Africa-Press – Mauritius. There is a close relationship between education and social evolution in any country. It is paradoxical to find out how the descendants of those Indian Indentured labourers who came to step in the shoes of the emancipated slaves in British plantation colonies succeeded in climbing up the social ladder within the lifetime of a few generations.

In so doing, they disrupted the former social order higher up the ladder and brought about a new realignment they had never thought of. How did this happen?

While the Second World War was still going on, a coalition of some of the major British political parties led respectively by Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain took over as a National Government.

It set up the Beveridge Commission to work out how to make Britain a safer place to live in once the war was over. Its report published in 1944 laid emphasis on education as the single major factor that could uplift the working-class people’s living standards and social status and avert social conflicts.

The logic was based on the principle that ‘an oasis of rich cannot live in peace surrounded by an ocean of poverty’. This reasoning led to the vulgarisation of education after the war with the creation of ‘Red Brick Universities’ over and above the elitist ‘Oxbridge Universities’ that produced talents for both domestic and colonial requirements, just like the Royal Colleges in the colonies.

What the British did was to open wide the doors of institutions to wards of working-class people who could not have attended school otherwise. University education was accessible to the working class through grants and scholarships.

Some 20 years later, a British Labour MP, commenting on the impact of education on social mobility, stated in the House of Commons: ‘Almost every senior civil servant has at least one working class parent.

’ Like the slaves, indentured labourers were brought to work in the plantations under a five-year contract.

As demand remained high, planters were forced to provide some incentives to attract more labour: free passage to spouse and children and payment of six-month advance salary while still in India.

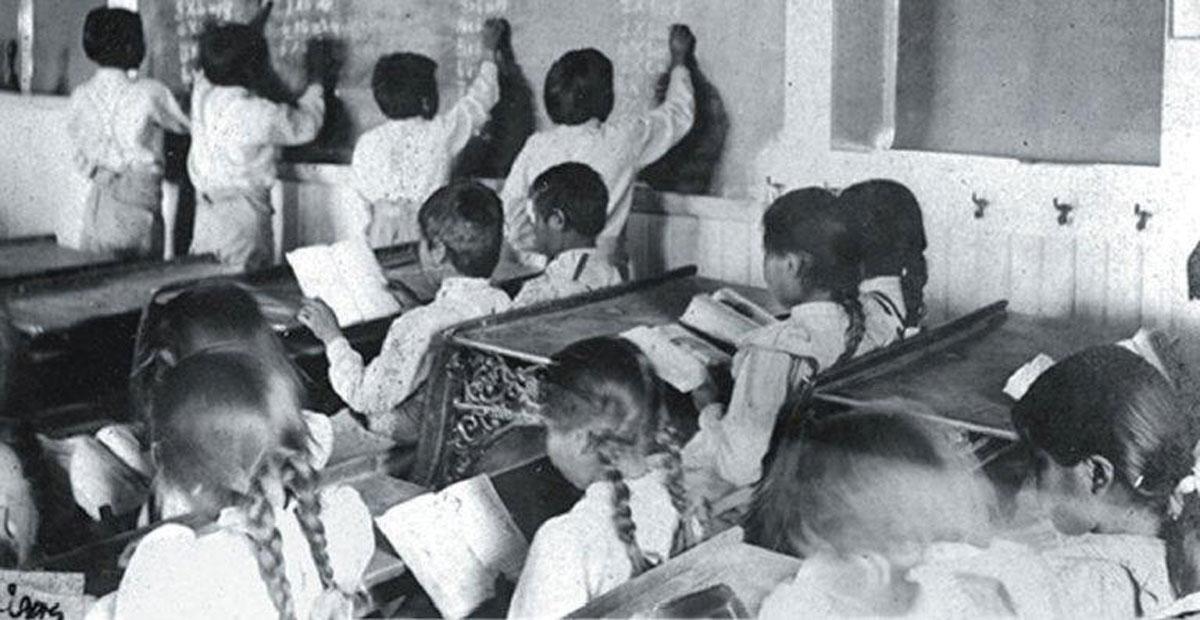

The colonial government provided free primary education, but not many could afford to attend those schools as they were far from plantation camps, and of those who did attend, the vast majority were urban males.

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press