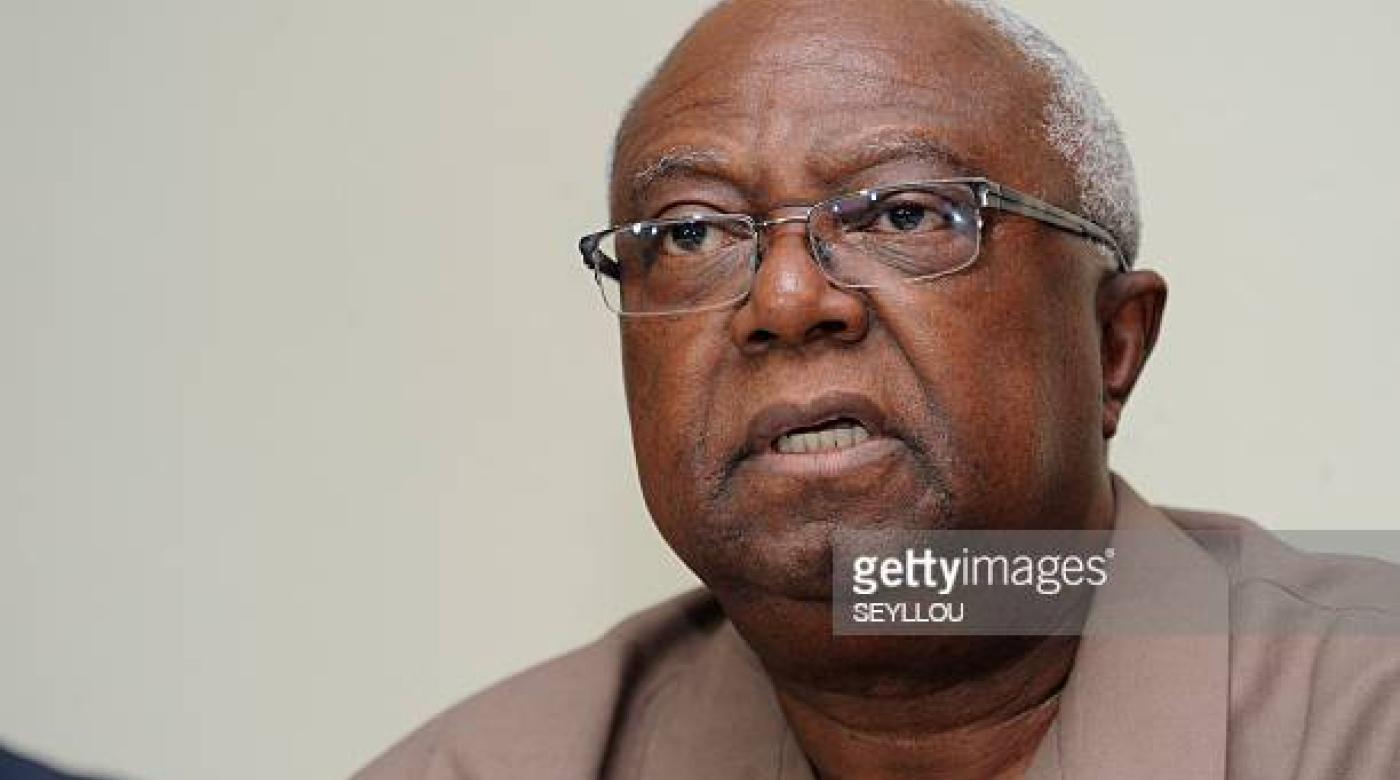

Africa-Press – Liberia. Lamini A Waritay was Minister of Information in the war-time IGNU headed by Dr. Samos C. Sawyer. He also served first, as Secretary-General, and later as President of the Press Union of Liberia during the tumultuous political period of the Samuel K. Doe regime. He and the late Prof. T. Nelson Williams started the department of Mass Communication at the University of Liberia, and at one time headed the department himself after the first chairman, T-Nelson Williams, had left in the wake of the 1984 invasion of UL main campus.

Dr. Amos Claudius Sawyer had been a household name long before I first met with him in his office at the University of Liberia, few weeks after the coup in 1980. In addition to being well known as an activist and an erudite political science professor, Dr. Sawyer was also widely acknowledged as one of the architects behind the formations of MOJA (Movement for Justice in Africa), and, subsequently, the center-left-leaning Liberia People’s Party (LPP).

He had also by then attracted international attention on account of the near-epochal mayoral race between him and his opponent, ChuChu Horton—who was the candidate put up by the ruling True Whig Party. Sawyer’s desire to get into the race was less about landing a mayoral job than about testing the political waters under the monolithic Grand Old TWP.

In the wake of the cataclysmic but widely popular coup d’état carried out by non-commissioned personnel of the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) in the early hours of April 12 1980, I went to interview Dr. Sawyer on the dramatic if bloody demise of the TWP regime that had hitherto monopolized the levers of power for 133 years. I was then a very young staff writer of the government-owned newspaper, the New Liberian.That first meeting with the professor didn’t go quite well initially. Once he realized I was from the Government-controlled newspaper, he unbundled his mind on, and registered his displeasure over the editorial bent of the paper. He accused the paper of giving more coverage to the campaign of his TWP opponent than to his.

Ordinarily, an opposition candidate would care less about getting his/her electoral activities covered by a government-controlled media outlet. But I understood the context of the learned professor’s displeasure, considering that in those TWP days privately-owned media channels were not only virtually non-existent, but where they did, they were very much inconsequential. Under such circumstances therefore, the New Liberian became the most widely-read and circulated paper. Its electronic or broadcast version, the government-controlled ELBC Radio, was also the most listened to, with a reach that went far beyond the borders of Liberia. This state of affairs was thus clearly disadvantageous to the political and electoral interests of the opposition at that point in time.

And so cognizant of the political and media backdrop against which Dr. Sawyer was venting his frustration, I sat there quietly listening to him until he had exhausted his points. I then acknowledged his right to feel aggrieved over the short shrift his campaign had been given by the government media during the pre-coup mayoral race. I however managed to draw his attention to individual actions undertaken by some staff members of the New Liberian to carve out a niche for some level degree of independent expression in the paper.

In particular, I referenced the trenchant views and muscular editorials the irrepressible Rufus Darpoh and I regularly expressed in the paper—some of which routinely triggered the ire of overzealous government officials who often wondered whether we were running a privately-owned newspaper under the roof of the Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism (MICAT).

I cited a weekly column I wrote in the paper under the title, Waritay’s Diary—which provided me a platform to independently and energetically discuss issues of national concern. I cited to the Professor a particular high-stake commentary I had written which, under a less liberal President than President William R. Tolbert, Jr. could have, at best, cost me my job, and at worst, landed me behind bars. It had to do with the detention of Baccus Mathews and his colleagues for allegedly wanting to overthrow the government, and the subsequent strong rumors circulating to the effect that President Tolbert was planning to execute all of them in short order. The article was published at a time when the entire nation waited with bated breath for the president to return from a scheduled meeting of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Zimbabwe, at which time, it was rumored, he would order the executions. Noticing that no one was taking any risk of discussing the issue of the political detainees, I decided to weigh in on the subject in a limited but very public way—by calling on President Tolbert to exercise restraint and patience in regard to the detainees, and urging him to forgive them, and even have them released as an act of magnanimity. After all, I argued, they were all young people, and therefore may have been carried away by youthful exuberance.

My write-up may not have had any impact on the relatively reformist President Tolbert. In any case there was no time during which I could have gauged the degree to which my column that week may have influenced him one way or the other, because the issue was rendered moot by the coup that took place not too long after that publication. Some political analysts later suggested that the execution rumors constituted the proximate cause of president Tolbert’s brutal assassination and the accompanying overthrow of the government. They postulated that many of the non-commissioned soldiers who carried out the coup had ethnic affiliation with one of the prominent detainees, Dr. George Boley, and therefore felt they couldn’t stand idly by while one of their kinsmen was left to die by the hangman’s noose.

Amateurish Arsonist

I recounted those episodes to Dr. Sawyer so that he would understand that despite being a government-sponsored newspaper, Darpoh and I tried in our little way to liberalize the content of The New Liberian. My end goal was to have the university don become comfortable with me, and encourage him to grant me the exclusive interview. The professor may have been left unconvinced of where I stood politically, but he ultimately relaxed and let me proceed with the interview.

Following that first personal encounter with him, Dr. Sawyer and I seemed to have opened up a new chapter in our interactions going forward. I recall how, when I returned from graduate studies at Boston University, three years after the interview with him, Dr. Sawyer had green-lighted my hiring in the newly established Mass Communication department on the recommendation of the late Prof. T. Nelson Williams, the first Chairman of the department. That was when Dr. sawyer held the position of Dean of the College of Social Sciences at the University.

Years and decades later, Dr. sawyer and I had several more encounters; too many to recall all in this piece, but a few stood out to warrant brief mentions—especially now that our paths will never cross again on earth as his own life’s sojourn has ended.

One such interaction was when an amateurish arsonist (reportedly a paid agent or supporter of the Doe regime) had attempted to set his modest Caldwell home ablaze. Several months before that incident, Dr. Sawyer had been incarcerated at the post stockade prison. The regime had framed his detention as an accountability issue emanating from his chairmanship of the Constitutional Review Commission. But some political analysts knew better than accepting such a spurious excuse for his detention. His only sin was that he had the temerity to call on the military leader to resign the presidency if Doe wanted to run in the first multi-party elections that had been set for October 15, 1985. That way, Dr. sawyer had argued, there would be a level-playing field for all presidential hopefuls.

Other political observers knew also that Dr. Sawyer had spurned Samuel Doe’s request to have the professor as his running mate. The situation between Doe and Sawyer had developed into a case of a jilted admirer—Doe being the one left at the short end of the stick in the bargain.

When I visited his house on the morning after the arson attempt. His dutiful wife, Comfort Sawyer, was there with him. I had made sure I took along veteran photographer, Sando Moore, to take some pictures of the attempted arson. I remember Dr. Sawyer quietly, and with no expressed anger, narrating what had happened. But through it all he never came across as being afraid or intimidated by that cowardly act. He seemed more concerned about the safety of his family than about himself.

Little did he know that I had planned to amplify the incident by weaving it into a piece I was already working on for the London-based weekly West Africa magazine regarding the Doe regime’s assault on the University of Liberia–including the bloody invasion of the UL main campus on August 12, 1984, during which students agitating for the release of Dr. Sawyer from detention were brutally attacked by security personnel on the expressed instructions of Doe himself. The magazine published the story and later a picture of the arson attempt on Dr. Sawyer’s house.

Carrying the headline, University Under Threat, I highlighted the regime’s clampdown on the University, citing harassment and imprisonment of its staff and student activists—all in an attempt to silence any opposition outlet in the lead-up to the first democratic elections in the country’s history. I likened the situation at UL to the fate of Makerere University when that once prestigious university was under the heels of Uganda’s impulsive and dictatorial military strongman, Idi Amin.

Sources at the NSA subsequently hinted me that the article so ruffled President Doe that he threatened to “bury alive the author” of that article if and whenever his or her identity became known to him (who said life was easy for media personnel in Liberia during the struggle to cultivate and entrench media freedom and political liberalism especially under a military dictatorship). Because of the repressive media environment then, all articles I wrote for West Africa magazine were by-lined “From a Special Correspondent”.

The alarm set off by the publication eventually contributed to a series of visits to Liberia by foreign correspondents, including the veteran Editor-in-Chief of West Africa magazine, Kaye Whiteman. Once he was in the city, I got him to visit Sawyer and had him interviewed. Sources at the NSA again got me to know later that Kaye and I were being surveilled throughout his stay in the country, including during our Caldwell visit to see Sawyer. I didn’t disclose this piece of information to Kaye, so as not to arouse his fears. I was less concerned about the surveillance, as that kind of harassment had since become part of my life during my activist days—especially during my presidency of the Press Union of Liberia, while I taught at the university at the same time.

Of all my interactions with Dr. Sawyer, none, however, brought me much closer to him and therefore afforded me a better opportunity to know him more deeply than when I served as IGNU’s Minister of Information. —from 1991- to 1994. It was during this period I got to know how courageous, brainy, level-headed, enlightened, tolerant, humble, and fiercely patriotic a Liberian he was, and how very much open-minded he was–even to a fault.

Becoming his Minister was almost fortuitous for me. I had no wish participating in the interim government that was established in Banjul, The Gambia, by representatives of seven political parties and eleven civil society groups at the behest of the West African regional bloc (ECOMOG) in 1990. And so, after representing the Press Union (as one of the civil society groups invited to the Banjul meeting), I made plans to depart Banjul.

Somehow Dr. Sawyer got wind of my exit plan, and wasted no time in summoning me to his hotel room at the ostentatious Kairaba Hotel, to discuss “the rumor” of my imminent departure. I confirmed to him that yes, indeed, I was poised to depart Banjul in a day or two. He seemed to have been taken aback by my planned move, wondering how I could think of walking away even before a framework for a fully-fledged transitional government had been put in place. He then disclosed to me that he intended to entrust me with the responsibility of propelling the media and communications aspects of the interim government.

In response, I assured him that if he was looking for a “very good” Minster of information, I would suggest some names in this regard. I then proceeded to naming Kenneth Y. Best, Rufus Darpoh, Tom Kamara, and Weade Kobbah-Wureh as quite capable persons who would fit the bill. The newly minted IGNU head acknowledged the competency of all those I had named, but insisted that he and some other civil society representatives at the conference had settled on me as the person to take charge of the IGNU’s information and communications activities.

Tried as I did to wiggle out of the situation, the Prof. remained steadfast. And so even after I subsequently left Banjul some weeks later and returned to Freetown where I was based before attending the conference, hoping that someone else would be designated for the job in my absence, Dr. Sawyer sent Tom Kamara (who was himself making a quick trip to Freetown at the time) to fetch and bring me along with him to Banjul.

And return I did, with one of my first assignments being to secure a BBC Focus on Africa interview for Prince Johnson’s delegates to the Banjul conference, during which they declared their support for the IGNU—to the discomfiture of the NPFL which had ignored a regional invitation to attend the Banjul conference.

Working closely with Dr. Sawyer was indeed a rewarding opportunity. His brilliance illuminated every discussion and strategy session he and I routinely had on political and communications issues. And he too, in the fullness of time, seemed to have relished the writing, verbal and other information/communication capabilities I brought to bear on my assignment—as reflected in the write-ups and publications he and I co-authored, and the almost interminable interview sessions I had with international media outlets, including the BBC, CNN, VOA and Radio Deutsche Welle

Our synergistic working relationship and mutual respect got to a point where, given the pitched propaganda brattles that were ongoing between the IGNU and the NPFL, I became, almost on a daily basis, the first official of government to be summoned to see him in the morning, and the last to see him before he retired for the night. We were constantly strategizing to stay ahead of the curve with regard to NPFL’s well-oiled propaganda machine.

During the early days of the IGNU, and after jointly working on a publication on the rationale of the IGNU (for the purpose of creating national as well as international awareness), which I printed in Accra, Dr. Sawyer remarked that he felt sorry for me, because my task had become all the more challenging not only because of the nature of my job during war-time, but because he was himself no stranger to my area of discipline. In fact, he had some media background himself, and therefore striving to satisfy him with my work was not an easy task. And boy oh boy, Dr. Sawyer was a writer and analyst per excellence. One only need to read his several books, scholarly articles and monographs he produced in his lifetime to notice and enjoy the way he had with words.

Drafting a speech or related material for Dr. Sawyer and not expect him to edit it with the thoroughness of a fine toothcomb could turn out to be merely inspirational. Thankfully, we understood each other’s writing style so much so that we often spent less time finalizing a given draft. And we would high five each other after we had been satisfied that what we had ultimately produced was of a stellar quality.

I also learned from my interactions with the late author that mutual trust and frank exchange of views on pertinent issues (devoid of sycophantic and fawning accolades) constitute indispensable elements in fostering a good, smooth, honest and productive working relationship between a minister of information and his boss. That was what characterized our working relationship, and engendered mutual respect and trust to the point where he made sure I was part of many delegations sent out of the country to advance the peace process.

One such instance was when he sent me on a two-man delegation (headed by Foreign Minister Baccus Mathews) to Nigeria to hold talks with the military strongman, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, in the wake of NPFL’s ‘Octopus’ blitz on Monrovia in October 1992. That Abuja emergency meeting with general Babangida marked the beginning of the degradation of NPFL’s war efforts and capability.

Consensus Builder

I have observed at close range, and worked with three Heads of State of Liberia in various positions. And therefore, believe me when I say I found Dr. Sawyer to be the most patient, empathetic and clear-headed of all. His penchant for consensus building was unrivalled. When Dr. Sawyer convened a cabinet meeting, he would sit there for hours listening with rapt attention while taking copious notes as he went around the table of ministers, advisers, and other cabinet-rank officials soliciting their views on major policy decisions. It was only after hearing out all those with views and suggestions that Dr. Sawyer would summarize inputs of hours-long discussions, and synthesize them in such a way that everybody felt good that his/her contribution had been considered in reaching a cabinet decision. Yes, despite his massive intellect, and never mind him being the chair of the meeting, he never pretended that he knew it all.

I am not sure whether it was the upbringing he had from his devout Catholic father (the late Abel Sawyer) that got Dr. Sawyer to be so trustful and open-minded to the point of gullibility—a trait that got him in my crosshairs on two occasions. He believed in the redemptive capacity of the human spirit, and therefore always endeavored to see the best in everybody, including those who betrayed him or conspired against his political interests. That disposition perhaps explained why he seemed to have misread what was obviously Charles Taylor’s strategic endgame of wanting to capture Monrovia, the seat of the IGNU and the location of the ECOMOG base.

Time after time I tried to convince the professor that while Taylor was engaged in a game of smoke and mirrors during the tortuous peace process, the NPFL’s charismatic and cunning leader all along had his eyes firmly set on the big price of taking over Monrovia by force one day—to hell with the presence of ECOMOG forces. But Mr. interim President could not bring himself to accept that Taylor would be so daring and reckless as to engage the heavily armed peace keeping force in an open combat in the streets of the densely -populated city. And when I told him that I had been thinking so much about that possibility to the extent where I had had a nightmarish dream that the city was under heavy attack, Dr. Sawyer laughed and jokingly called me “Joseph the dreamer”.

The last time I raised that possibility with him again was after an interview session a visiting foreign television crew had conducted with him at the Executive Mansion, during which, interestingly, the same fear of an NPFL attack on Monrovia was expressed by one of the crew members. Dr. Sawyer, the ever-optimistic professor, told the TV crew that it would be a tall order for Taylor to pull off such a stunt on heavily protected Monrovia. Shortly after the interview, I got on his case again on being a bit naïve (with due respect to him) about what Taylor was capable of doing. I told him that he should have responded to that particular question by issuing a strong warning to Taylor against embarking on such a reckless misadventure, as it would herald his demise.

Less than two and a half months after that Executive Mansion conversation, and while war-weary residents of Monrovia slept, Taylor rolled the dice on IGNU and ECOMOG, by launching his ‘Octopus’ campaign to capture Monrovia. It was the most ferocious and audacious attack on ECOMOG since the peacekeeping outfit landed in the country two years earlier– Taylor threw everything (sink and all) at ECOMOG and the densely populated city, and almost captured the ECOMOG base on Bushrod Island. It was a dare devil and kamikaze-like offensive residents of Monrovia and its environs at the time will never forget in a hurry.

As fate would have it, it fell on the shoulders of the “Joseph the dreamer” (along with foreign minister Baccus Mathews), to go and wake Dr. sawyer up around 1.00.a.m on October 15, 1992, to give him the bad news of the NPFL’s assault on the city. Without saying anything, he looked at me in a rather crestfallen way, and I knew at that point that he must have felt like telling me: “You told me so, Lamini.” But of course, that was no time for a blame game.

With pitched battles raging between the marauding NPFL fighters on the one hand, and ECOMOG, Black Beret, ULIMO and remnants of battle-hardened AFL forces on the other, and with rockets being directed at Ducor Hotel itself, courtesy of NPFL’s rocket woman, Martina Johnson, the U.S. embassy offered to evacuate Dr. Sawyer and his immediate family members to safety. He refused to take the offer, insisting that his life and those of his family were no better than the lives of Liberians he would be leaving behind to be slaughtered in the event NPFL overcame ECOMOG and allied forces.

That experience with Taylor apparently still didn’t convince Dr. Sawyer to lose faith in Taylor as someone to do business with in the pursuit of peace. And so it was that one year after ‘Octopus’, professor Sawyer again induced my angst over his reported agreement to meet with Taylor somewhere at Firestone for a purported peace meeting that was being organized by some prelates and women’s groups.

Fearing that the IGNU leader, who was not often known for saying “no” to people, might just fall prey to the exhortations of these well-intentioned but rather naïve religious and women’s groups, and undertake the road trip to meet Taylor and his generals at Firestone, some worried IGNU officials got in touch with me to help dissuade the professor from doing so.

By then I was in Abidjan on my way to Paris, France, where I had an international media conference scheduled a few days hence. Thankfully, I had remained in contact with one or two colleagues who knew the hotel I had checked in once I had arrived in Abidjan. They called me and briefed me on what was happening up at Ducor. They left me in no doubt that we were staring at an apocalyptic scenario waiting to happen.

I wasted no time in calling the president’s landline (Mobile phones were not in style then). He asked me whether I was okay and when my flight was scheduled to depart. I told him I was not doing fine at all if what I was hearing from Monrovia was anything to go by. When I got to the kernel of the issue at hand, he tried to sweet-talk me with his very lively and infectious laughter, saying “Oh no worries, Lamini; everything should be ok…” At that point, I couldn’t hide my exasperation that he could even entertain such a risky idea of going to meet the hungry lion in his lair just because we had become so desperate for peace that we were ready to catch any straw, no matter what! I then proceeded to calmly but deliberately let him know, that should he embark on what I regarded as a suicidal mission, he will certainly hear about my resignation as his Minister of Information on the BBC even before he got to Taylor. I noticed a brief silence at his end of the line, only for him to come on again to say “No worries, Lamini; all shall be well.” He then wished me a safe trip. I was not bluffing. I meant it. And he knew that I was dead serious at that point.

Kill List

A few years later, after the election of Charles Taylor in 1997, someone in the inner circle of the NPFL leader at the time, revealed that indeed a plan had been hatched to decapitate the IGNU leadership which, along with ECOMOG forces, stood in Taylor’s way to the Mansion. Sawyer and his delegation’s trip to the proposed Firestone meeting would have offered an excellent opportunity to achieve this nefarious goal. As per the plan, Dr. Sawyer and his entourage were to be ambushed and slain even before they reached the Firestone rendezvous. In the ensuing chaos, the NPFL would again launch another do-or-die attempt at taking over the government in Monrovia.

The innate goodness of Dr. Sawyer often radiated in his manifest sense of empathy. I recall how deeply pained he felt after seeing a kill list the NPFL had drawn up, on which my name was at number 20 out of 46 persons listed—including, of course, Dr. Sawyer himself. (Dr. H. Boima Fahnbulleh, Kofi Woods, Commany B. Wisseh, Alaric Togba, Dr. George S. Boley, Kabineh Janneh, Harry Yuan and Brownie Samukai were all on the hit list, which can be found using the Google search engine). Taylor had reportedly set up an assassination squad to track down and eliminate all those he deemed to be inimical to his chances of becoming president.

Dr. Sawyer became even more alarmed about my safety after learning about an alleged assassination attempt on my person while attending a conference of Ecowas Ministers of Information along with my two delegation members (Prof. Weade Kobbah-Wureh, now Vice President of Administration at UL, and the late Jeff Mutada).

It was these two Liberian delegates who first alerted me (at the tail end of the two-day conference), that they had been told quietly by some Nigerian authorities that the car assigned to me for the duration of the conference had blown up while the unsuspecting driver had gone to wash it. They said their official informants had concluded that said car had in fact been bobby-trapped to cause maximum damage to the occupants. If I can recall correctly, Mrs. Kobbah-Wreh (still alive) and Jeff Mutada (long dead), had been advised not to let me be immediately informed about the incident, lest I got distracted at the conference.

They told me also that the first driver who had been assigned to the car was killed in the explosion. I suggested that we should go see the family of the deceased and sympathize with them, but I was dissuaded from doing so for “security reasons.”

Dr. Sawyer got a chilling confirmation of this reported assassination plan from University of Liberia former Dean of the Louis Arthur Grimes School of Law, professor and former Judge, Mrs. Luvenia V. Ash-Thompson (who is also still alive as far as I know), who narrated at a cabinet meeting an encounter she had previously had with some NPFL-affiliated individuals in Abidjan, while she was briefly passing through La Cote D’Ivoire—which had become a nest for NPFL officials. (Judge Ash-Thompson was one of Sawyer’s advisers with cabinet rank, and so attended cabinet meetings). She disclosed at the meeting that some NPFL operatives had boasted to her that by the time she got back to Monrovia, the IGNU’s Minister of information would have been “no more”, as they would have eliminated him.

The Judge said she didn’t take them seriously, because as far as she was concerned, before she had left to go on her trip, I was still in ECOMOG-fortified Monrovia, and so couldn’t understand what the guys were saying about my possible demise. What the judge didn’t know at the time though, was that I had left for Nigeria, where Charles Taylor’s benefactor, General Sani Abacha, had since carried out a palace coup and taken over the reins of government in that country (Former President, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, who had given his unflinching support to ECOMOG and the IGNU while he was at the helm of government in Nigeria, had by then since relinquished power).

I never tried to verify or follow up on these reports of an assassination plan against me in Nigeria. I had relied solely on what my colleagues had told me in a hush-hush manner, but after Judge Thompson had narrated her own experience in Abidjan, Dr. Sawyer and I concluded that it was not a joke. He instructed relevant security personnel to ratchet up my security—something I wiggled out of, as I have never felt comfortable with being guarded by gun-toting men.

Noticing how rattled he had become over my safety, I constantly assured the interim president that if I survived Master-Sergeant Doe’s threats and close calls I had with his regime, I would survive Taylor’s as well. Above all, I said, as long as I was at peace with my conscience over what I was doing in pursuit of a democratic society, I was not too bothered about the consequences.

Truth be said, I had no incontrovertible evidence that Taylor personally planned or may have orchestrated the reported attempt on my life, or that the list itself was authentic, but some security officers were convinced that the list was for real, and that someone who was in Taylor’s circle, and who had disagreed with the assassination approach, had in fact leaked the information.

Dr. Sawyer took it seriously after he recalled a comment Taylor’s ‘Minister of Defense’, Tom Woewiyu (now deceased), once made to him at one of the dozens of regional peace conferences held on Liberia. After Dr. Sawyer had told Tom Woewiyu that unlike the NPFL, the IGNU had no army of its own, Woewiyu retorted that “you don’t have an army, but your IGNU minister of information is like a “one-man army” against the NPFL by way of his masterclass “propaganda” skills.

What Tom Woewiyu didn’t also tell Dr. Sawyer was that his NPFL chieftain. Charles Ghankay Taylor, was more adept at propaganda and smooth talking than anyone else—a capability that he used to the utmost to dazzle his BBC audiences around the world, and bamboozle the likes of former president Jimmy Carter into influencing regional leaders to agree a reduction in ECOMOG forces in Liberia, and the simultaneous withdrawal of heavy weapons—while he surreptitiously planned his ‘Octopus’ offensive against Monrovia.

Indeed, Dr. Sawyer’s concern over my wellbeing had become such that when I got knocked out by a bout of malaria at the mosquito and rat-infested Ducor Hotel, which became our residence for the duration of the IGNU, he not only ensured that I was treated by his personal physician, but also made a point of it to deploy a bevy of SSS personnel and ECOMOG soldiers at the Japanese Maternity block of the JFK hospital where I was admitted—with restrict instructions to have only limited access to me by relatives and friends. I spent only two nights there, with the rest of my recovery time spent on the same floor at Ducor that Dr. Sawyer had his suite.

That was the empathetic boss I knew and worked with. That was the man who could sniff competence and efficiency from a distance. And that was the consensus builder who, despite his academic laurels, scholarly discipline and international standing, was nevertheless always keen on listening to even the dim-witted. He loved politics, but not for politics sake, but rather how politics and political power can be leveraged for the good of the people—rather than for vainglorious and self-seeking purposes, as has become all too evident in post-war Liberia.

For More News And Analysis About Liberia Follow Africa-Press