Africa-Press – Lesotho. Many of life’s failures are people who did not realise how close they were when they gave up. That famous quotation is attributed to Thomas Edison, the man who invented the electric lightbulb that has proven to be arguably one the greatest inventions mankind has ever made.

Miloane Mokhobo was in that bracket of men who were close to quitting when the going got tough. That was not because he had not tried. He had experimented with several business ideas which had all spectacularly failed.

His worst moment came in 2016 when he took a flight to Nairobi, Kenya, to pitch a business idea, blowing M22 000 on the trip only to be informed on his arrival there that the meeting had been cancelled.

A year later, Mokhobo began a cosmetics manufacturing business. He packaged petroleum jelly (Vaseline) and olive oil for cosmetic use. “We invested M24 000 in that business and it too failed,” he says.

“It was one of the most painful moments for me.

” He then hit the streets selling T-shirts and sweaters which were printed ‘Lesotho Mzuku’ and ‘Haeso Mzuku’.

He says there was a time when he felt like he had already invested too much energy and resources in business but all without tangible results. “I felt like without it there was no bright future for me, it was a matter of do or die,” he says.

It was these failures that were to soon act as a launch-pad for a thriving multi-million agribusiness. In 2019, Mokhobo set up Wild Plants Growers (Pty) Ltd which is based in Mohale’s Hoek specialising in the production of wild plants which have commercial value.

The main products of Wild Plants Growers are whole berry rosehip, Rosehip shells, rosehip seeds and pelargonium sidoides (African geranium). “We are currently generating revenue of M3 million,” he says. Mokhobo was born and raised in Mohale’s Hoek.

After completing his Cambridge Overseas School Certificate (COSE) in 2007 at Likuena High School, he enrolled at the National University of Lesotho (NUL) where he studied for a Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology. In 2013, he got an internship at the Ministry of Trade.

He says he was doing research on how to establish commercial plantations of Agave Americana (lekhala le leputsoa) including the design of the farms and the factory for processing cosmetics using agave sap and the costs.

“So it was during this time of my internship that I started reading widely about wild plants that have commercial value,” he says.

He says as the internship was about to end, he started thinking about work opportunities and how he could secure a job for himself. “That’s when the idea of rosehip came to my mind,” he says. Mokhobo proposed to develop the commercial plantations to one of the local rosehip processing companies. “My proposal was given a chance,” he says.

In 2015, he then left to study for a Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology at Pan African University Institute for Basic Sciences, Technology and Innovation (PAUSTI) in Kenya.

He says in his final year, he continued with the research on rosehip. “I was developing a protocol for tissue culture production of rosehip seedlings,” he says.

“When my previous employer heard about the research, he was so excited that he even promised that he was going to build a tissue culture laboratory where I would be working upon completion of my studies,” he says.

However, he says he could not finish up his research due to limited time. “I was about to take only one year of research,” he says. He says he had to drop this research when it was not yet completed.

After he returned home, he says he came with consumables used in the tissue culture lab with the aim to ask for an opportunity to finish this work at the tissue culture lab at any college of Lesotho.

“I tried both but failed,” he says. Mokhobo says he was left with one option — seeking a job. He failed. In 2018, he wrote a proposal to his previous employer asking for a supply contract to supply them with rosehip seedlings again and they agreed.

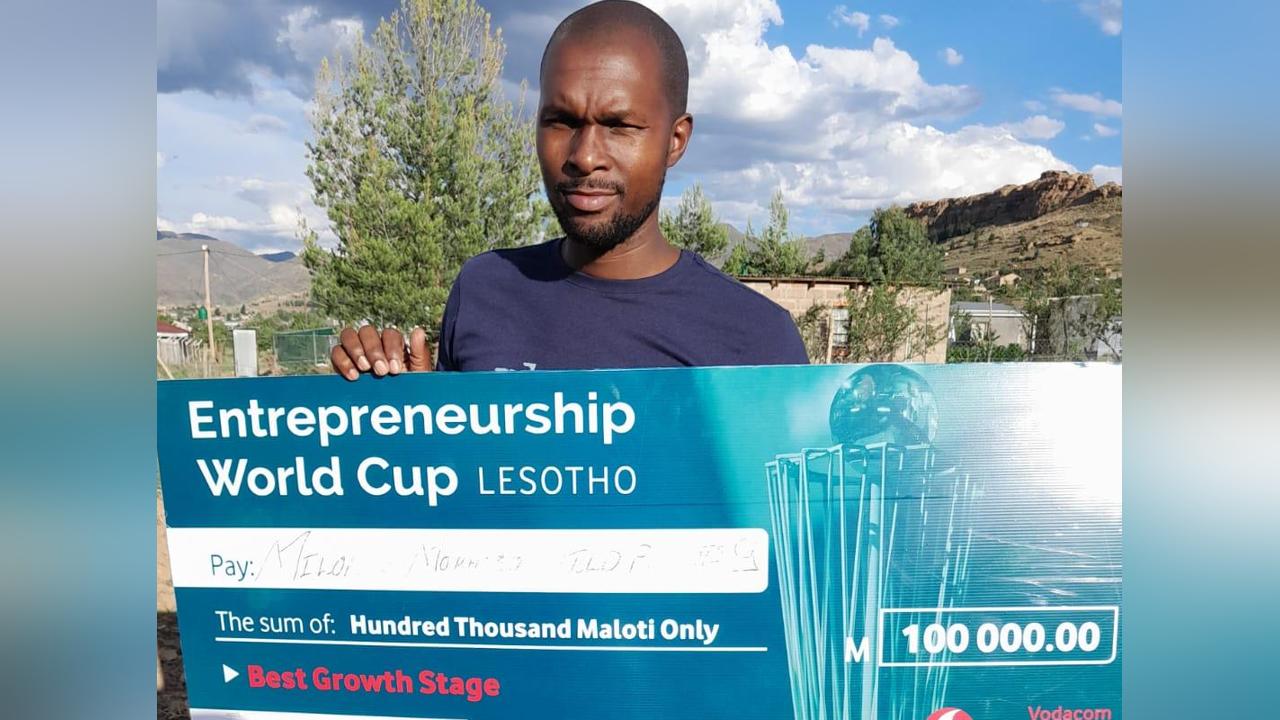

Mokhobo says while he was still struggling to sustain his dream, he applied for the Bacha Entrepreneurship Project (BEP). “I won a whopping M195 000 and that led to the formal registration of Wild Plants Growers in January 2019,” he says.

Mokhobo says the establishment of Wild Plants Grower came after multiple failed projects. He tried beekeeping in 2014 and seed oil extraction from peach and apricot seeds that is usually used in cosmetics in 2016.

Furthermore, he says he applied for the BEP with the idea of processing Aloe forex. He says he then received training on how to write a business plan and basic business management skills.

“When Wild Plants Growers was born I had already learned a lot from the previous failures,” he says. Mokhobo says when the business was developed they did not have enough resources. He needed a greenhouse due to our climate.

“I had to collect small timbers from the nearest forest and plastics from the nearest hardware to make my own greenhouse structures,” he says.

He says because the structure was weak, when it was windy the greenhouse would collapse. Mokhobo says they started with only one client. They are currently supplying South Africa and European markets, specifically Germany.

He says their rosehip is organic certified according to European Union (EU) standards which have opened the market in Europe. “I thank the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Trade hub that paid 50 percent of our initial audit costs,” he says.

Mokhobo says they have established five hectares of commercial plantations of rosehip with additional 20 hectares to be developed before the end of this year.

“We are developing a partnership with field owners who will be enjoying 30 percent sales of the yield from their fields,” he says. Wild Plants Growers plays a colossal role at community level.

This year they have trained 527 wild plant harvesters who are harvesting and selling their rosehip and pelargonium sidoides to them. Wild Plants Growers has now created both direct and indirect jobs for Basotho.

He says they buy rosehip and pelargonium sidoides out of the country thereby providing alternative income to most families in rural communities of Lesotho.

He says currently they are working with 17 farmers on the rosehip cultivation project. They have seven full-time employees. At pick season, he says they hire about 20 temporary laborers working with them at various levels of the supply chain.

Despite the achievement, Mokhobo says the challenges in this industry are overwhelming including the reluctance by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism to issue permits which would allow them to export in time when they are needed.

“I have lost M500 000 worth of pelargonium orders from January up until now,” he says.

“We urge the government to play its role of creating an enabling environment for entrepreneurs to compete and flourish,” he says.

He further explains that since pelargonium is endemic in Lesotho and South Africa, when things like this happens they lose their customers to their SA competitors.

“That’s how overseas companies lose trust in Lesotho companies and so we lose more in the process,” he says.

Mokhobo says the absence of machinery leads them to selling their products as raw products which do not allow them to add value. “This in turn affects our economy because we are not getting much from our sales,” he says.

Through his experience, Mokhobo says he has witnessed big commercial plantations of products such as tea, sugar cane, pineapple and rooibos. “I witnessed the commercial plantation of wild plants growing in the mountains of Western Cape,” he says.

“However I have never seen sizable commercial plantations of certain crops which can generate over 1 000 jobs at the peak season,” he says.

“My dream is to make my own Lesotho Ceres,” he says.

He says he wants to create a place where people can go from corners of Lesotho to get seasonal jobs in winter to harvest rosehip and hopefully other crops that will come at a later stage.

“My dream is to develop 100 hectares of rosehip farm,” he says.

“We spent about M115 000 to establish five hectares of rosehip farm from developing seedlings, transplanting seedlings to the field, and labour related costs including annual field fees for the first year,” he says.

He says the challenge they have is having an additional budget to manage the operations of the established farms such as removing weeds. Mokhobo says the upcoming incubation and trip to Singapore will give their business some global exposure.

“I will be seen not only by potential investors globally but also potential business partners,” he says.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press