, he says, is to supply the whole country with tomatoes, potatoes and cabbages. So far they supply Teyateyaneng, Leribe, Butha- Buthe, Maseru and Mafeteng.

Tolley will not say who owns the farm and how much has been invested in the project. “I am just a manager here. ”

He also doesn’t want to say how many Chinese work on the farm.

Apart from Tolley there are two more Chinese men on site today. One is working with locals to fix a malfunctioning potato planter. The other is giving orders to workers harvesting cabbages.

In an hour a truck full of cabbages from the farm will be parked at a shop in Teyateyaneng. Another will be near the bus station to sell the cabbages directly to the customers.

The Chinese sell each cabbage for M4, whether you buy in from the farm or their truck in town. Local farmers, on the other hand, say they need at least M8 to make a small profit and leave enough to put more seed in the ground.

But that is not going to happen because price is king and the Chinese now call the shots in this market. They have a superior product in abundance. The local farmer has been pushed out of the wholesale, retail and informal markets.

The liberalist view is that local farmers should toughen up and fight the Chinese on the market. They should use new production methods and be willing to invest more capital into their projects, so goes the logic.

But that doesn’t work in a country where locals don’t have the means to become commercial farmers. Farmers in Teyateyaneng know that trying to compete with the Chinese is like taking a knife to a gun fight.

It’s a battle they have tried to fight but lost dismally. Ask the Tsikoane sisters who have two greenhouses up the road from the Chinese. In 2015 the sisters got M290 000 from the Smallholder Agriculture Development Programme (SADP) under the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security.

The programme’s mission was to improve food production in rural areas, create employment and empower communities. The sisters spent M178 000 of the grant to build the greenhouses while the remainder was used to drill a borehole as well as buy a water tank, irrigation equipment and some seed.

The sisters thought they had a fair chance of competing in the market until their borehole dried up during winter, forcing them to use 20-litre containers to get water from the communal tap in the village.

This year is particularly bad because their cabbages had have wilted due to lack of water. Only 1300 of the 5400 they planted have survived. And even those remaining are so shriveled and so tinny that they would not fetch as little as M3 on the market.

The locals who used to buy from them are going to the Chinese. Again, price and quality are the driving forces. “They used to buy a lot but now they don’t,” says 32-year-old Lemohang Tsikoane.

“They tell you plainly that they will not buy from us for M8 when the Chinese are selling for M4.

“The Chinese never used to sell to individuals but now they are doing that. They have come into our market and we cannot compete with them,” says 39-year-old Lebellang Tsikoane.

“They are killing us slowly and the government is not fighting for us as all.

”

‘Mamatebele Kotoane, another farmer who benefited from SADP and has greenhouses close to Teyateyaneng town, shares the same quandary as the Tsikoane sisters.

Kotoane says she is failing to compete with the Chinese. She has three greenhouses, two from SADP and one from the Ministry of Trade. “Basotho Farming has pushed them us of the market,” she says.

“We don’t have the financial capacity to compete as emerging farmers. The Chinese sell their produce at a slashed price because they produce more.

”

Kotoane’s borehole has also dried up and she is using her car to fetch water from a nearby pool that might soon run dry as well.

So whereas the Chinese use gravity to push the water into the greenhouses Kotoane has to load containers and drums into her car. She has hired two employees who she is now struggling to pay.

The Chinese are beating her on both production and marketing. That makes Kotoane angry because she doesn’t believe foreigners should be allowed to invest in small projects.

Kotoane’s plight is shared by a couple other greenhouse owners in villages around Teyateyaneng. But they should not expect the government to intervene because it sees nothing wrong with the situation.

Minister of Agriculture Mahala Molapo says there is no problem with the investors coming into the country. The Chinese project, the minister says, is helping local people because they no longer import vegetables from South Africa.

“We still need more investors to come into the country,” Molapo says. He says project has created employment opportunities for locals.

Molapo says he does not agree with people who complain that the project is a threat to local farmers. “We need to produce locally as you can be aware of the SADP which is aimed at promoting and empowering the locals.

”

He says the Chinese are not a problem because they sell to big supermarkets.

“Basotho should emulate what the Chinese are doing.

”

He says the government should be grateful that there are investors using land that had remained fallow for years.

The minister is thus telling peasant farmers that they should battle it out with a foreign company that has deep pockets and is probably supported by a generous loan from China.

Lebusa Mokhasi, the local chief, says what matters is that the project is creating jobs. Were it not for that project, Chief Mokhasi says, many Basotho will be loitering the streets.

His only reservation is that the project does not employ women. The farmers in Teyateyaneng are not the only locals squirming about the Chinese. Over the years the Chinese have gradually muscled out locals from the grocery market and are now moving into bottle stores.

A Chinese is at the centre of the wool and mohair fiasco between local farmers and the government. Meraka Lesotho, a company in which Chinese are the major shareholders, not enjoys a state-sanctioned monopoly to slaughter cattle and import beef.

Local construction companies are also feeling the heat as Chinese companies snatch almost all lucrative tenders. All this feeds into the simmering anger at the Chinese businesses.

It’s the same story of frustration in other African countries where Chinese have been granted unrestrained permission to make forays into almost every industry.

While African governments call it a boon for their struggling economies local businesses see it as a curse. True, jobs are being created but that is at the expense of the growth and survival of local businesses.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series on the involvement of Chinese in local business. The idea is to understand the impact of Chinese involvement in Lesotho’s private. The ultimate question is whether the allegation from locals that the Chinese are taking over is true.