Africa-Press – Mauritius. Calls by African ambassadors at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva last week for a top–level investigation into racism and police brutality in the United States – as corporate apologias for links to the Transatlantic slave trade and demands for reparations multiply – show how the horrific police murder of George Floyd has resounded across the world.

It also shows the gulf between Western governments and their citizens. A poll by the Civiqs research agency in the US reports that the “Black Lives Matter” movement has support from 53% of US citizens, that’s a 10-point plus lead over President Donald Trump or his rival Joe Biden.

Nor should there be complacency in Europe. The polite insistence of officials in London and Paris that the blight of slavery and race laws in the US is somehow distant from European realities is a contrived misreading of history.

The campaign against racism and for reparations turned global in the month since George Floyd’s murder. Africans and Caribbeans joined the African-American cause, as did the youths of the multi-cultural cities in the West.

To their voice has been added Aboriginal rights activists in Australia, Dalits in India, Palestinians and Afro-Brazilians; and oppressed minorities everywhere.

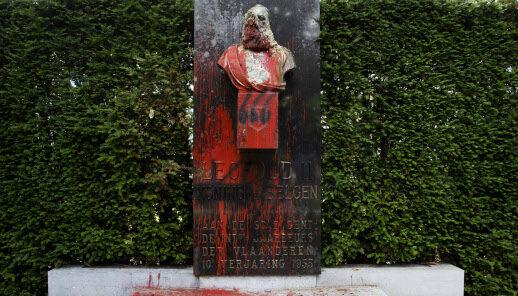

Activists are focusing on the next move. Those demanding the removal of statues of Confederate general Robert E Lee and arch-colonialist Cecil Rhodes have notched up key victories.

British companies such as the Lloyds of London insurers’ cartel and Greene-King breweries have belatedly acknowledged their predecessors’ profits from slavery.

How much of this is translated into policy reform and how much remains as corporate public relations depends on the political power driving the campaign. In most of Europe, mainstream politicians are reluctant to accord the same respect to those exploited in colonialism.

African Ambassadors in Geneva made a strong start with their call for an urgent debate on racism at the UN Human Right Council on 17 June and an independent Commission of Inquiry into the US criminal justice system.

After the resolution was backed by Africans, Asians, Latin Americans and a few Europeans on the council, the US State Department lobbied for a dilution of the text. Under Trump’s Presidency, the US quit the Council in 2018, accusing it of political bias. Washington managed to derail the investigative commission.

Instead, the UN’s Human Rights Commissioner Michel Bachelet, former President of Chile, is to prepare, with help from UN experts, a “report on systemic racism” and violations of rights by law enforcement agencies, “especially those incidents that resulted in the death of George Floyd …and other people of African descent.

”

Earlier that week, after national demonstrations against police brutality in France, President Emmanuel Macron said on television his government would stand strong against racism and anti-semitism but added: “the republic will not erase any trace or any name from its history … it will not take down any statue.

” The French cannot deny who they are, he said. Instead Macron wants to build a memorial to the victims of the slave trade in the Jardin de Tuileries, next to the Louvre museum.

The anger at demonstrations in Paris and a host of smaller towns, suggests this would be far too little, far too late. A few weeks before his election in 2017, Macron condemned brutalities inflicted on Algerians, calling French colonial rule of the country a “crime against humanity”.

Visiting Algeria the following year, Macron apologized specifically to the family of an activist tortured by French soldiers but stopped short of a general apology to the country.

Under his government there seems little prospect of even a statement of remorse for France’s role in the slave trade, still less for moral or material reparations.

Similarly, Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson argued that removing statues of slave traders, colonialists and white supremacists would be to “lie about our history and impoverish the education of generations to come”.

That is a bizarre assertion from a politician, styling himself as an historian, peppering speeches with references to Greek and Roman oratory. In truth, it is the narrow gauge of so much history taught in British schools that has proved impoverishing, bolstering a grandiloquent national self-image, and deepening social division.

For all their differences in style, Macron and Johnson share a reluctance to address honestly the roots of racism in Europe, the slave trade and colonialism. But that is what is required if this moment, the possibility for radical change, is not to be lost.

Europe’s former colonial powers – Britain, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Holland, Italy, Portugal and Spain –should set up Truth & Reconciliation Commissions to interrogate the legacy of empire and the slave trade.

Like the model pioneered in South Africa, the commissions should be independent of government and political parties, charged with the task of investigating and reporting on the brutalization and commercial structures of the Transatlantic slave trade and the colonial empires built around it.

They should hear testimony in public from those whose families suffered irreparable loss and those accused of benefiting from this epoch in which industrial Europe was built.

That would enrich education, restoring a social role for history: addressing trauma by collective healing. In Germany, in Ireland and in Canada, such commissions have had some success.

Alone among countries succumbing to fascism in Europe, Germany confronted its history, acknowledging the crimes of Nazism, building memorials to those murdered in the Holocaust.

Its progressive politicians have shown the humility to pay tribute, to kneel before monuments dedicated to the victims of fascism. In most of Europe, mainstream politicians are reluctant to accord the same respect to those exploited in colonialism.

That recognition would be a vital achievement of these Truth & Reconciliation Commissions, along with the resilience and confidence that comes when societies are able to appraise their past without delusion.

There would also have to be a reckoning, both moral and material, out of this history. Already this is happening, episodically with British banks and US insurance companies acknowledging the bloody roots of their fortunes.

And like bad Catholics in the Middle Ages, they are buying indulgences for past sins by financing public goods. Institutions such as University College in London have traced the slave trade origins of many British family fortunes. The last month of anti-racist activism has prompted more mea-culpas and offers of indulgences from plutocrats.

Yet this era of the pandemic – a hinge in history – offers a chance for a comprehensive rethink as societies try to balance shrinking economies with growing demands to cut inequalities and end the galloping destruction of the environment.

Africa, through floods, drought and desertification, has borne the brunt of environmental destruction so far. Its searing inequalities, lack of access to public health and education, have been underscored in the pandemic.

What needs to be done by all sides is set out clearly in the UN Sustainable Development Goals. It would be a form of respect and atonement for those countries which have benefited from a predatory past to contribute seriously to ensuring that the majority of humanity can achieve those goals.

It would require honesty about the past and future; a determined effort to end the scandal of $100bn in illicit financial flows leaving Africa each year for ex-colonial tax havens. It would also mean massive investments in green energy to power a continent that will have the biggest labour force in the world by mid-century.

Bottom line: At a time of geo-political turmoil, truth and reconciliation commissions offer a chance for European countries to face up to their histories and their futures as multi-ethnic societies.

And if pursued honestly, it would enable them to open a new chapter in relations with their nearest neighbours in Africa. If they don’t, expect turbulence.

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press