Africa-Press – Lesotho. Ramaphosa’s early years as a young militant shaped him into the leader he is today. For 90 minutes on 7 February, Cyril Ramaphosa held parliament in his hand as he set out the ambitions for his presidency.

In a sombre grey suit and tie, fitting his soubriquet as ‘South Africa’s CEO’, Ramaphosa reeled out his agenda for the coming elections: inclusive growth, jobs, better schools and training, stepping up the fight against corruption and strengthening the state to meet the people’s needs.

“It was 100% Cyril,” said a veteran African National Congress (ANC) cadre in Cape Town’s parliament square afterwards.

“Thoughtful, well-crafted, something for everyone.

” Then he paused: “But can he deliver on any of this? His house is divided. The looters are not in jail. Growth is worse than stagnant and we’re losing more jobs.

” So why the euphoria after Ramaphosa finished speaking? “Because we all want to believe in him. He’s won the ANC over 55% of the vote already. Job done. ” Ramaphosa has set the ANC on course for a victory that would suit him.

It has to be over 55% of the vote to reverse the party’s decline during Jacob Zuma’s era, but not a landslide – which could encourage complacency. To lead the ANC now – 25 years after its victory in South Africa’s first free elections – requires an extraordinary set of skills.

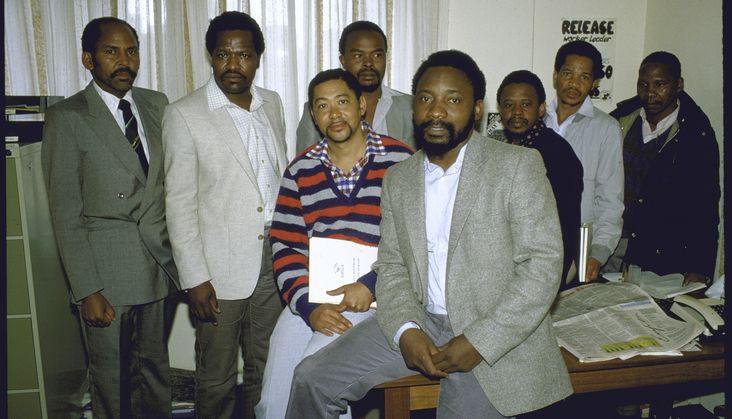

That Ramaphosa – the student activist, the militant unionist, the political organiser, constitutional negotiator and then corporate titan – has those skills is evident.

Less obvious are his people skills. Many who have worked closely with Ramaphosa say they do not know the man. Proudly announcing “I’m an enigma,” Ramaphosa revels in this psychological inaccessibility, rare among such ubiquitous public figures.

Outgoing and gregarious, Ramaphosa works a room with a natural gift for recalling faces and personal stories. Rising at 5am, he has taken to power walking, with security in tow, chatting animatedly to the early-morning workers he meets en route.

In the popular mind, that somehow offsets his country-gentleman-style enthusiasm for fly fishing, golf and expensive herds of Nguni and Ankole cattle.

Allies say it points to Ramaphosa’s chameleon-like qualities, which have steered his career: from pushing Harry Oppenheimer to raise miners’ wages to becoming a mine owner himself. Destiny is a recurrent theme in Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa’s life.

From his confident teenage prediction to journalist Denis Beckett that he would one day be president of a free South Africa to his current position in just that job, Ramaphosa’s path has been accompanied by a strong belief that he is on the right side of history.

Even when recalling his setbacks in politics and business, Ramaphosa reflects that they often worked out for the best. Born in Johannesburg on 17 November 1952, Ramaphosa arrived at the end of an auspicious year.

There was a general strike against the latest depredations of the apartheid regime. The ANC had launched its ‘Defiance Campaign’, protesting against the repressive and discriminatory laws that banned interracial marriages and compelled black South Africans to carry passes in towns and cities.

ANC militants responded by burning the hated passes at public rallies. In Soweto, where Ramaphosa grew up on Mhlaba Drive, the militancy grew. Aside from his studies and his Christian beliefs the young Ramaphosa liked to sing and dance but politics soon became an all-consuming passion.

I think this time [his 1974 detention] had a profound impact on Ramaphosa” – Letepe Maisela His parents, Samuel, a police officer, and Erdmuth, tried to protect their son from the regime’s brutalities.

He later recalled how a white soldier kicked him into a ditch at the age of seven. The following year, police shot dead 69 protesters, wounding hundreds more, at Sharpeville, not far from the Ramaphosa family home. Then the regime banned the ANC and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). Suddenly, the anti-apartheid struggle became an international cause célèbre.

After finishing high school in Sibasa, in present day Limpopo Province, Ramaphosa left home to enrol at the University of the North, known as Turfloop, just as African students stepped up their campaign against discrimination.

Ramaphosa, who was studying law, threw himself into student politics. “He was the quiet type, not one to boast but someone students liked and looked up to,” businessman and author Letepe Maisela, who was at Turfloop with Ramaphosa, tells The Africa Report.

After the regime cracked down on student politics, Ramaphosa used the Christian student movement to organise protests against apartheid, says Maisela.

“He was a natural leader and students listened to him.

” In 1974, Ramaphosa was detained for 11 months under the Terrorism Act.

“I think this time had a profound impact on Ramaphosa, [although] he doesn’t talk much of the solitary confinement,” says Maisela.

Ramaphosa spoke in parliament this year about his detention, responding to accusations from Mosiuoa ‘Terror’ Lekota, an activist at the time, that he had sold out his comrades to the apartheid security police.

“My arrest was quite dramatic and I was taken to Pretoria Central police station.

They started to interrogate me, which was quite vicious. I will not go into that.

” He said the police tried to force him to give evidence against his comrades, including Lekota.

“And I refused. And they thought they would use my dad to put pressure on me to agree to become a state witness. I refused. I said I will not do it.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press