Africa-Press – Mauritius. It would be trite to note that many countries which stand out as models to emulate today have laws aimed at fighting corruption, but very few governments as Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore turned the fight against corruption into a moral imperative, an unerring compass, a powerful political plank and a quasi-spiritual necessity, somewhat akin to a battle between good and evil or light versus darkness.

The country he inherited in 1959 was a malaria-infested backwater, with corruption rife under the rotting British colonial administration, the police, the judiciary, the institutions and, of course, the administration and civil servants governing a ubiquitous graft for permits and licenses state.

Singapore was further under threat, as Lee perceived it, from neighbours where corruption was endemic and an accepted way of life, considered either as a necessity to grease processes or as a low risk, high reward activity.

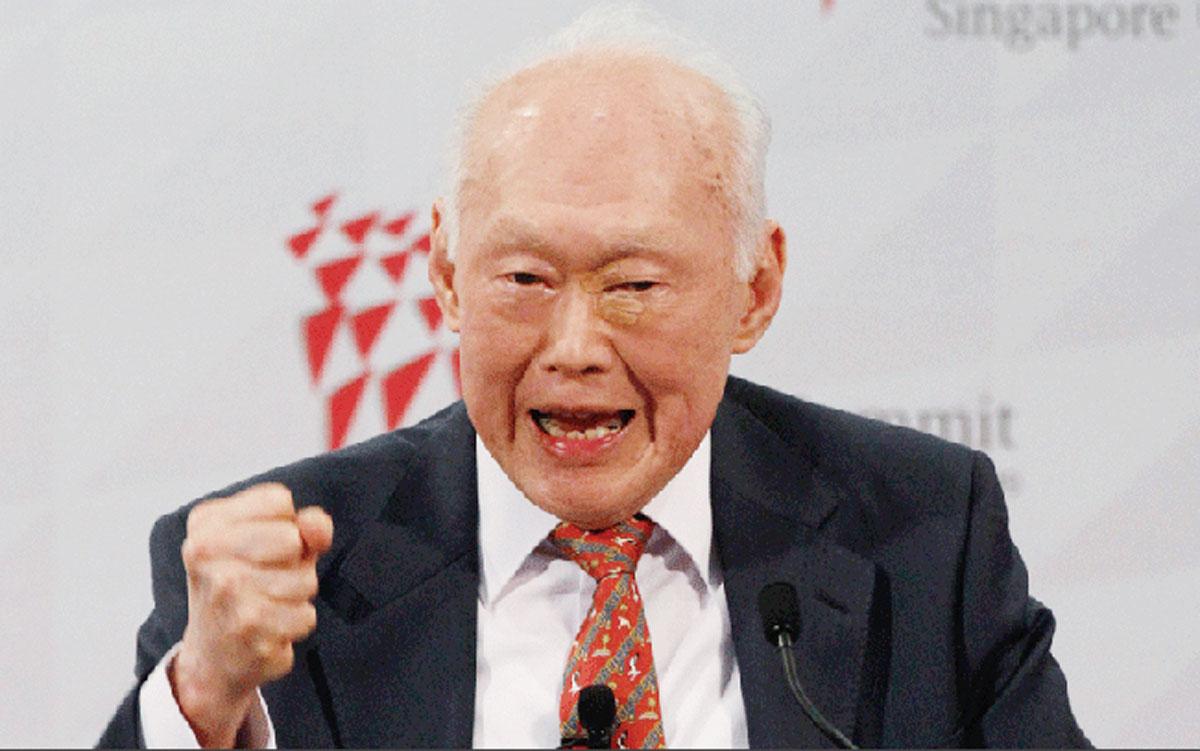

Corruption Fight and the Lee Kuan Yew Example.

Pic – African Examiner His unrelenting goal, even in that complex multi-cultural society, where race, religion and community fashioned voters’ minds, was to buck the trend and turn corruption into a high-risk, low-reward activity transcending those ethnic barriers.

Along that road, he was probably the butt of anger from hangers-on to the lucrative status quo and must have been the most criticised politician in Singapore.

But eventually he was proven right and soon enough Singaporeans of all confessions discovered and liked the idea of not having to wait, provide “gifts” or pay bakshish for timely delivery of quality services, businesses no longer needed to grease politicians for their investments or permits and Lee’s crusade, both moral and political, paid off handsomely.

The country has been for decades attracting banks, computer software, financial services, information services, manufacturing, in preference to so many neighbours and countries better endowed with natural resources, manpower, and markets.

In 2013, two years before his death, Lee Kuan Yew observed that his greatest satisfaction in life was that he had spent years “gathering support, mustering the will to make this place meritocratic, corruption-free and equal for all races – and that it will endure beyond me, as it has”.

It would be fair to say that few countries or world leaders would ever dare compare themselves to a man and leader of such exceptional character and wisdom and such a passionate love for his country. But as one US author wrote, “When Lee Kuan Yew speaks, presidents, prime ministers, diplomats, and CEOs listen. ”

Each and every country of course has to deal with its own context, history and economic development trajectory as it grapples with the powerful and the occult, the financial clout of local and established businesses or the lure of the wealthy or corrupt wannabee investor.

In an environment where low risk can be guaranteed by executive fiat over watchdog institutions combined with the willing servility of either their CEOs or their Boards, packed with protégés and top-notch civil servants who fail to act as expected bulwarks, the temptation for accepting or seeking the high rewards of corruption can manifestly drive any country to the dogs.

Since the MSM-ML dispensation took office end 2014, its most catchy promises (Metro Out, Water 24/7, meritocratic appointments,. . . ) fell by the wayside while notorious affairs (BAI/Bramer bank, Betamax, etc) for which we are still paying the costs, hogged the limelight.

Since then, a seemingly endless succession of scandals have kept the media busy on all fronts (Alvaro-gate, the virtual bankruptcy at Air Mauritius and firesale of its assets, the financial losses at SBM, the gross corruption affairs during the Covid pandemic, the assassination of the MSM agent Kistnen, the strange Wakashio disaster, the opacity of BoM/MIC lending to some crony businesses amongst many others).

Not all these affairs reek of corruption or graft, some we may assume are simple results of gross incompetence of political nominees, cronies and agents, others to a rising generation of civil servants less imbued with the sense of propriety of their predecessors, while others could not simply be bothered to stand up as whistle blowers and risk their career.

But the overall impression is that either the deadly combination of cronyism, nepotism and incompetence has attained unsurpassed limits or that pervasive corruption is now far too ingrained at all levels under the ruling regime for it to root it out even if it had the will to do so.

The latest tidings from the State House and the Mercy Commission (read elsewhere in MT) leave little room to doubt that 2023 in that regard may be no different to what we have witnessed so far with public interest and transparency taking a back seat.

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press