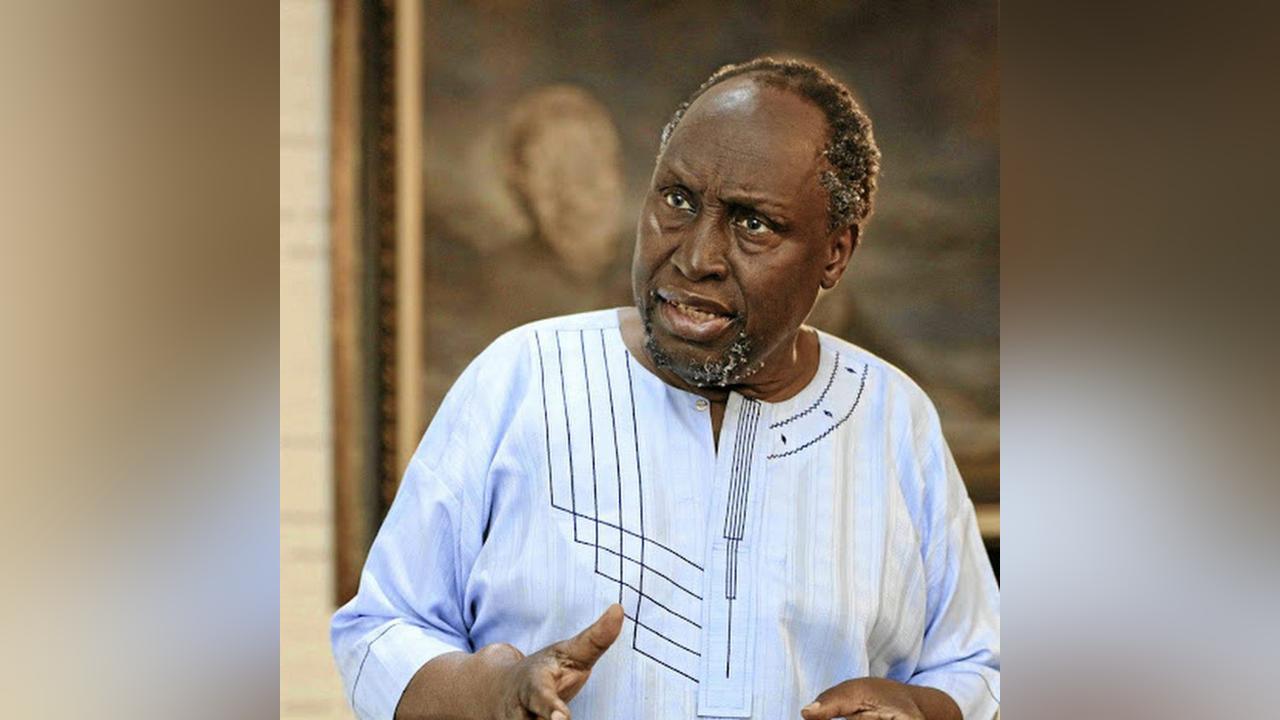

Africa-Press – Lesotho. Ngugi wa Thiongo’s very own life itself, just like his works, continues to intrigue the silent observer. During the first week of June 2023, it was reported by Carey Baraka of The Guardian Newspaper that Africa and Kenya’s foremost literature giant, Ngũgĩ, is going through “a bitter divorce” from his second wife, Njeeri, at a time when he is also ailing in the US.

Kenyan writer and journalist, Carey Baraka, had travelled to California in October 2022 to spend some time with Ngugi. “The plan had been to write a profile, taking the measure of this legendary author, who is now 84 and entering the final phase of his life.

” On the 5th of January 2023, Ngugi turned 85 with the additional great news that he was still writing. Since 2002, Ngugi has been a professor of comparative literature at the University of California, Irvine. Carey Baraka himself is a writer from Kisumu, Kenya who writes about literary culture, food, sports, and politics, among other things.

In this recent report in question, Baraka ascribes Achebe, Soyinka and Ngugi three distinct positions in the literary scene of Africa in the 1950’s and 60’s: “If Achebe was the prime mover who captured the deep feeling of displacement that colonisation had wreaked, and Soyinka the witty, guileful intellectual who tried to make sense of the collision between African tradition and western ideas of freedom, then Ngũgĩ was the unabashed militant.

His writing was direct and cutting, his books a weapon – first against the colonial state, and later against the failures and corruption of Kenya’s post-independence ruling elite.

” On getting to California Baraka finds Ngugi in a morning dress and their relationship, from the report, appears natural and friendly. As you read, it turns out that Ngugi stays alone with the aid of a health aide.

Ngugi has suffered many maladies in recent years and he has gone through various major medical operations and he has had to constantly visit medical centres for routine check-ups.

Baraka makes what I think up to now is the most elaborate ever description of the great writer’s physical appearance and mannerisms: “Ngũgĩ has a slow, slightly croaky voice.

He talks in a Gĩkũyũ accent mixed with traces of the English one he picked up while living in England, often stressing the last word in a sentence.

He peppers his sentences with ‘oh my God’, which he uses to register incredulity at opinions he takes to be absurd. He has a way of being dismissive without being rude, taking a strong stance without quite silencing you.

He is quick to laugh, and when he laughs at something he finds ridiculous, he buries his face in his hands, while shaking his head and saying, “Oh my God.

” When he laughs at something he finds funny, he lifts his hand to the top of his head – bald except for grey tufts of hair above his ears – but then winces, for that movement can be painful for him.

Sometimes, the laugh can descend into a hacking cough, which exacerbates the pain of the incisions he has in his belly from multiple surgeries. . . ” And finally the gauntlet falls: “Ngũgĩ seemed to sense that an explanation of some kind was needed because he said, unprompted, “I know I look like a bachelor, but I’m not.

” He and his wife were going through a divorce. Before the two of them separated, they lived in University Hills, a part of Irvine where a lot of university faculty stay, near the beach. ”

And that above is the saddest part of Baraka’s write up because it draws a picture of Ngugi as a lonely and ailing old man. Apparently Ngugi married in 1961.

Over the next 17 years his first wife, Nyambura, gave birth to six children. His second wife, Njeeri wa Ngugi, he met in 1987 and they have two children. On my own part, Ngugi has always been an immense inspiration.

It was in my early high school days in Centenary District, Northern Zimbabwe when I first came into contact with the Kenyan writer through his iconic novel, The River Between.

My soul was immediately touched. Our teacher of English, may his soul rest in peace, used Ngugi’s book as supplementary reading but for me, it went beyond all that.

My imagination was fired. The hills, the rivers, the elders in Ngugi’s Kenya were reminiscent of nearly everything in the northern part of my country.

My teacher held The River Between and read from it, pacing up and down the classroom. The opening chapters were especially tickling: “The two ridges lay side by side.

One was Kameno, the other was Makuyu. Between them was a valley. It was called the valley of life. Behind Kameno and Makuyu were many more valleys and ridges, lying without any discernible plan.

They were like many sleeping lions which never woke. They just slept, the big deep sleep of their Creator. ” My teacher read on, excited, “A river flowed through the valley of life.

If there had been no bush and no forest trees covering the slopes, you could have seen the river when you stood on top of either Kameno or Makuyu. Now you had to come down.

Even then you could not see the whole extent of the river as it gracefully, and without any apparent haste, wound its way down the valley. like a snake.

The river was called Honia, which meant cure, or bring back-to-life. Honia River never dried: it seemed to posses a strong will to live, scorning droughts and weather changes.

And it went on in the same way, never hurrying, never hesitating. People saw this and were happy. ” When he came to the river, my teacher’s voice became deeper: “Honia was the soul of Kameno and Makuyu.

It joined them. And men, cattle, wild beasts and trees, were all united by this life-stream. When you stood in the valley, the two ridges ceased to be sleeping lions united by their common source of life.

They became antagonists. You could tell this, not by anything tangible but by the way they faced each other, like two rivals ready to come to blows in a life and death struggle for the leadership of this isolated region.

” I felt like I was in that Kenyan terrain myself, seeing the similar valleys and ridges of our land through the classroom window.

The familiarity was exhilarating. Listening to the African Gikuyu names; Kameno and Makuyu rang a bell because Gikuyu strangely felt like Shona, my mother tongue.

My classmates and I were mesmerised too by the proverb: “Kagutui kamucii gatihakago ageni”-the oil skin of the house is not for rubbing onto the skin of strangers.

We sang out the proverb in the titillating Gikuyu in the school yard at breaktime, just for the fun of it! We were simply happy to have discovered a writer who came from a far away place that, nevertheless, felt and smelt like ours.

Little did I know that I had unconsciously been led to realise that the names of men and women in my community could also be made to appear in serious pieces of writing! I would write about my people as they are!

Apparently Ngugi looked up to Achebe. Ngugi’s actual words are, “I first met Chinua Achebe in 1961 at Makerere University in Kampala. His (Achebe’s) novel, Things Fall Apart, had come out, two years before.

” More shocking is the revelation that Ngugi was then only a second year student, almost with no published work to his name, except one story, Mugumo published in Penpoint, the literary magazine of the English Department at Makerere!

In 1961, Achebe was 31 and Ngugi only 23. We often do not notice that our heroes are people, from very humble beginnings like us. At Ngugi’s request, Achebe looked at Ngugi’s short story and Ngugi says Achebe made some encouraging remarks.

What Ngugi did not tell Achebe was that he was in the middle of his first novel for a writing competition organised by the East African Literature Bureau; a novel that would later be published as The River Between.

In The River Between, Ngugi writes about the struggles of a young leader, Waiyaki, to unite the two villages of Kameno and Makuyu through sacrifice and pain.

The novel is set during the colonial period, when white settlers arrived in Kenya’s “White Highlands” and has a mountainuos setting. Ngugi says his second encounter with Achebe was a year later at the same Makerere at the now famous 1962 conference of writers of English expression.

The African writers and critics who gathered at Makerere in Uganda in June 1962 at a conference called “A Conference of African Writers of English Expression” faced the fundamental question of determining who qualified as an African writer and what qualified as African writing.

Was African Literature only the literature produced in Africa or about Africa? Could African literature be on any subject, or must it have an African theme? Should it embrace the whole continent or south of the Sahara, or just black Africa? Should African Literature be only literature in indigenous African languages or should it include literature in Arabic, English, French, Portuguese, Afrikaans, and so on?

Ngugi says about this encounter, “My next encounter was more dramatic, for my part, at least, and would impact my life and literary career, profoundly.

” He says that Chinua Achebe was among other literary luminaries of Africa, that included Wole Soyinka, J P Clark, the late Eski’a Mphahlele, Lewis Nkosi and Bloke Modisane and others.

The East African contingent consisted of Grace Ogot, Jonathan Kariara, John Nagenda and Ngugi. Ngugi’s invitation was on the strength of his short stories published in Penpoint and in Transition.

Ngugi says Achebe was so prominent that the novel most discussed in the conference as a model of literary restraint and excellence was Things Fall Apart.

In his recent report, Carey Baraka is privileged to hear Ngugi talk about his differences with Achebe who which were based on their different sides on the language debate: “Some years later, however, the friendship between Ngũgĩ and Achebe soured as Ngũgĩ shifted towards Wali’s position on language.

In Decolonising the Mind, he included Achebe among the African writers he criticised for writing in European languages. “Achebe said English was a gift.

I disagreed,” Ngũgĩ told me. “But I wasn’t attacking him in a personal way, because I admired him as a person and as a writer, what he was doing with his novels.

I realised he was angry at me, because in the first edition of one of his books, he had quoted me at length, but in the second he removed me completely.

” But Ngugi continues to maintain his stance on the language debate: “The question of English continues to haunt Ngũgĩ.

“I can never think of my first novels without thinking of the language issue,” he told me.

“How could I have these African characters and have them all speaking perfect English?

“When I wrote my first book, I wrote it in a language my mother couldn’t access.

I rewarded her for taking me to school by writing in a language she can’t read or write. ” His voice went soft. “Maybe it’s just me. Maybe I’m just wrong about the language issue.

” He paused.

“No, I don’t think I’m wrong.

Altogether Ngugi’s sons-Tee Ngugi, Nducu wa Ngugi, Mukoma wa Ngugi and his daughter Wanjiku wa Ngugi are all published authors, showing the father’s influence on his family.

Ngugi continues to be the talking point across the African continent even in his advanced age. His never-die spirit and endurance is the other great lesson which he is giving us.

https://www.thepost.co.ls/insight/the-enduring-spirit-of-ngugi/

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press