Africa-Press – Liberia. Liberia witnessed a spiral of violence, hunger and death for more than a decade when the country’s women said enough was enough and united to end the war. They came together regardless of their origin, class or religion.

Cecelia Danuweli was one of these women who began by denying their husbands sex and ended up redefining the frontline of a brutal civil war. She is part of the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET).

Liberia witnessed a spiral of violence, hunger and death for more than a decade when the country’s women said enough was enough and united to end the war. They came together regardless of their origin, class or religion.

Cecelia Danuweli was one of these women who began by denying their husbands sex and ended up redefining the frontline of a brutal civil war. She is part of the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET).

An award she shared with another extraordinary Liberian woman: Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first elected female head of state in Africa and president of Liberia from 2005 and 2018.

“Leymah, you are a peacemaker. You had the courage to mobilise the women of Liberia to take back their country”, said Sirleaf in part of her acceptance speech dedicated to her fellow countrywoman Leymah Gbowee. “You redefined the frontline of a brutal civil conflict – women dressed in white, demonstrating in the streets – a barrier no warlord was brave enough to cross.”

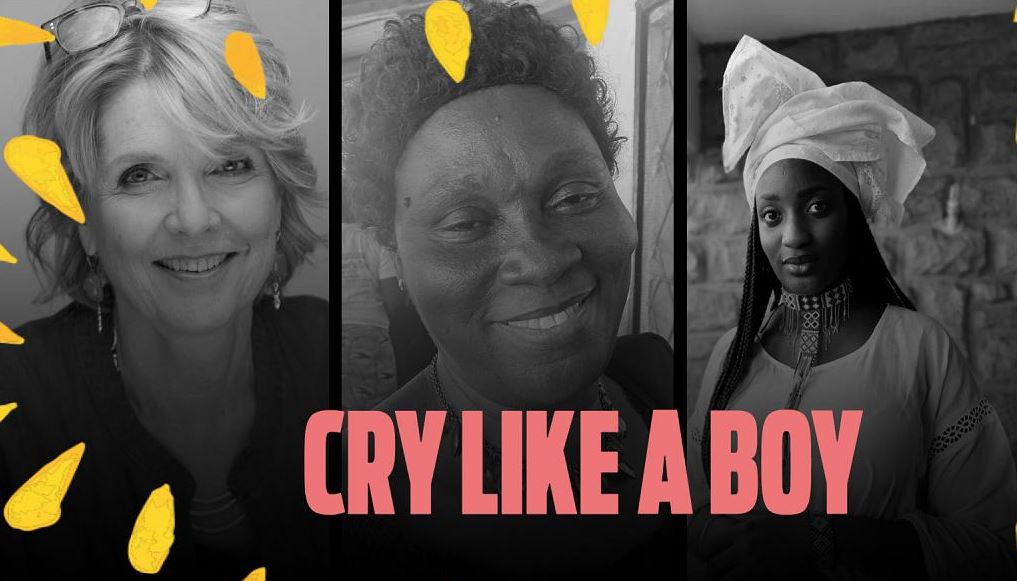

Award-winning director Gini Reticker travelled to Monrovia to tell the story of these women and she did so in the 2008 documentary Pray the Devil Back to Hell. Reticker was captivated not only by the courage and determination of these women but by the epic and exceptional nature of their story. In this episode of Cry Like a Boy, Cecelia Danuweli and Gini Reticker reflect on what this peaceful revolution meant.

Hosted by Mame Peya Diaw in Nairobi, Kenya. With original reporting and editing by Carielle Doe in Monrovia, Liberia. Marta Rodriguez Martinez, Naira Davlashyan, Lillo Montalto Monella in Lyon. Lory Martinez in Paris, France and Clizia Sala in London, UK. Production Design by Studio Ochenta. Theme by Gabriel Dalmasso. Our editor in chief is Yasir Khan.

About Cry Like a Boy Cry Like a Boy is an original Euronews series and podcast that explores how the pressure to be ‘a man’ can harm families and entire societies. Stay with us as we travel across the African continent to meet men who are defying centuries-old gender stereotypes and redefining their roles as men.

The podcast is available in French under the name “Dans la Tête des Hommes”. Listen to us on Castbox, Spotify, Apple, or wherever you listen to podcasts and don’t hesitate to rate us or to leave a comment. THE SOLDIERS OF LIBERIA: A MEN’S WAR – TRANSCRIPT

Mame Peya Diaw: Welcome to a new episode of Cry Like a Boy, a Euronews original podcast about how societal pressure on men to fulfill traditionally gender roles such as being the breadwinner, the head of the family, the glorious warrior or the hero can be harmful to a whole community. I am Mame Peya Diaw and I am with you from Nairobi, Kenya.

After listening to our last two documentary episodes set in the Liberian civil war about the role of traditional masculinity in armed conflict and soldiers suffering from PTSD, years after the battle is over, we are here with two very special guests, Oscar-nominated and Emmy Award-winning U.S. director Gini Reticker and Liberian Cecelia Danuweli of the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET) to discuss the role of women in conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

The Women in Peacebuilding Network was created in 2002 to unite Liberian women of different religions and backgrounds with a common goal: to stop the Liberian civil war that for more than a decade had threatened their lives and those of their families. All victims of violence and hunger.

Now If you haven’t heard the documentary episodes of our Liberian series, we invite you to do so by visiting our website. Hi Gini, hi Cecillia, thank you so much for joining us here on the Cry Like a Boy podcast. We will get back to you in a minute.

Gini Reticker, whose career is distinguished by placing women at the center of her stories, released the 2008 documentary Pray the Devil Back to Hell, which recounts the struggle of this group of Liberian women to demand an end to the armed struggle from the men.

In addition to listening to this conversation now, do you think women can be peace enablers? Can their voices be heard in men dominated societies? How do they fight to make a change? Let’s discover it now in this episode. Let’s start with you, Gini. How did you discover this story and why did you decide it was worth traveling to Liberia and making a documentary?

Gini Reticker: First, thanks so much for having us both here today. And it’s interesting, I actually heard about the story of women in Liberia by a very chance encounter with the producer, Abby Disney. She had just gotten back from Liberia in a celebration of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s inauguration as president and came back and we ran into each other and she was saying, while I was there, I heard something really interesting had happened in Liberia. And, you know, I was following the story in Liberia. I thought and all that I had heard about what was happening with women was just horrible stories of rape and violence. And I was like, I don’t know what you’re talking about. And there was no reporting of it at all in the mainstream media in the United States. And then Leymah Gbowee came to speak at the United Nations. And Abby and I went and met with women, got in a hotel lobby with her story, the story of all of the women in Liberia. And I was completely blown away and said, well, if this is really true, this is a film. And I think within a few weeks we were on a plane to Liberia.

Mame Peya Diaw: Thank you Gini for your answer. Back then, thousands of women, ordinary mothers, grandmothers, aunts and daughters, both Christian and Muslim, came together to pray for peace and then staged a silent protest outside the presidential palace, putting pressure on Liberian men to pursue peace or lose physical intimacy with their wives. Among them was Cecilia Danuweli. How did you become part of this movement and when did you decide that women had to intervene to stop the war?

Cecelia Danuweli: Well, I thank you for having me on this podcast. I decided to join this group in 2002 when the war began to rage in the capital, Monrovia, because I was a displaced woman coming from Boone County, from Bangor. And then when I came and saw how women were treated and others were treated, the men, the younger children, the way they were and we’re dying of hunger. And I was like, we need to stop this thing. We need to stop this war. And then I came in contact with Leymah (Gbowee) and she brought us onboard all 23 of us. We started the whole process where we had our first meeting and then she called me and I was among those 20 women that joined the whole process. And we started with the advocacy committee from the embassy to protest in the marketplace. We had what we call the Peace Corps project. And from there we started this mass action for peace under the banner of WIPNET (Women in Peacebuilding Network).

Mame Peya Diaw: I see and it’s interesting to see how you managed to succeed with this mass action because Liberia at that time had extremely limited civil rights, but still thousands of women from various classes mobilized their efforts and staged these nonviolent protests. So, Cecillia, how did you organise yourselves to bring so many different women together? What did you say to the men so that they would listen to you?

Cecelia Danuweli: We started atour homes, we started to feel almost like disciplining our husbands, that we were not going to have sex. We’re not going to do anything because we’re not happy. And because of that, they were like, ‘oh, I got to pay attention to you guys’. And so we started going from market places, from schools. We went to the schools we tried to bring on board after we started the whole process of explaining to the public, especially when they saw we started the market fully. We went to one of these schools and it was kind of my move. And at that time we saw the elderly. They were dying of hunger. We saw the women, some of them were being raped and were extremely distressed. And we saw the children, some of them, were dying. And I was like, what? This thing I feel we need to put an end to this. So it means that we all need to come together as women to go after this. And so we started going from the marketplace, we went to the schools, went to the mosques, we went to the churches, all up to making sure that we put an end to this carnage because we heard that we went to the concert and the rebels were supposed to go from street to street, from house to house. And we’re like, we can stay in your house and allow this to go on. So we need to have a safe space. And it was the fish market where we congregate every morning. If it rained, we repeated, sunshiny, we are there. And so we took it from all fronts, from our homes to the community, from the community. And then we went to the larger society where we communicate. And if you and thousands of people were going to their funeral homes or going to their houses, going to work. They will see us doing it. And so we started joining and joining the people who are just coming. We had the space and the place was so crowded. They started to join us. The Muslim women started to join when the Christian women started to join and all of that. And that’s how we mobilized the entire country because we came from different countries and cultures. If you come from your county, you make sure that your county gets involved with the entire country. So all of the counties were a part of this whole mess.

Mame Peya Diaw: And this must have been quite a challenge, considering that at that time, Liberian men would not see the damaging threat that their actions or behaviors would put on the whole community. I’ll come back to you later Cecilia. Gini, what was your first encounter with these women like? What struck you the most the first time you met them?

Gini Reticker: The first time I met these women, I think, was in December of 2005. So the war had been over for a couple of years. And Leymah brought about 20 women together for me to meet, for them to tell their stories. And I think it was probably one of the biggest impressions on me in my life because there were 20 women gathered at that point. There was still very little electricity in Liberia because it had been knocked out during the war and women sat around in a circle and told the stories of what they had been through. And, you know, it was a 14 year war. So people had very different stories over a long period of time, though, people basically everybody talked about some of the same things. But I remember just being completely blown away by the determination and strength of the women and by the commitment. And I remember asking. How did you keep going? How did you do this? How did you keep going and what would happen when you would get down? And somebody started to say we would sing and somebody started to sing, and then the women all started to hum and sing together and the sun was going down. We were losing light. We couldn’t keep filming. And I remember walking away feeling like. I was charged with the profound responsibility to try to get the story right.

Mame Peya Diaw: Absolutely because of their determination and strength like you just mentioned Cecilia, today these women are recognised for their braviour. And according to Leymah Gbowee, responsible for leading this nonviolent peace movement, women felt like Liberian men were really not taking a stand for them. They considered these men like fighters or they were very silent to them, accepting all of the violence that was being thrown at them as a nation. So here’s a question for the both of you. Why do you think it was the women of Liberia and not the men who organised to demand peace?

Cecelia Danuweli: Because the men, they could not come outside to do anything. If they came outside to say something or to do anything they were constricted. The young boys were constricted and taken to the front to fight. Whether you agree or not, the men were also taking the child soldiers with them. And we couldn’t just stay there and allow our sons and our husbands to go to the frontline. And so the women decided that they were the mothers to go. And in Liberia, if a woman decides to do something, especially coming up in that particular area or going to that party, perform that particular fact, they are effective because they know that if women are braver, we are committed to the process. And so we went, oh, we couldn’t allow our children because they would be killed. Our husband will be killed if they come up. That’s what I thought it meant for all our boys. We were out there doing all other things for them at that time so they couldn’t get outside.

Mame Peya Diaw: Same question for you, Gini, why do you think it was the women of Liberia and not the men who organised the demand for peace? Gini Reticker: I actually don’t think I have anything to add to this. I mean, I agree with what she said that the men would have been in danger. I remember Leymah telling me that, like, they didn’t invite the men to come on to the field with them where they were protesting every day, because if their men were there, the women would get attacked. They were much safer, braver it was. And they were from both religions, both factions. They were able to bring things together and to put a moral shame on people too.

Mame Peya: Thank you to the both of you, Gini and Cecelia, for your thoughts on this very important subject. Thank you for joining us here on Cry Like a Boy. Credits:

Mame Peya Diaw: Thank you for listening to Cry Like a Boy. In the next episode, we’ll continue our conversation and dive into the ways in which women can have an impact in conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

This show has been produced with me, Mame Peya Diaw from Nairobi, Carielle Doe in Monrovia, Liberia, Marta Rodríguez-Martinez, Naira Davlashyan and Lillo Montalto Monella in Lyon. Special thanks go to Lory Martinez, Clizia Sala and Studio Ochenta for helping us produce this podcast. Theme by Gabriel Dalmasso. Our editor in chief is Yasir Khan.

I would like to thank our guests Director Gini Reticker and Cecelia Danuweli. For more information on Cry Like a Boy, a Euronews original series and podcast, go to euronews.com to find opinion pieces, videos and articles on the topic.

Please do not hesitate to listen and subscribe to the podcast on euronews.com or Castbox, Spotify, Apple, Google, and Deezer, and, of course, give us a review, if you wish!