By

Jutta Urpilainen

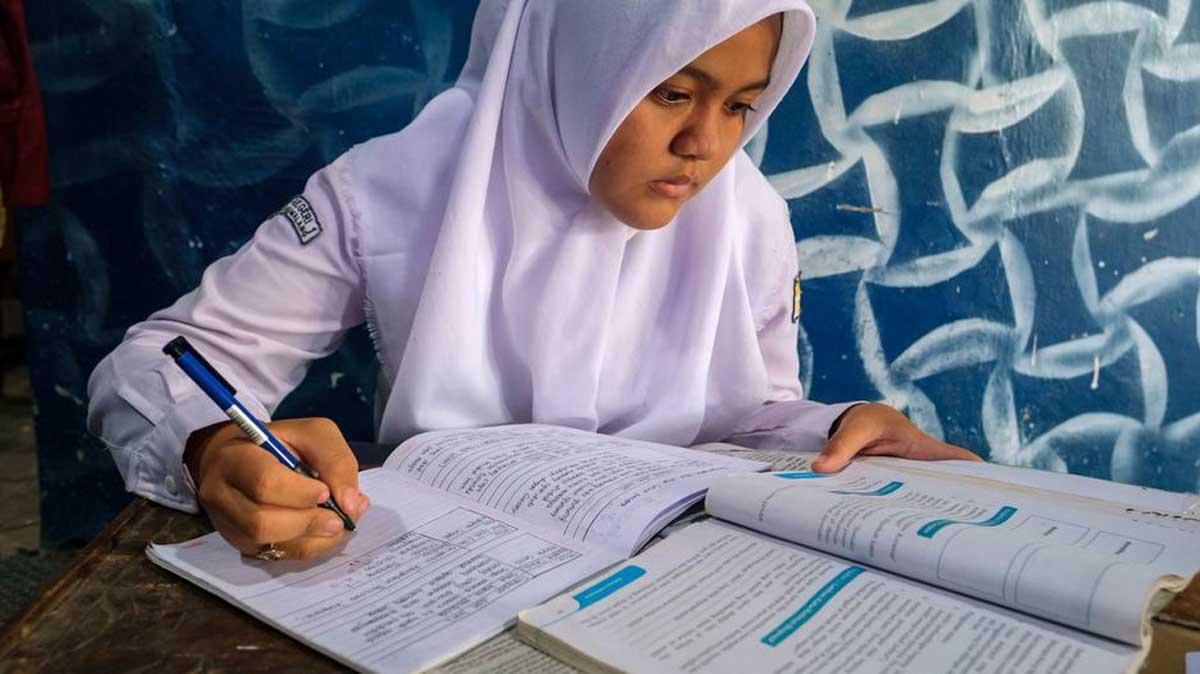

Africa-Press – Mauritius. As the former European Commissioner for International Partnerships, I have witnessed firsthand both the transformative power of education and the devastating consequences when it is denied. From the child in rural Papua New Guinea who walks hours to reach a school with no books, to the refugee girl in Jordan whose education was interrupted by conflict, and the young person in Uganda whose family cannot afford school fees, they all deserve better.

Yet our commitment to ensure quality education for all by 2030 is hanging by a thread. There are currently 272 million children, adolescents and youth out of school – 21 million more than we previously estimated, according to new figures from UNESCO. In low-income countries, only one in ten students achieve minimum proficiency in reading by the end of primary school. These children are not failing, I hasten to add. We are failing them.

There is no lack of commitment or understanding of education’s importance. What we have is a fundamental breakdown of our financing architecture. Countries have written national commitments to bring down the population of those out of school by 165 million by 2030, but low- and lower-middle-income countries face an annual financing gap of at least $97 billion to achieve their targets. In the poorest countries of this group, half of the cost to meet national education targets remains unmet.

In such contexts, external assistance represents a lifeline. In countries like Gambia and the Central African Republic, international aid accounts for up to half of all public education spending. Yet this critical support system is not only inadequate; it is actively deteriorating.

First, there is a stark mismatch between need and allocation. Only one-fifth of education aid reaches low-income countries, precisely where the financing gaps are most severe. Support for basic education, which covers the formative primary years, is waning and attention shifting to secondary or tertiary education. Meanwhile, we can see an 80% increase in scholarship spending since 2010. This is a worthy investment, but one that primarily benefits middle-class students who can navigate higher education systems, not the millions of children who cannot yet read.

Perhaps most alarming is what lies ahead. A new paper by the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report at UNESCO shows that, wrapped up in global politics, aid to education is projected to fall by a quarter between 2023 and 2027. These projected cuts could halve education spending in some low-income countries like Liberia and Chad.

The shift among donors from grants to loans compounds this crisis. Currently, 60% of education aid comes through grants – far more than for most other sectors – but the growing preference for loans threatens this balance. This trend risks adding to the debt burden many countries are already struggling with: 2.1 billion people live in countries that spend more on debt service than on education. How can we ask countries to invest in their children’s future if they are grappling with fiscal survival?

While donations are always welcome, the way they are disbursed is not always very effective. Bilateral aid increasingly bypasses national systems, leaning towards funding projects instead, which are easier to measure, monitor, and account for to taxpayers at home. Only 17% of funds from bilateral donors are channelled through recipient governments, compared to 60% from multilateral organizations. In the most extreme examples, such fragmented disbursement means that the number of donors per country is in the high twenties, leaving a huge administrative headache for ministries to manage.

As humanitarian crises multiply globally, donors are understandably redirecting resources to emergency response. Therein lies a misunderstanding, however. According to new research by the GEM Report and Education Cannot Wait, a growing share of development aid is being directed to education in emergencies and protracted crises. In 2021, nine out of every ten dollars being spent on education in emergencies came from development aid. In a time of reduced finances, clarity like this is critical.

The upcoming Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development taking place later this week offers a crucial opportunity to address some of these challenges, but only if we are willing to fundamentally rethink our approach.

Don’t think that we don’t have the resources. We do. Just two and a half days’ worth of annual military spending equals the amount going on aid to education per year. But we need political will. The international community must recognize that education financing is not charity, it is an investment in our shared future, and a more peaceful one at that.

The outcome document for this month’s conference that world leaders will be discussing includes a commitment to support adequate financing for inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all. This needs to be carefully monitored. Donor countries have not honoured their commitment to dedicate 0.7% of their gross national income to official development assistance but are also on course to reduce their contribution to levels not seen since 2000. It is never too late to learn from past mistakes, of course. All those working on education in country and at a global level must remind donors to respect the principles of the Paris Declaration on aid effectiveness, especially ownership and alignment.

The outcome document crucially also calls for reforming the international financial architecture and addressing the crushing cost of borrowing. Since 2015, the average share of education in total public expenditure has fallen by 0.7 percentage points, and in middle-income countries by as much as 2 percentage points, under the pressure of rising debt. Such reforms cannot come early enough.

We owe it to the world’s poorest countries to find ways to lower their lower borrowing burdens. Debt-for-education swaps have already been successfully implemented between Indonesia and Germany (2002-2011), Peru and Spain (2006-2017), and Côte d’Ivoire and France (2023). Such innovative methods must be expanded and explored.

The point to understand is that the cost of inaction extends far beyond individual tragedy. Countries with better-educated populations are more resilient, more innovative and more peaceful. They are better equipped to address climate change, reduce inequality, and build sustainable economies. Education is the foundation upon which all other progress depends. The question is not whether we can afford to properly fund education globally. It is whether we can afford not to.

moderndiplomacy

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press