Africa-Press – Mauritius. The 1st of February is a special day for all Mauritians because it reminds us of the long and valiant resistance of the Mauritian slaves against the system which denied them their humanity. Furthermore, during this period, the Mauritian Liberated Africans formed an important segment of the colony?s population and labour force.

Almost a generation before the abolition of British colonial slavery, the imperial government of Great Britain passed The Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1807, which outlawed the importation of slaves into its colonies.

In March 1808, an Order-in-Council was passed by King George III, with the approval of the British Parliament, which stipulated that Africans or negroes who were seized on slave ships by the British Navy would be forfeited to the British Crown.

The Africans, who were captured on these slave vessels by the naval forces of Great Britain, were also called ?Liberated Africans?, ?Prize Negroes?, ?Government Apprentices?, ?Government Blacks?, ?African Recaptives? and ?Prize Slaves?.

According to the royal Order-in-Council of March 1808, these Liberated Africans had to be apprenticed for 14 years, so that they might receive instructions from the masters or employers to whom they would be assigned.

The purpose of this order was to train the Liberated Africans or Prize Negroes in a specific job, so that they would be able to support themselves in the future and eventually become free and productive members of colonial society.

However, in the long run, during the course of the early nineteenth century, this supposedly benevolent scheme of the British imperial government, which was based on so-called British liberalism and humanitarian ideals, proved to be an abject failure.

In Mauritius, local colonial officials held the view that the Liberated Africans should not be freed immediately upon their arrival in the colony and, at the same time, that they could not be returned to their land of origin.

The main reason being that the British government of Mauritius, like many other colonial governments of the period, firmly believed that the Prize Negroes could be re-enslaved in their native lands.

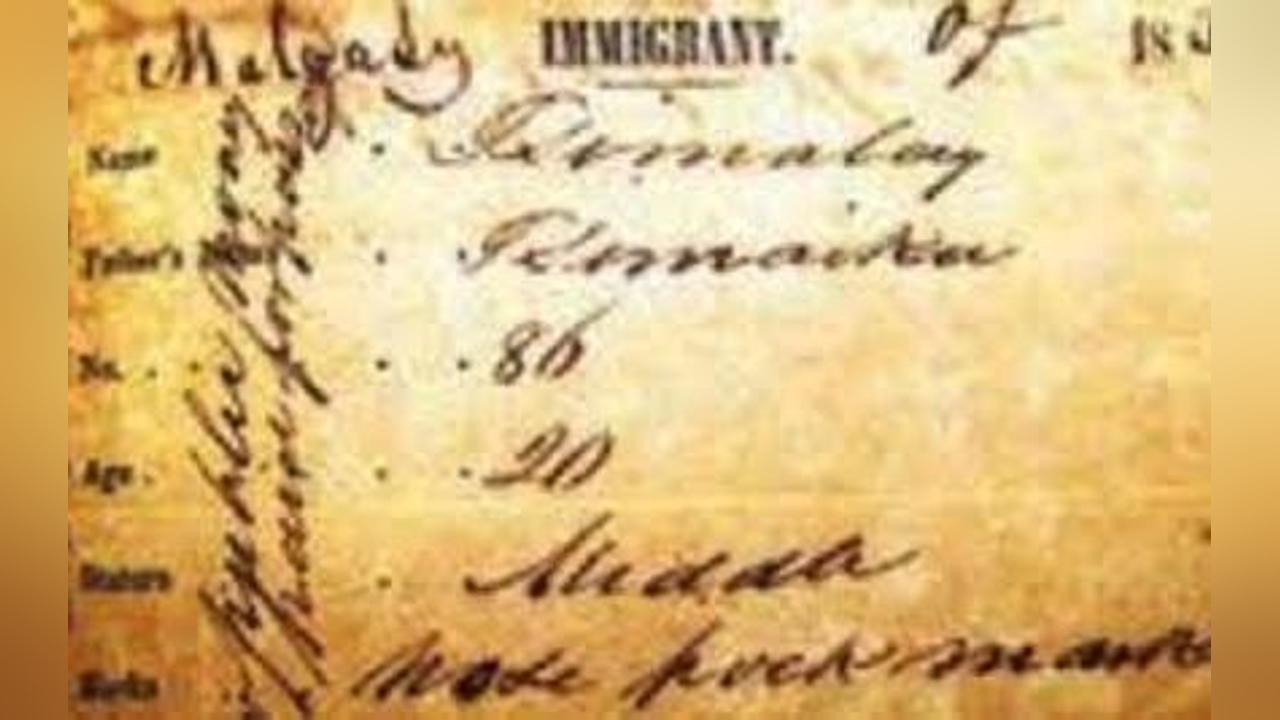

The allocation system In general, what happened to the Liberated Africans or Prize Negroes when they were landed on Mauritian shores? In 1830, Richard Vicars, a British citizen who resided in Mauritius for several years, wrote in his pamphlet entitled Representation of the State of Government Slaves and Apprentices in Mauritius: ?The Apprentices are those Negroes who have been rescued from slave-ships since the abolition of the Slave Trade, and are bound by the Collector of Customs for the period of fourteen, and latterly for seven years to private individuals, who, by the indentures they sign, engage to teach them a trade or occupation by which they may earn a livelihood?? When Liberated Africans or Prize Negroes arrived in Mauritius, they were taken to the Customs House in Port Louis harbour where they were turned over to the Collector of Customs.

He was the British officer who was responsible for all the Liberated Africans in the colony. In February 1839, George C. Cunningham, the Collector of Customs, sent an important despatch to George F.

Dick, the Colonial Secretary of the local British government, in which he explained that ever since 1811, government apprentices in Mauritius fell into three specific categories.

In the first category, the majority of the government apprentices were allocated to private employers who were given the responsibility of teaching them a particular trade.

In the second one, a smaller number of apprentices were employed as labourers, messengers, and artisans in the various departments of the local British government, mostly in Port Louis.

The third and last category of apprentices was enlisted into the colony?s land and sea forces. Immediately after arriving in Port Louis, all Prize Negroes were ?condemned? by the Vice-Admiralty Court of Mauritius.

Between 1813 and 1827, almost 3,000 Liberated Africans were landed in Mauritius and over 2,400 apprentices were allocated to more than 660 private employers or masters, with the majority of them obtaining fewer than 9 apprentices.

During the 1810s and 1820s, 224 Liberated Africans were enlisted into the British military and naval forces which were based in Mauritius. Furthermore, between 1813 and 1827, around 206 apprentices were employed as labourers, artisans, and messengers in the various departments of the local British colonial government.

The indenture agreements Once the Liberated Africans began to serve their 14-year indenture, they became known as government apprentices. The Collector of Customs played a pivotal role in this entire process, especially when the apprentice was going to be assigned to a private employer or master.

Moses F. Nwulia, an American slave historian, explains that before a private employer was given an apprentice: ?He was required to enter into contractual obligations, a process known as «articling», with the collector of customs, who acted on behalf of the government?.

According to an indenture agreement from the mid-1810s, the employer or the master was obliged to provide his apprentice with an adequate amount of food, clothing, shelter, and medical care. The employer was given the responsibility of instructing the apprentice a particular trade or ?other useful employments?.

Between 1826 and 1827, the Commissioners of Eastern Enquiry, while investigating the illicit slave trade and the condition of Mauritian slaves, took a special interest in the terrible plight of the Mauritian Liberated Africans.

In June 1829, in their report on the illegal slave trade to Mauritius, Commissioners Colebrooke and Blair concluded that the Prize Negroes were treated no better than the Mauritian slaves and, in some cases, they were even worse off than most of the colony?s slave population.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the Royal Commissioners even advanced the idea ?that the majority of the negroes who are captured in slave ships would be desirous of returning to their country is probable.

? Departed Liberated Africans In March 1827, The Return of Prize Negroes condemned at Mauritius between 1813 and 1827 clearly showed that 5 Prize Negroes were restored as «free and allowed to return to their countries» of origin.

Thus, by 1827, out of a total of almost 3,000 Liberated Africans who were landed and out of more than 2400 Prize Negroes who had been apprenticed to private individuals, only 5 Liberated Africans were given permission to return to the countries of their birth such as Madagascar and Mozambique.

Another way which government apprentices left the colony was when they went abroad with their masters or mistresses. According to one of the conditions in the indenture agreement of a government apprentice, the employer had to obtain the written permission of the Collector of Customs before he or she could legally take an apprentice out of Mauritius.

This written permission was a «permit of embarkation» and in general, it was easily obtained. Between 1816 and 1825, roughly 45 Liberated Africans left Mauritius with their employers and traveled to such places as England, India, New South Wales, the Cape Colony, and Ceylon.

In all, 39 males and 6 females left the island which clearly shows that the overwhelming majority of those who left were males. Furthermore, around 25 Prize Negroes went to England, 13 to India, 2 to New South Wales, 4 to the Cape Colony, and 1 to Ceylon. During this entire period, it is evident that England was the most common destination for the Liberated Africans who left Mauritius.

This fact is not surprising because the majority of the employers who took their apprentice with them overseas were British colonial officials as well as military and naval officers who were returning to Great Britain after several years of service in Mauritius.

It is also important to mention that four among the thirteen Prize Negroes who went with their masters and mistresses to India were the government apprentices of Captain Vine.

In August 1822, the ship in which they were traveling was shipwrecked off the coast of India and Vine?s apprentices managed to steal a boat and successfully made their escape by heading toward the coast of the Indian subcontinent.

There are several interesting examples of government apprentices who left the colony such as in 1817, when Ovah, a male Malagasy apprentice, who was employed by Colonel G.

A. Barry, Chief Secretary to Government, traveled with his master to England. Around the same time, Rahanafa, a male Malagasy apprentice, who was employed to Sir Robert Farquhar as a house servant, accompanied his master to England.

It is interesting to note that earlier that same year, Governor Farquhar sent a Malagasy apprentice to Madagascar with Sergeant James Hastie, the British Agent to King Radama?s court.

The task of this apprentice was to teach the Hovah, living near Tananarive, the use of the plough and to improve their agricultural methods. In 1820, Maria, a female Mozambican apprentice, who was assigned to Mr.

S. Peake, a British resident, left the colony with her master for Madras. In 1823, Makua, a male Mozambican apprentice, accompanied his employer Lieutenant Barnes to England on board the H.

M. S Menai, a famous slave-catching British naval cruiser. In July 1836, Mr. Cunningham, the Collector of Customs reported that by 1833, around 79 Liberated Africans had left the colony with their masters. Thus, between 1827 and 1833, or over a period of six years, 33 Prize Negroes departed from Mauritius for overseas destinations, usually England.

Each year, as the Mauritian nation honours the struggle for freedom, the achievements, and the legacy of the Mauritian slaves on 1st February, a special tribute must also be paid to the memory of the Mauritian Liberated Africans.

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press