Africa-Press – Lesotho. South African writer, Nhlanhla Maake’s novel, Letters to My Sister, is what is called an epistolary novel. This is a novel told through the medium of letters written by one or more of the characters.

This term comes from the word ‘epistle’ which means letter. Some speak more broadly and say an epistolary work of literature is one written through a series of documents.

Most often, these documents are letters, though they can also be diary entries, newspaper clippings, and, more recently, blog posts and emails. Pamela by Samuel Richardson (1740) is considered one of the earliest epistolary novels in English.

In African literature, Mariama Ba’s So Long a letter is a famous example of an epistolary novel. It is written in the voice of Ramatoulaye who is a school teacher in Senegal.

It is addressed to her friend called Aissatou. The letters relate Ramatoulaye’s emotional experiences after her husband’s second marriage and his death.

The advantages of the novel in letter form are that it presents an intimate view of the character’s thoughts and feelings without interference from the writer and that it conveys the shape of events to come with dramatic immediacy.

Also, the presentation of events from several points of view lends the story dimension and credibility. In other words, epistolary novels do not need omniscient narrators to explain what every character is thinking and living through, because we as readers get access through their own words.

Epistolary novels can be further classified into three very broad groups. First, there is the monologic epistolary novel which is made up of letters or diary entries from only one person throughout, with no responses from the recipient as in The Colour Purple and Letters to My Sister.

The second type of the epistolary novel is the Dialogic epistolary which is a novel with letters between two characters as in David Mutasa’s Nyambo Dzejoni.

The third type of epistolary novel is called the Polylogic which is a novel with three or more characters who write letters to one another in no particular order. It is known that other epistolary novels may combine all or some of the above techniques.

Some of the novels like Charles Mungoshi’s Branching Streams Flow in the Dark are partial epistolary novels as the letters form may not be sustained throughout the novel.

Letters to My Sister was first published by Heinemann in the Sesotho language as Mangolo a Nnake. It was later translated to English by the author and became republished 2012.

In this novel, Ntšebo, who lives with her husband in the area around Thokoza and Katlehong in Johannesburg, South Africa. The woman writes letters capturing the turmoil in these areas towards the 1994 watershed election. She is writing these very personal letters to her sister, ’Masechaba who is in their home country, Lesotho.

In 1990 the National Party government entered into negotiations with opposition groups and liberation movements leading to South Africa’s non racial elections in April 1994, however that four year period sparked maybe the bloodiest political violence in South Africa.

This is the period that this novel covers. Through these letters the reader notices that there is very chilling violence between black people of different politics and tribes and between people of the hostels against those who stay in the proper residential location.

They appear to be instigated by the apartheid system to kill each other. The system is also arming one group against the other. In the most horrendous letter of 1 June 1991 Ntšebo indicates that a woman of the proper township is dragged from a taxi by a hostel mob who keep her for weeks in the hostels as they gang rape her.

They sometimes take her to the city to buy her groceries and return to the hostels to eat and gang rape her again. One day she escapes through the back door of a city shop where they have taken her to buy the groceries. Sometimes they enact unlawful roadblocks and take dozens of people from the taxis to go and slaughter them en masse.

At a funeral, when the burial rituals were completed, before the coffin descends into the grave, the hostel mourners draw their spears and rush into township to avenge the death of their friend and after sometime they return to the cemetery with their weapons dripping human blood.

After the funeral, they return to the hostels to wash hands in the bath tub and a man sees that the tub does not contain only water but also blood and human parts cut into pieces.

He also sees a human ear floating in the water. In these letters to ’Masechaba, Ntšebo does not write about the violence visited on the residents by people from the adjacent hostels only.

She also chronicles how her relationship with her husband, Abuti Molemi, is faltering. Eventually they separate. The unequal relations between men and women in African society, comes to the fore through this novel.

Ntšebo’s Sesotho world view also comes out clearly in all these letters as she throws in Sesotho proverbs and sayings. Since time immemorial, the epistolary novel allows a novelist to create a character who is at a moment of pouring out with no inhibitions.

It is assumed that the character is writing in the personal and intimate situation that only a letter provides. As you read, the letter form allows you to snoop into the supposedly unedited materials.

Confidential space also becomes public. Ntšebo writes letters to ’Masechaba for two years. She starts from 2 January 1991 to 11 August 1993, sometimes once a week, then once a month and eventually once in two months.

In this book, you sense Ntsebo’s heart beat even when she sometimes receives no responses from her sister in Lesotho. Her first letter begins with: “’Masechaba, My dear sister.

I am writing this letter in bed, without anyone looking after me…I don’t want to bother you with my problems, because I know that you have your own difficulties…”

The above takes you to how the epistolary has capacity to employ verbal irony.

If Ntšebo does not want to bother ’Masechaba, then exactly why does she write all these letters? What could be her intention of writing, if it is not to share her problems? She is the skillful and folkloric African narrator with capacity for double talk too.

You even ask yourself, why doesn’t Ntšebo phone and chat? Why write all these letters? But you recall that this is South Africa of 1991 and there is no easy phone technology like we have now in 2021.

But, as if anticipating this question, the author causes Ntšebo to write: “I would call you if I could, but the phone line was disconnected in the year just gone by, during the month of August. He has been promising that he would settle the bill so that they should reconnect it, but up to this day he has done nothing about it.

”

From the very start, this epistolary novel continues to be aware of the existence of the phone as a competitor to the letter form and insists on finding technical reasons why Ntšebo is using the letter and not the phone.

In her third letter, Ntšebo says that the phone is not yet fixed and that is why she is not phoning and resorting to writing letters. In the fifth letter, she admits that at least she had phoned and spoken to ’Masechaba but she failed to phone again hence writing the fifth letter.

When Ntšebo writes the seventh letter, she says it is necessitated by the fact that she does not know if her previous letter reached ’Masechaba and that many things have taken place in the interim, forcing her to write again.

Two letters down the lane, Ntšebo gives another very technical reason for writing instead of phoning: “I wonder whether you received the last two letters that I wrote you last month? I am so broke that I can’t even go to the post office to phone you.

I have to save every cent that I have for food. ”

The epistolary also continues to defend itself by explaining why Ntšebo continues to write instead of visiting family in Lesotho.

Sometimes she explains why she has taken too long without writing another letter or why she has written again just within two days of the previous letter.

All these are some of the key demands of the epistolary novel because all the gaps and silences or omissions have to be explained to the reader. The relationship between Ntšebo and her husband runs parallel to their unpredictable relationship with the low life people of the hostels.

When the killings perpetrated by hostel people start, Ntšebo’s husband and colleagues like abuti Lefosa, form special community based patrol groups to protect their residential area. Molemi and Lefosa appear like decent and well to do men who are lawful and responsible.

But as time goes on, Ntšebo notices that the respectable Lefosa is being supported by Ntšebo’s husband to conduct an illicit love affair with a lady whom he calls “my uncle’s daughter.

” Soon Lefosa disappears with no explanation. Ntšebo soon notices that her own Molemi is also having lots of love affairs instead of being just on patrol. At that level, we might say that this epistolary novel operates also as a detective novel.

First; Ntšebo notices that Molemi comes home with his underwear worn inside out! She writes: “As soon as he came in, I put his food in the oven…He said no thanks, he was still ok…when he came to the bedroom and prepared to go to bed, I was surprised to see his underpants inside out and one of his socks was also inside out…I remembered that when he left in the morning I was awake and saw that he was properly dressed.

”

All this hints to the fact that Molemi must have had taken off his pants and stockings somewhere away from the home! Ntšebo also starts to notice that her husband is now falling asleep as soon as his head hits the pillow.

He no longer has his usual sex drive. She also observes that the car windscreen sun flaps are always down on the passenger seat side. This means that there is now some woman sitting on that place in the car at sunset every day with Molemi.

Ntšebo also notices that when her husband gets home in the night, he leaves the car several blocks away and walks into the yard to have sex with the woman in their outer house.

After the game, she notices that he then goes back stealthily to the road and drives the car into the yard, pretending to just having arrived!

Eventually Molemi is over-excited about the sex he receives from the woman in the outer house that he buys a bed for the woman.

But those who deliver the bed thinks it is for Ntsabe and take the bed to Ntsabe in the main house yet the name indicated in their papers is of the woman in the outer house.

Finally Ntsabe cannot stand it and she moves out of the house to find a shack in a different location. By the time the story ends, they are staying apart.

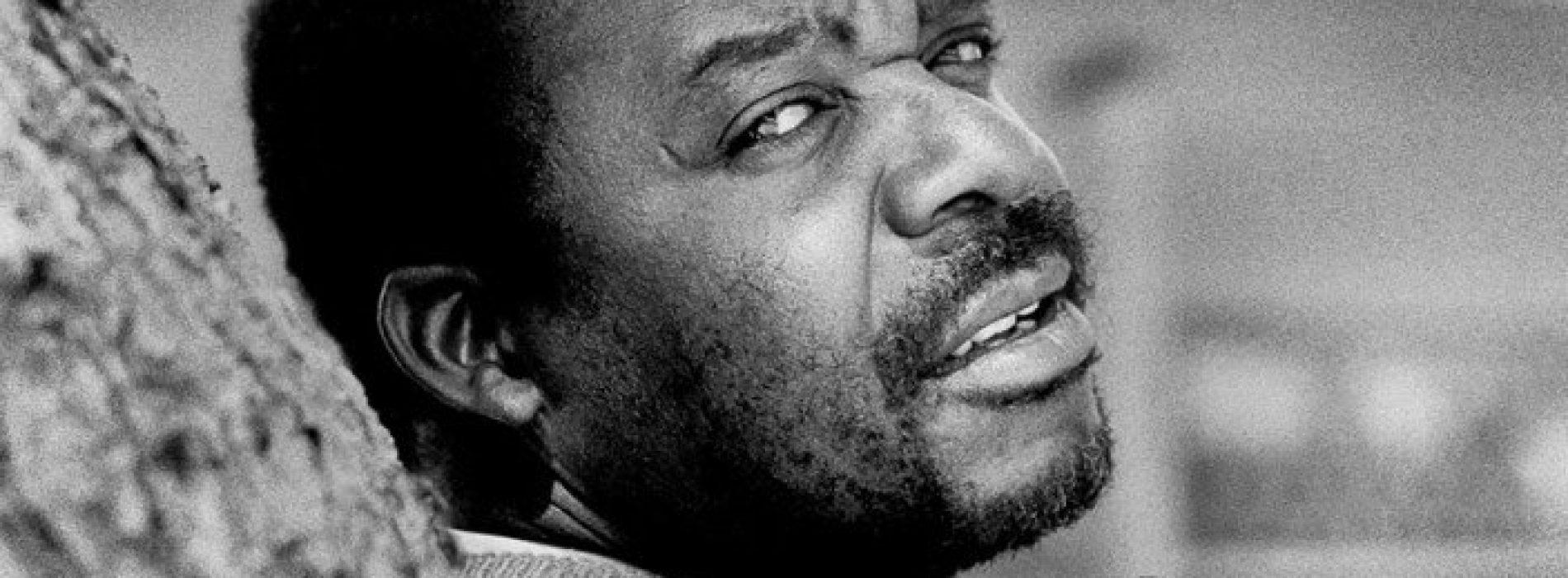

But Ntšebo goes to school to learn to design and make clothes. Finally she is able to look after herself. She has found her freedom at last. The author of this novel, Nhlanhla Maake, was born in Eastwood (1956).

He grew up in Thokoza, attended primary school there and in Eastwood and matriculated at Immaculata High School in Soweto. He took degrees at the University of the North, University of the Wits and others.

His novels won the Erns van Heerden Creative Writing Award, MNET Book Prize and the African Heritage Literary Award. Maake has published more than twenty books of fiction and non-fiction in Sesotho and English. He is married and is a grandfather.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press

![THE RULING PARTY [RFP] LAUNCHED FIRST DIASPORA COMMITTEE THE RULING PARTY [RFP] LAUNCHED FIRST DIASPORA COMMITTEE](https://static.africa-press.net/lesotho/sites/62/2026/02/sm_1771878934.036281-218x150.jpg)