Africa-Press – Liberia. Liberia may finally be in a position to reclaim what policy analysts are calling “the years that the locusts have eaten,” as new economic data reveals the staggering scale of revenue the country has lost under ArcelorMittal Liberia’s near-exclusive control of the Yekepa–Buchanan railway.

With President Joseph Nyuma Boakai, Sr. having returned the company’s Third Amendment to the Inter-Ministerial Concessions Committee (IMCC) for renegotiation, the nation finds itself at a critical decision: continue a two-decade-old monopoly model or embrace the multi-user rail system that experts say could transform Liberia’s economic future.

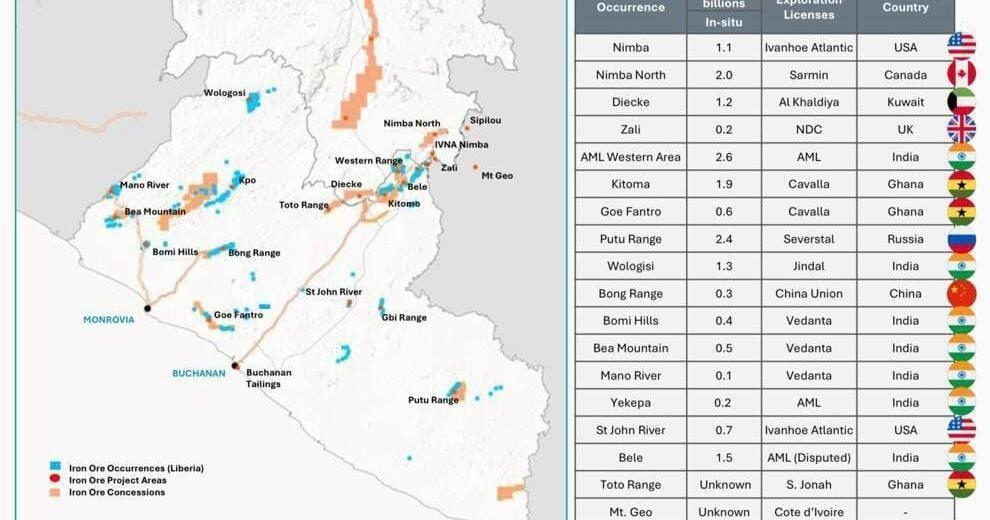

For nearly 20 years, the rail has operated as a bottleneck. Geological surveys show Liberia holds more than 17 billion tons of iron ore, with an estimated 12 billion tons located along or near the Yekepa–Buchanan corridor. Roughly 9 billion tons of high-grade ore in northern Nimba remains stranded—not because the deposits lack investors, but because other operators cannot gain predictable access to the rail.

As one mining executive told the Daily Observer last year, “Liberia is sitting on a mountain of ore, but we cannot move a single ton without credible rail access. Every year of delay is a year of revenue gone forever.”

Senator Amara M. Konneh’s recent breakdown of the Ivanhoe Atlantic access framework has provided the clearest benchmark yet of the corridor’s potential value. According to his analysis, the combined Product Access Fee and Cross-Border Transit Fee under the Ivanhoe framework ranges from US$2.05 to US$1.65 per ton, depending on transported volume. Applied to the 9 billion tons across multiple licenses in northern Nimba alone, this yields between US$14.8 billion and US$18.4 billion in long-term revenue—translating to US$594 million to US$738 million per year over 25 years.

These figures cover only rail access fees. They do not include royalties, corporate taxes, port charges, or the substantial capital spending and job creation that accompany new mining operations.

By contrast, AML’s fiscal contribution over almost two decades — including royalties and taxes — appears to total under US$700 million. In its 2023 Annual Report, AML also reported revenue losses due to derailments along the very corridor it seeks expanded control over, raising questions about operational efficiency under a monopoly model.

Lawmakers have long raised concerns about AML’s control. In a 2022 hearing, then-Representative Clarence Massaquoi remarked, “The rail is a national asset, not a private driveway. Liberia cannot allow one company to determine the economic direction of an entire region.”

Civil society organizations have echoed those concerns. In an earlier statement, the Institute for Research and Democratic Development (IREDD) warned that “monopoly control over public infrastructure undermines competitiveness and denies the country the full benefits of its own resources.”

The Third Amendment has now been returned to the IMCC twice. In 2021, it was rejected by the Legislature — not the Executive — over concerns ranging from capacity monopolization to clauses that risked placing the agreement’s provisions above Liberian law. Former Senate Concessions Chair, Senator Henrique Tokpa, stated at the time, “We cannot endorse any agreement that ties the government’s hands. Concessions must align with national interest, not supersede it.”

The Boakai Administration’s decision to send the amendment back has re-energized discussions about the kind of rail governance model Liberia needs. Policy analyst Abraham Kromah captured the sentiment earlier this week:

“The data is now clear. The value of the corridor is in throughput revenue, not one-off bonuses. Multi-user access could generate more for Liberia in two years than AML has paid in nearly twenty.”

Whether these new revelations mark a turning point depends on the renegotiation now underway. For the first time, Liberia has concrete numbers quantifying the scale of opportunity lost — and the scale that could still be recovered.

As the IMCC revisits the AML proposal, the central question is whether Liberia will continue the patterns of the past or finally adopt the rail model that industry experts say can restore decades of foregone revenue and unlock long-delayed national development.

Source: Liberianobserver

For More News And Analysis About Liberia Follow Africa-Press