Africa-Press – Lesotho. I came across a very fascinating journal on African literature edited by Bernth Lindfors. It puts together various presentations from the proceedings of the Symposium on Contemporary South African Literature held at the University of Texas at Austin from March 20 to 22 in 1975.

The panel called South African Fiction and Autobiography produced particularly exciting and instructive papers. Although the symposium was held way back in 1975, the statements made then are still critical to current serious scholars of South African writing produced during apartheid.

I have randomly selected passages from various presentations made by writers who have become household names in their home countries and globally. These excerpts will, no doubt, provoke the reader’s mind.

Emmanuel Obiechina, a Nigerian writer and scholar on the difference between South African writing and West African writing: I must say that South African fiction seems to me to stand at the opposite end of a spectrum from West African fiction.

The South African fiction is so different from the West African situation that each situation tends to create its own dynamic, which is reflected in the prose work produced in that area.

You can’t read the works of Alex Laguma and Chinua Achebe without being fully aware of this difference in tempo, in language and in the type of sensibilities expressed.

I think such differences are caused by the social situation. What Zeke has called the tyranny of time and place operates so strongly on the South African and so little on the West African.

Certainly anybody who reads Things Fall Apart cannot fail to be impressed by the differences between Achebe’s rhetorical resonance and the racy, vital, almost journalistic language of South African prose.

What has always intrigued me is the fact that the South African writer is the most urbanised and most deracinated of African writers, a fact which might explain the almost total urban base of his writing. This is not so in West African writing, where the writer is himself a modern product of the rural as well as the urban situation.

Ezekiel Mphahlele, a South African scholar and writer on the identity of South Africans: Since we are talking about South Africa, we need to know that we are talking about African people rather than about ethnic groups, rather than about tribes.

Many people who meet me ask me, “What tribe do you belong to?” And I get very offended. I often say, “We don’t have things like that in South Africa. ” And then they are puzzled and I say, “Well, if you want to know what language my mother tongue is, I could let you know, if it is only of importance to you.

We are all just Africans. ” In my view the word tribe does not have any meaning. If ever it had a meaning at all when it was used by the really old guard anthropologists, it referred to a group with a political organisation adequate to itself.

Today we have national governments to which all ethnic groups are answerable, so the concept of tribe, if ever it meant anything at all, does not exist. Apart from that, there are groups of people, language groups or ethnic groups. . . I don’t like talking about tribes. . . I use other words. . .

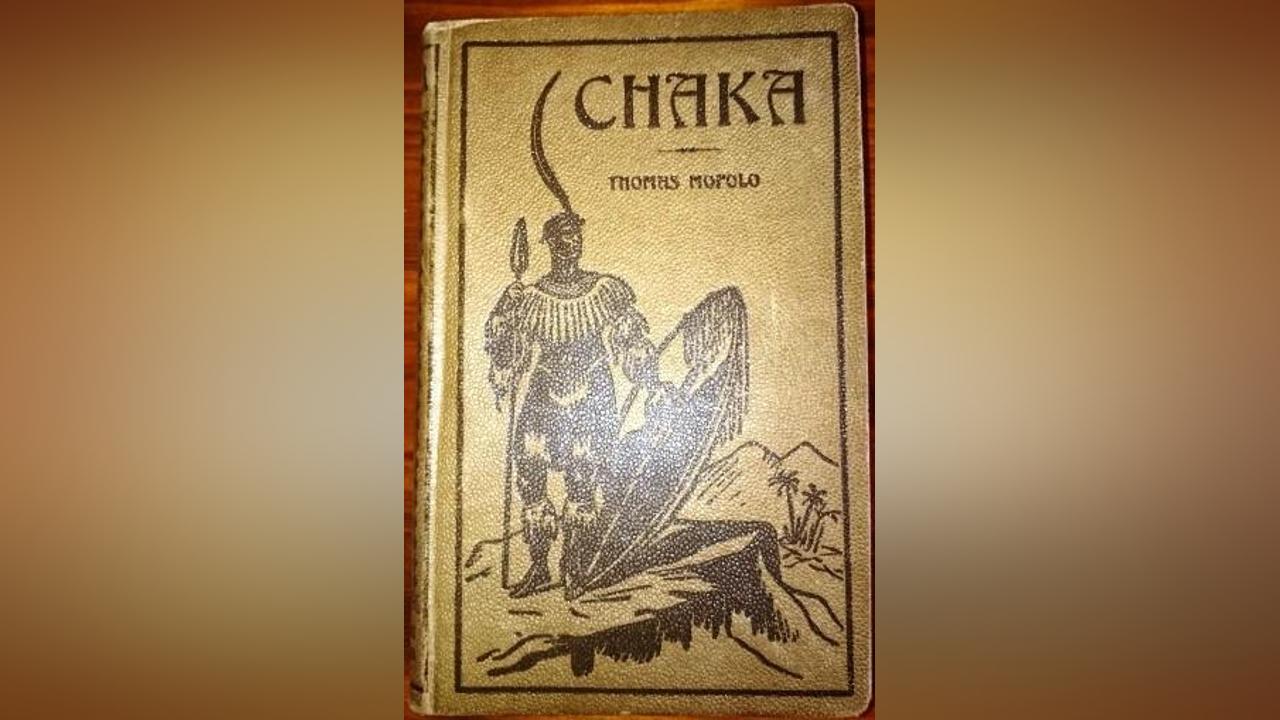

Ezekiel Mphahlele on the early black novels of South Africa: If we look at two early novels, Chaka which was written originally in Sesotho, and a subsequent novel written in English, Mhundi by Sol Plaatje, we see that these are two novels based on historical events.

There is something in them that tells us that these writers wanted to grapple with historical material because history showed the ways in which they and their whole communities had changed.

it resounds, recalling historical personalities and historical events of tremendous moment. That gives the story resonance. So is Achebe’s Arrow of God; Ezeulu’s grandeur of speech has in it an element of song.

Ezekiel Mphahlele on the latter day South African novel: My point is that we find resonance in these two early South African novels, Chaka and Mhundi, in a way that we do not find it in South African novels today (the 1970’s).

There is a different kind of sound in contemporary South African fiction. The reason is this: when you get to Alex Laguma, Peter Abrahams and writers like Bloke Modisane, the field narrows down to a single melody.

The orchestration of the novel is more in visual terms. Look at any of Laguma’s novels and you will find an impressionistic cluster of things that you see and feel.

A single melody is brought about by the fact that one is constrained to give definition to the physical and mental agony of a man in a situation like the South Africa one, where a common event might be a criminal offence, a chase, a shooting, an arrest, or a hanging.

This is what narrows it down to the single melody. The novel in South Africa almost becomes a long short story because it is so compact. It seems like the counterpart of a poem in prose because it has a singleness of melody, a singleness of point.

It does not sprawl all over; it works in flashes. Just a flash here and there will illuminate the truth. This is how it approximates the poem so much.

The South African novel will work that way. There is always the inevitability at the end.

The choices are few because the society is what it is. If there are no choices in a society, the fiction will represent that, will show that. If you have a small minded people such as the Boers, the fiction will never be big.

It’s small; it’s tiny; it’s parochial; it’s way down at the bottom; it has never grown up, never matured because the people are small minded — they’ve all got blinkers on their faces.

How can you expect any broad vision from people like that. . . Ezekiel Mphahlele on black and white relations in South Africa: There is a big barrier between us (blacks) and the whites.

We are looking at each other through a keyhole all the time. I don’t want to write about white people because I don’t know them that well. If I write about them at all, it’s as adults, because I know them as adults and I don’t know them as young people.

I only see their children playing around in the park; when I was a boy, I saw them riding around on their tricycles or motor cycles in the streets. I don’t know how they are born.

I don’t know how they grow up in their homes. I don’t know how white people get married except what I see in the movies or what I read in books. I don’t know how they court, or how they make love.

.

. If you are born in South Africa, you never forget you are black. Nobody ever lets you forget you are black. You have these pressures on you day after day. You are harassed.

You come back to your ghetto life exhausted, and you may take it out on your children or your family or you may not, but there is always this constant fight for survival.

Peter Nazareth, Ugandan writer and academic’s responds to Ezekiel Mphahlele’s views on South African Lit: First of all, I don’t think it is completely correct to say that there is no music in South African writing.

Rather, we should say it is not the kind of music we like to listen to. You have the music of sirens, knuckles, and boots, and you have heard it coming through South African writing for a long, long time.

While some of us were emerging from colonial rule in east and West Africa and going through this process. . . When we looked at South African writing, we found that it was dealing with a specific situation and yet raising issues which came to confront us later and still confront us today.

Peter Nazareth on South African Literature and setting: First, the question of setting. Do you deal with your immediate environment or do you try and escape it and deal with man?

It is quite clear the answer is that you can only be universal by being very specific. Peter Nazareth on South African literature and language: Then allied to the question of setting was the problem of language.

How do you deal with a violent situation and yet create a language to communicate that violence in art? In other words, you have the reality which is violent, but the language itself has to come to grips with it.

Some of the solutions that were found to this language problem were remarkable. For example, Alex Laguma writes in a style that looks very journalistic, but actually he selects details very carefully and has a kind of counterpoint underneath.

For instance the ubiquitous cockroach in A Walk in the Night. When the cockroach comes to perform his act again, as the rat does in in one of Richard Wright’s novels, it is not journalistic anymore.

It carries a significance, and it carries a sense of violence as well because when you stamp on a cockroach, you are stamping on something that has found a way of surviving.

Peter Nazareth on the question of the individual and the community in South African literature: As I said, in East Africa we were being told that you had to deal with the individual, but here was South African writing insistently dealing with the community, because under this system of extreme oppression, people could only survive as a community.

They suffered as a community and they could only endure their suffering as a community. When you look at the best of South African writing, you find a dialectic process: you find oppression ramming people down, seeking to dehumanise them and actually dehumanising some, but then you find the counterforce of the community still surviving in spite of everything.

It is a kind of dialectic force. Here again was a lesson for us: the writer should not be concerned only with the individual, he should be concerned with the whole community and its problems of survival.

Mongane Wale Serote, South African poet on the writing environment in South Africa during apartheid: The only way I can describe black South African writing is to say it is a very tragic thing in its own way because of what is happening in South Africa.

The writing seems to have no continuity; usually when we talk about black South African writing, we start around the 60s, but I think it started long before then.

.

. When I started writing, it was as if there had never been writers before in my country. By the time I learnt to write, many people – Zeke, Kgositsile, Mazisi Kunene, Denis Brutus — had left the country and were living in exile.

We could not read what they had written, so it was as if we were starting from the beginning. Oswald Mtshali, a South African poet on what he terms his level of South African literature: A black man’s life in South Africa is an endless series of poems of humour, bitterness, hatred, love, hope despair and death.

His is a poetic existence shaped by the harsh realities and euphoric fantasies that surround him. Every day is a challenge in survival not only in the physical sense but also spiritually, mentally and otherwise.

It is hard for people who live in “free societies” to comprehend a black man’s life in this strange society. If you do not share my environment and my culture, it is hard to understand what I am talking about.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press