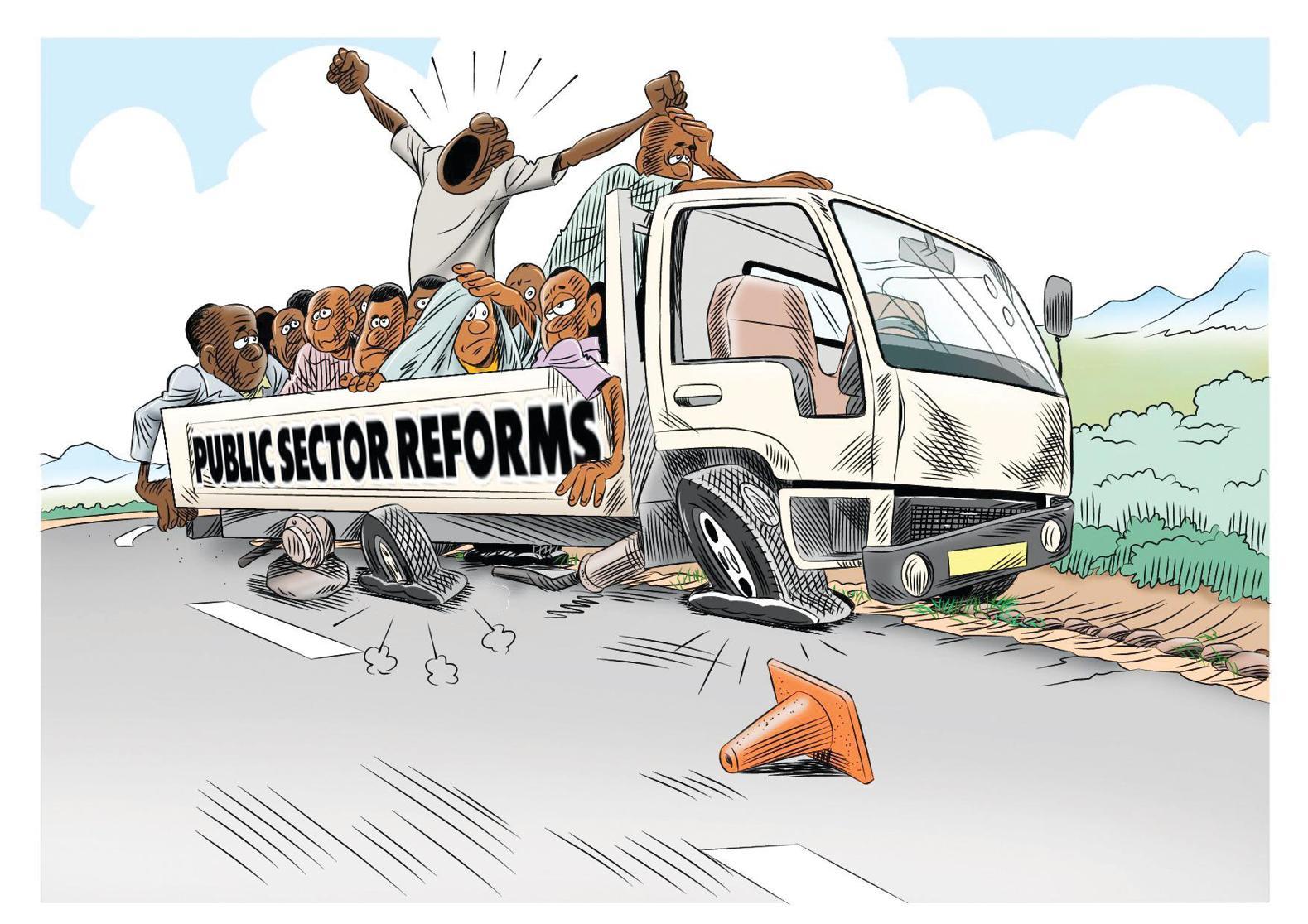

Africa-Press – Malawi. THRONG FOR A SERVICE—Passport seekers at Immigration Department in Lilongwe last yearThe authorities pitched them as a magic wand for improved government services delivery to the public but 10 years after the launch of the current lot of Public Service Reforms, Malawians are facing deterioration of public service delivery in many sectors.

From hospitals to schools to immigration to road traffic department, accessing a public service, let alone a quality one, is increasingly becoming a nightmare.

In some cases, and against the promise of the reforms, it is growing as a preserve of the few that have money to ‘tip’ their way through while the majority that cannot afford a bribe languish in long waits for a service that may never come.

For an illustration of the public fatigue with service delivery, over the past 10 years, Afrobarometer has conducted at least five surveys, a number of them delving into public service delivery in Malawi.

Our review of the surveys has found mounting public discontent.

For commentators, the failure of the reforms to deliver on public goods ought to have been expected.

According to them, Malawi’s reform drives largely have been an exercise in futility as they are more about political posturing for leaders to be seen to be doing something than real political desire at all levels of government to get things really done for the Malawian public.

Kondowe“We have failed to yield meaningful results because of a combination of weak political will, institutional inertia and no desire for accountability,” said Benedicto Kondowe, chairperson of the National Advocacy Platform, a coalition of civil society organisations.

Before 2015, Malawi had had a raft of public sector reform initiatives both locally and externally driven.

In February 2015, the Peter Mutharika administration launched a new wave of reforms as an impetus for the previous ones.

It described the effort as a “surgery” that would remove the abscess that had rendered public service delivery so sick in Malawi for too long.

It would start with institutional reforms, with the ultimate goal being for the public to be served better.

While the reforms may have produced positive results in terms of institutional arrangements in some sectors, today, 10 years on and two governments later, citizens complain of largely worsening conditions in critical sectors.

One example is in health.

A report of the Afrobarometer survey dated June 20, 2025, shows that most Malawians complained of struggling to access public health services.

According to the report, among the 73 percent of Malawians who said had visited a public health clinic or hospital during the previous year, more than six in 10 (62 percent) of them said it was “difficult” or “very difficult” to access the health services they needed.

The survey further found that in 10 respondents who reported having visited a public health facility, at least 8 of them (81 percent) encountered a lack of medicines or medical supplies and endured long wait on the queues.

Many others reported high costs that prevented them from getting needed care (69 percent), absent medical personnel (50 percent) and facilities in very poor condition (46 percent).

Kondowe said Malawi’s failure on the public service reforms is not surprising.

“Reforms have often been introduced as donor-driven tick-box exercises rather than homegrown, context-specific strategies grounded in national priorities and citizen needs,” he said.

He said that while leadership changes have frequently disrupted continuity of the efforts, entrenched interests resist transformation for the sake of preserving personal or political gains.

Poor coordination among government agencies, coupled with weak monitoring and evaluation frameworks, have also meant that implementation is sporadic and outcomes go largely unmeasured or ignored.

“Without a coherent vision, reforms become disjointed, underfunded and ultimately abandoned,” he said.

To fix this, he said, Malawi should adopt a results-oriented and citizen-centred approach to public sector reforms.

This should be anchored in national ownership, sustained leadership commitment and robust accountability mechanisms.

“This requires insulating reform programmes from political interference through the creation of an independent and empowered reform authority,” he said.

KambwandiraWilly Kambwandira, Executive Director for Centre for Social Accountability and Transparency, said there has been lack of transparency in the implementation of the public sector reforms because some government officials feel targeted.

“And the persistent corruption involving senior government officials has undermined reforms initiatives by diverting resources meant to implement the reforms, ultimately eroding public trust,” he said.

According to the Public Sector Reforms Management Department (PSRMD), lack of funding has been one of the major setbacks to the implementation of the reforms.

Other challenges include coordination gaps, technological limitations and persistent delays in procurement processes, it says.

“If reforms are to make significant impact on public service delivery, Treasury must financially support ministries to implement critical reforms and reduce the ministries’ dependence on donor resources,” said Suzgo Khunga, Director of Reforms (Information, Education and Communication) in the PSRMD.

Khunga said currently, Vice President Michael Usi is leading review meetings of reforms in councils and parastatals after which a full progress report of implementation for the last two years will be produced.

According to a PSRMD media brief dated June 2, 2025 on the progress of reforms in 20 ministries, inadequate financial resources for full-scale implementation of the reforms is a major challenge.

In the media brief comprising 20 ministries, lack of funding appears under 10 ministries, in addition to other challenges.

These ministries include Ministries of Basic and Secondary Education, Trade and Industry, Transport and Public Works, Tourism, Health, Youth And Sports, Labour, Information and Digitalisation, Lands, Water and Sanitation.

Between 1963 and 2014, Malawi implemented several reforms including the following: The Skinner Commission of Enquiry (1963), the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Public Service Review (1966), World Bank Malawi Public Sector Review (1991), the Chatsika Commission of Enquiry (1995) and several other initiatives between 1994 and 2014.

For More News And Analysis About Malawi Follow Africa-Press