Africa-Press – Lesotho. Africa is emerging as an attractive trading partner for Germany amid a global realignment forced by Russia’s war with Ukraine and growing concerns with supply chain reliance on China.

Christoph Kannengiesser, CEO of the Berlin-based German-African Business Association (Afrika-Verein), tells The Africa Report that German businesses have long overlooked the continent in favour of lucrative markets elsewhere.

But rising tensions with Moscow and Beijing have forced a rethink and put the region in a new, positive light. “Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine represents a clear break in German foreign and economic policy,”

“African countries, which have so far received only marginal attention, are now emerging as attractive partners.

” Now 90 years old, Afrika-Verein counts 550 members who account for 85% of German business interests in Africa.

Its members work in numerous sectors from financial services, energy and manufacturing to chemicals, pharmaceuticals and shipping and include such giants as Allianz, Airbus Defence and Space, BASF South Africa and Bayer.

Economic indicators point to the continent as the next major growth region in the world, adds Martina Biene, managing director and chairperson for the Volkswagen Group South Africa (VWSA).

Biene is the first woman to lead VWSA since the world’s largest automaker began operating in South Africa in 1946. She says the company is determined not to miss out on the wave of growth coming to Africa, home to the world’s fastest-growing middle class.

In all, some 600 German companies are doing business in South Africa, with total trade between the two countries adding up to R266bn ($14.7bn) a year.

South Africa exports value-added goods to Germany worth R155bn ($8.6bn) annually, according to official figures. In 2021, German direct investment into Africa amounted to €1.6bn ($1.7bn), with €1.1bn ($1.2bn) going into sub-Saharan Africa.

That represents less than 1% of Germany’s foreign direct investment – a figure the government wants to change. One immediate consequence of the conflict in Ukraine has been Germany’s overnight scramble to secure new energy suppliers.

For more than a decade, businesses and households in Germany and the rest of Europe had enjoyed a steady stream of Russian gas flowing through the 1,200-km Nord Stream pipelines running under the Baltic Sea.

With the capacity to transmit as much as 55 billion cubic metres of gas a year, the twin pipelines were projected to secure Europe’s energy supply for the next 50 years. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has upended that assumption.

According to the Afrika-Verein, the continent is well positioned as an alternative source for Germany’s energy needs while helping efforts to diversify supply and value chains. Senegal’s gas fields could ease the German energy bottleneck while Namibia offers the potential to produce green hydrogen, says Kannengiesser.

The African Energy Chamber, a South Africa-based trade group that bills itself as “the voice of the African energy sector,” aims to capitalise on the positive sentiments to unlock European investment into a continent that requires up to $1.7tn to boost upstream gas production in order to become a significant force in global gas supply.

The African Energy Chamber — in partnership with the African Import-Export Bank and market research firm Rystad Energy — is on an energy investment charm offensive in Europe that kicked off in London and Oslo in January.

On 23 February, the chamber hosted an Invest in African Energy Reception in Frankfurt to argue that the continent holds the keys to Europe’s energy crisis.

“German companies have the technology and expertise that Africa needs,” says NJ Ayuk, the chamber’s executive chairman.

“We hope Invest in African Energy will foster a new era of improved cooperation.

” The recognition of Africa’s potential as a partner and market for German goods and services extends beyond commercial considerations.

The corridors of political power are also awakening to the continent’s strategic importance, with several ministries in Chancellor Olaf Scholtz’s administration updating their Africa strategies to align with the shifting international dynamics.

German companies have the technology and expertise which Africa needs. In May 2022, Chancellor Scholtz embarked on a visit to Senegal, Niger and South Africa accompanied by a German business delegation keen to deepen trade, investment and energy cooperation.

Scholtz’s second-in-command, Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck (who is also the German Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action) followed suit in December with visits to Namibia and South Africa.

“The fact that ministers are increasingly visiting countries like South Africa, Namibia, Senegal, Niger, Ethiopia, Nigeria or Mali [means that] African countries are gaining in importance for the German administration,” Kannengiesser says.

“German politicians are also becoming increasingly aware that the German private sector is an important partner in cooperation with African countries,” he adds.

Kannengiesser points to reforms to the instruments of foreign trade promotion by Habeck’s ministry as evidence of new German thinking about Africa. The German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development’s new Africa Strategy is another example.

Germany is also leading the charge in engaging with Africa at the multilateral level, says Kannengiesser. The G20 Compact with Africa was initiated under the German presidency in 2017 to promote private investment on the continent, he points out.

Along with the 2021 European Global Gateway Initiative that provides the framework for the European Union’s external investment, these efforts signal a new normal with the continent.

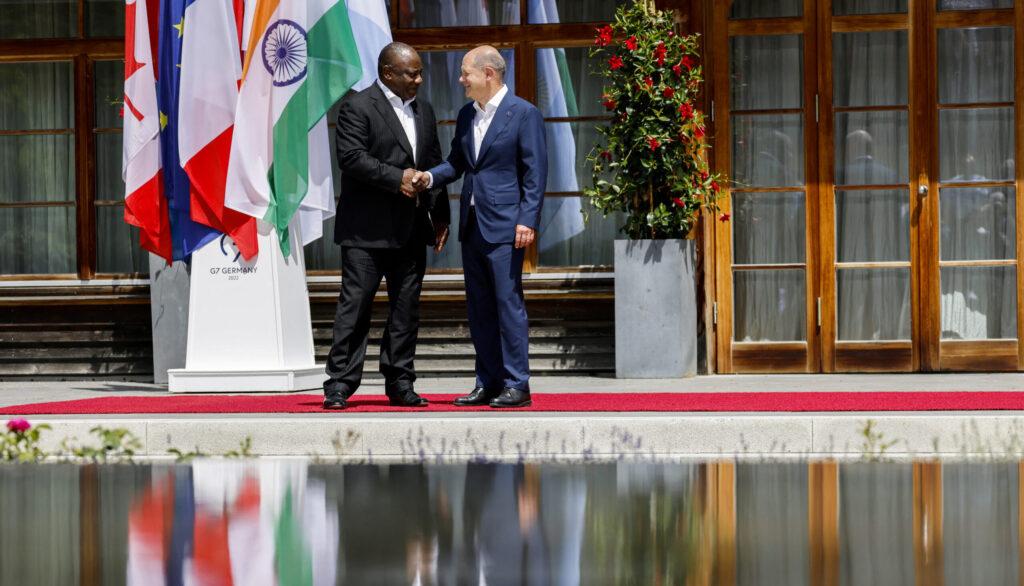

And just last June, Scholtz invited President Cyril Ramaphosa to attend the G7 Summit in Munich as his guest. The German chancellor said at the time of his visit that he considered South Africa a key partner country.

Despite all the rhetorical overtures, Kannengiesser says the German government needs to do more to meet the demands for more private-sector cooperation that Afrika-Verein hears from its African partners.

“Unfortunately, we still see far too few concrete approaches to effectively support German companies in Africa by the German administration,” he says.

In addition to interest in the energy sector, Kannengiesser notes that East Africa is experiencing a boom in the circular economy, which emphasizes reusing products, while South Africa is becoming an attractive market for German electric cars.

VWSA operates the biggest car factory on the continent in Kariega, in the coastal province of the Eastern Cape. There the company builds several models from its Polo line of cars, employing about 4,000 people.

Biene says VW believes in the region’s potential. “Everywhere I go, I tell everybody that we want to venture into Africa — and that we’ve started that journey already,” she says.

The VWSA boss has a laundry list of items that the German government and African states can assist with to boost the auto industry on the continent. “We need support in vehicle production,” says Biene.

“We would want Germany to encourage suppliers to come to Africa together with us as an OEM [original equipment manufacturer] to be in a position to manufacture or do more than vehicle assembly.

“Supplier investment, or supplier encouragement, is one area where Europe can support us. Also, bringing the right skills, especially on the supplier side,” she adds.

“How can you grow an industry to the level and standards that we as a European heritage manufacturer would be happy with? Skills transfer, education [and] encouraging suppliers.

Biene adds that Africa can help lay the groundwork for future investment by tightening up its regional auto policy, looking into the development of cleaner fuels and curtailing a sizeable second-hand car market.

VWSA’s approach to the region is aligned with that of the African Association of Automotive Manufacturers. “We need automotive policies to increase new car demand and to come to a threshold of vehicles.

The same applies to South Africa,” says Biene. “What limits investment on local content is that we need more volume. ” The Kariega plant has the capacity to produce an estimated 165,000 units a year.

“For many suppliers, that is not the best threshold,” Biene says.

“We would need more volume.

” The Kariega facility is on the smaller side for VW and is comparable to the Osnabrueck and Pune plants in Germany and India.

“The higher the production numbers, the better the localisation, and the more attractive for suppliers,” says Biene.

Biene says she asked German Automotive Association President Hildegard Mueller to support the drive for cleaner fuel quality during Mueller’s recent visit to the region.

Poor fuel quality “limits us, to a certain extent, in terms of models we can supply,” Biene says. “We don’t have the engines to supply [for] such bad fuel quality.

” Cleaner fuel would also help address environmental challenges, including climate change.

“Better fuel quality would enable better technology in the engines to reduce CO2 emissions and the CO2 footprint of African countries,” Biene adds.

Despite the challenges, she says Africa’s economic potential is “huge” — and German companies such as VW want in. “I think Europe has realised this is the one and only growing region where it would be good to be part of when it kicks off,” she says.

“Everybody wants to tap into it. And we want to be in the first wave.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press