Africa-Press – Lesotho. Those who have had the opportunity to discuss France’s Africa policy with President Emmanuel Macron are struck by his pugnacity and quick-wittedness. His in-depth interview with The Africa Report / Jeune Afrique has, however, puzzled more than a few observers, particularly those inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Sceptics, on the other hand, are claiming victory. From the outset, they denounced the effort to pass off what in their eyes amounted to a mere publicity stunt as a major overhaul of Franco-African relations.

How, exactly, can we say they are wrong? Indeed, Macron showed a blatant lack of historical imagination, nor did he utter anything of political consequence. He failed to put forward a single idea.

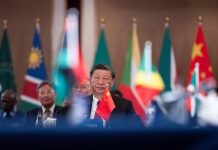

A quick perusal of his interview leaves readers with the strong impression that France aspires to one thing only on the African continent, while simultaneously agreeing to recognise the crucial role Africa has to play in the 21st century, and that thing is to make money. Cynicism and national interest Better still, France aspires to make money à la China and its coldly predatory imperialism.

China, the newcomer that the West readily paints as repellent by day, but, by night, they cannot help but admire the Red Dragon as it happily loots Africa and which, all without troubling itself with God knows what civilising mission, forces Africans to use their natural resources as well as other property as collateral, and to sell everything, in the hope that they will be able to pay off the massive debts they owe, the bulk of which corrupt elites will have embezzled.

Is this description an exaggeration? Hardly. Is it surprising? No more than usual. In many places around the world, liberalism has become mixed up with nationalism and authoritarianism.

Very few states or regimes today can honestly say that their conduct is as irreproachable as their scolding of other countries would have us believe. Why, in the new race for dominance in Africa, would France deprive itself of the advantages its competitors have scarcely relinquished?

Macron wants France to demonstrate the same brand of virility without the nation’s colonial past being thrown in his face at every turn. Macron wants France to demonstrate the same brand of virility without the nation’s colonial past being thrown in his face at every turn.

Or without being reminded time and time again of his hypothetical duties in terms of defending democracy, human rights and civil liberties. After all, if Africans want democracy, why don’t they pay the price themselves?

We have to acknowledge that relations between French leaders and Africa under France’s Fifth Republic have consistently been driven by military and business interests.

In this regard, neither age nor generational gaps play a role, except perhaps an ideological one, like today. Nor do feelings, whether love, hatred or contempt. The national interest, meaning one or two lucrative contracts gleaned here and there, is all that matters. Dramatic loss of influence

If, in this universe of thieves, cold calculation and cynicism prevail, what distinguishes Macron from his predecessors? Has he improved on their ability to accurately assess what is playing out, namely, France’s dramatic loss of influence in Africa since the mid-1990s? It doesn’t matter that some people lament this development while others revel in it.

Either way, we have certainly reached the end of a historical cycle. France no longer has the resources to sustain its African ambitions, assuming that the country still has a clear idea of what they consist of.

Oddly enough, both in Africa and in France, the fantasy of the latter’s power lingers on. Both sides continue to think and act as though France can still afford to do whatever it wants on a continent that itself has been weakened by a half-century of gerontocracy and tyranny.

In his own way, the French president tried to change the direction of things. But he refrained from demystifying the fantasy, even though it needs to be eradicated.

Seeking to enhance France’s attractiveness, Macron’s first order of business was to tackle public perceptions, which brought about the development of several inexpensive initiatives likely to yield tremendous symbolic dividends.

One such project involves repatriating African artworks held by French museums. Another example is Saison Africa 2020, a project which derives more than half of its budget from public funds, but Macron curiously stayed out of sight when it was launched, in a departure with tradition.

Meanwhile, the CFA franc has yet to disappear. Although battered, violent and corrupt regimes continue to be put on life support. The continent witnesses an endless parade of military operations, despite the fact that, thus far and above all else, they have resulted in a never-ending expansion of jihadist groups and related drug cartels and smugglers.

With thousands of troops deployed in various African conflict zones, the military has become, alongside the French Development Agency, the main provider and consumer of stories representing the French across the continent. As for the rest, managing risk, especially when it comes to migrant flows, and remote management will suffice, the thinking goes.

Have we really taken stock of the contradictions that keep piling up? How can we clear up a dispute whose existence we insist on either denying or downplaying its importance? Have we gotten the message that, far from being temporary, the discredit into which France has fallen is a structural and multi-generational issue rather than the result of a few ex-colonies’ penchant for victimisation?

Anti-decolonisation arguments Since none of these challenges have been tackled head on, it should come as little surprise that the gestures Macron takes for clear overtures in a debate that he would like to be open, “uninhibited” and free of taboos, arouse little interest among those to whom he would like to get his message across. The fact that he often fails to pinpoint the right solution to key issues only deepens the level of misunderstanding.

What is gained, for instance, by inserting Franco-Turkish-Russian infighting into the mix of the Franco-African dispute? And what can be said about his remarks regarding colonialism, that other aspect of the dispute? Would there be this level of misunderstanding about the exact nature of the relationship between history and memory, to the point that we mistake one for the other, if the requisite reflection process had been completed beforehand and experts’ findings put to good use? When Macron refers to colonialism in northern Africa as a “crime against humanity” and then goes on to describe it as a “mistake” above all else in sub-Saharan Africa, he is taking one step forward and two steps backwards.

It would be tempting to overlook such trifles if they didn’t reveal the structure of a line of thought about Africa, one whose driving forces can be found in the work, in vogue in secularist and conservative right-wing circles, of anti-decolonisation theorists.

Though France is home to some of the world’s leading experts on Africa, the country would rather base its strategy on an ideological movement that has made fear of Islam its stock-in-trade and the spectre of “communitarianism” its cash cow.

How else are we to interpret the approach that consists of chalking up all of France’s setbacks in Africa to a supposedly deficient pan-African system, while no one bothers to explain to us why said system should be directed more so against this particular former coloniser than any of the rest of the lot?

Moreover, to say that criticising racism paves the way for “separatism” is perhaps a way to score points with conservative right-wing, if not far-right, ideologues and nationalists of all stripes.

But outside of France’s borders, such assertions are not only beyond comprehension – they ride roughshod over the intellectual contribution of Africans and their diasporas to the general conversation surrounding human emancipation and are not at all useful in analysing and understanding contemporary Franco-African issues.

A voice going largely unheard In reality, France and the African tyrants it has backed single-handedly since 1960 are primarily to blame for the nation falling into disrepute in the eyes of the youngest generations.

The neo-colonial cycle initiated by General Charles de Gaulle during the Brazzaville Conference in 1944 has fizzled out. Put into action immediately after the official start of the decolonisation process, the cycle has reached the end of the road.

It lost its main driving forces at the end of the Cold War when France abandoned its “African provinces”, with their hands tied, to the tyranny of the Bretton Woods institutions and began its own neoliberal shift.

Without necessarily burning its boats, the former colonial power has continued to divest itself of its main assets on the continent, setting off in the process a series of decouplings that it can no longer contain.

Higher tuition costs for foreign students in France, nearly 45% of whom are African, is a glaring illustration of one such consequence. China currently has around 80,000 African students.

For now, there is no indication that the bloodletting has stopped at any point over the last four years. On the contrary, the picture is more mixed than ever before.

If a political voice is there, it is going largely unheard. The act of producing analysis and forecasts has fallen into the hands of military task forces. The Presidential Council for Africa conducts itself more like a non-governmental organisation than as a source of forward-looking ideas.

Choosing members of the African diaspora to represent the civil arm of a pro-business crusade doesn’t seem to be grounded in any proven sociological reality.

On the contrary, it runs the risk of reviving the race to accumulate private wealth and tendencies towards corruption, at a time when the focus should be on strengthening communities’ cultural and social capabilities as well as protecting civil liberties. Transforming France’s vision of Africa

It may turn out to be that, for the current and future generations, France will ultimately have nothing more to offer than a good old-fashioned pact, under which Africans agree to forget the colonial past and work diligently to cultivate a new ethos based on a love of business and a passion for profit, swiftly disguised as “entrepreneurship” and militarism.

But that isn’t the only potential pathway. Macron himself is persuaded that a mere change in style won’t be enough to bring about a paradigm shift. Rebuilding actual historical and forward-looking analysis capabilities is what needs to happen.

Above all, at a time when the isolationist temptation is real for the French people, transforming France’s vision of Africa from the ground up is a must. Such a long-term political and cultural undertaking can only be accomplished independently of electoral calendar constraints.

Out of every country in Europe, France has the richest social, diplomatic, intellectual, artistic, economic and scientific capital when it comes to Africa. It also has a great deal of good intentions.

The fact that we have reached a point where the Chinese delusion, a mixture of greed, authoritarianism and militarism, is the only alternative available to Africa’s rising generations demonstrates the force with which this multifaceted capital is being squandered and the historical imagination emasculated.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press