Africa-Press – Mauritius. It is impossible to count the number of projects led by Chinese construction groups on the continent. From the Foundiougne toll bridge being completed in Senegal to the urban motorway under construction in Nairobi, not to mention the recent railway contract with Tanzania and Cairo’s Iconic Tower, Africa’s future tallest tower, Beijing has a huge appetite for African projects.

And – until now at least – it has had enough money to finance them. The wave of Chinese projects on the continent began more than 20 years ago after the Middle Kingdom launched its “Going Out” doctrine in 1999 and has only grown stronger over the years.

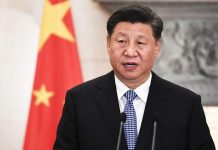

Today, it is on par with President Xi Jiping’s international ambitions and the weight of the companies he is dragging in his wake. …the relative share of Chinese groups remains virtually unchanged at 31.4% of projects on average, with a peak of 50% in East Africa and a figure of 30% in West Africa.

According to the latest ranking by US magazine ENR (see the top 10 below) – besides a handful of European businesses, including the familiar African companies Vinci, Eiffage and Bouygues – 14 of the world’s top 20 construction groups are Chinese.

Beijing’s leading position in construction, which has just been confirmed once again by Deloitte’s reference study “Africa Construction Trends”, is indisputable on the continent. The report, which covers the year 2020, lists a total of 385 projects worth more than $50m with a total value of $399bn.

As a result of Covid, these figures are down from 2019 (452 projects worth $497bn), but the relative share of Chinese groups remains virtually unchanged at 31.4% of projects on average, with a peak of 50% in East Africa and a figure of 30% in West Africa. Their ability to act quickly makes them unavoidable

“Chinese groups continue to benefit from their comparative advantages of competitive costs and their ability to act quickly, particularly on the financial side,” says Martyn Davies, Deloitte’s head of Emerging Markets & Africa, based in Johannesburg, South Africa. Ever since the health crisis began, Turkish companies have been less active on the continent. This is not the case with Chinese groups.

For example, according to their federation, French companies saw their relative market share on the continent drop from 24% to 8% between 2004 and 2017, while that of their Chinese counterparts jumped from 17% to 55%, in a market that increased sevenfold over the same period.

Since then, the French majors have passed the 10% mark again. Launched in 2013 by Jinping, the “One Belt One Road” initiative – with its African variation of mega-projects, particularly in the eastern part of the continent (such as in Djibouti, Kenya and Tanzania) – is obviously one of the reasons behind this rise in power.

But that is not the main point. “Out of all the sub-regions, there is hardly an infrastructure project, even a small one, that Chinese companies are not bidding on.

Ever since the health crisis began, Turkish companies have been less active on the continent. This is not the case with Chinese groups,” says a business lawyer specialising in infrastructure projects.

Uncommon expertise and financial power All of these projects not only have confusing acronyms – CCCC, CRCC, CRG, CCECC (see map below) – but also happen to be publicly owned groups.

Some are owned by provinces, but most, including the largest such as CSCEC, CCCC, Sinohydro and China Railway Group, are directly under the control of China’s State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (Sasac), a powerful state holding company.

Besides their size and expertise, acquired thanks to the formidable development of the Chinese domestic market, the secret behind the success of these companies in Africa lies above all in their financial power.

“The development model of Chinese groups in Africa in infrastructure and their growth over the past two decades is based on the provision of turnkey projects, but above all contracts that include negotiating financing from state to state,” says Richard Touroude, general delegate of the Syndicat des Entrepreneurs Français Internationaux (Sefi).

Levers named Exim Bank and CDB The levers of this strategy are the Exim Bank of China and the China Development Bank, which are under the direct supervision of Beijing’s State Council, and sometimes other players such as ICBC, the world’s largest bank, which is also public.

In addition, there is the export guarantee agency Sinosure. “In technical and quality terms, Chinese groups have undeniably progressed in recent years.

Competition with Western groups could therefore be fair at this level. But their opaque financing methods often give them a decisive advantage,” says Touroude.

The head of the French construction and public works company said that one of the reasons for this was because Eiffage beat Sinohydro to the €140m Singrobo dam in Côte d’Ivoire in a call for tenders led by the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC), which required transparency in the financial arrangements.

Lack of transparency To avoid distortions of competition linked to state support, Western companies are required to respect the framework of the Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits, adopted by OECD countries in 1978 and regularly revised, most recently in July 2021.

But China is obviously not a signatory to this agreement and no transparency rules appear in any other institutional framework (G20, WTO…). “It is almost impossible to obtain detailed information on Chinese financing agreements.

What we do know is that they generally include fairly harsh guarantee clauses, often based on assets,” says a business lawyer. In fact, although China provided nearly $12bn in financing and investment to Djibouti between 2012 and 2020, no one outside of those involved knows the actual financial terms.

Even within a consortium of Chinese and non-Chinese companies, the latter are not always aware of the financial terms of the contracts that the Chinese construction groups with which they are associated have entered into.

“The commercial and financial conditions linked to the construction of our railway between our bauxite deposit in Santou and the river port of Dapilong, carried out by China Railways Construction Group (CRCC), were negotiated only by the Chinese and Singaporean shareholders of our SMB-Winning consortium, we don’t know them,” says frenchman Frédérique Bouzigues, general manager of the Société Minière de Boké (SMB).

His company is the beneficiary of the rail, even though his teams only ensured the technical and quality monitoring of the site. An era about to end But the Chinese builders’ era of unrestrained expansion may be coming to an end.

Firstly, according to professionals, “Chinese-style” packages on projects – including the import of labour and materials – are tending to become rarer.

Two of the Chinese construction giants’ stated priorities are to employ a majority of African employees on construction sites and hire local subcontractors.

We feel that the desire for growth at all costs in Africa is waning. Even more crucial is the issue of financing. The Covid-19 health crisis has put a strain on the finances of many African countries, such as Chad and Congo-Brazzaville.

And Beijing has paid lip service to some of the discussions held within the “common framework”, which was developed this year to manage the losses caused by the pandemic (Debt Service Suspension Initiative).

But the majority of Sino-African bilateral debts are negotiated directly between Beijing and the continent’s capitals, often painfully. According to the John Hopkins University’s China Africa Research Initiative, Beijing has suspended $12.1bn in debts owed by African states since the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis.

And now, African leaders, such as the DRC’s Félix Tshisekedi, have started to publicly question infrastructure contracts signed with Beijing in the past. Changing trajectory

China’s state-owned export banks are also becoming more cautious, in line with the more selective growth policy of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 14th plan (2021-2025).

“We feel that the desire for growth at all costs in Africa is waning,” says one professional. According to Deloitte, the share of projects financed by China fell from 20.4% to 14.8% between 2019 and 2020.

Players such as Exim Bank of China and the guarantee agency Sinosure have reached their limit when it comes to the most indebted African countries and are reluctant to increase their risks further. In an analysis note dating from December 2020, the British law firm Pinsent Masons’ Beijing office confirmed this change in trajectory.

Some Chinese construction groups are now even seeking financing from outside China, from commercial banks or even development institutions based notably in Europe, where rates are lower than in China. At the same time, industry insiders have noted that other Chinese commercial banks less tied to Beijing’s foreign policy are becoming more involved.

“The rise in commodity prices on the continent continues to act as a powerful pull factor for many of them,” says Davies, who believes that Chinese construction giants have a bright future ahead of them. Even though they are no longer growing at the same rate, they have no plans to withdraw.

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press