Africa-Press – Mauritius. Growing tensions behind the scenes will hit the spotlight on Wednesday and Thursday when the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) convenes the annual African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) ministerial.

With the unilateral trade preferences program up for renewal in 2025, Washington’s stated desire to negotiate two-way trade deals, which also benefit US exports, has been raising alarm bells in boardrooms and government offices across Africa.

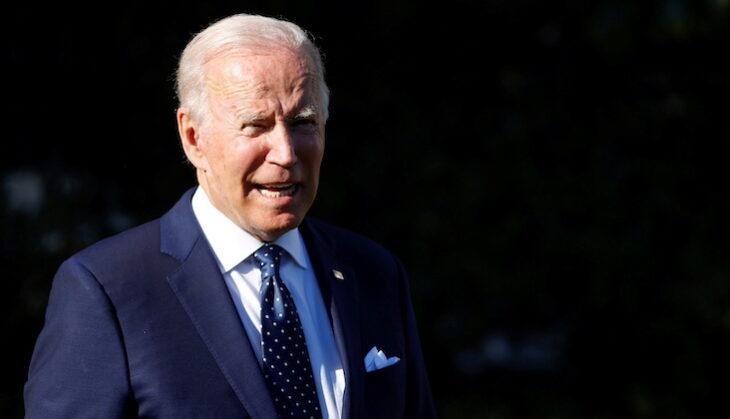

African exporters have already launched a lobbying campaign for AGOA’s renewal – even though the program doesn’t expire for another four years. Meanwhile, government officials have made it clear that they will use this week’s forum to press for more clarity from the Biden administration on what form US-Africa trade will take.

“The future is currently quite unclear,” Betty Maina, Kenya’s cabinet secretary for industrialisation, trade and enterprise development, told a private sector virtual forum hosted by the Washington-based Corporate Council on Africa on Tuesday “It’s a message that we’re going to be repeating today and over the next two days, that it’s really critical for the US to indicate and make clear what sort of regime it hopes to open up for Africa if AGOA is not extended.

” US buyers want stability and predictability. If they’re worried that they’re going to lose duty free because AGOA’s going to expire, they’ll start moving their business elsewhere…”

At the same event, Alan Ganoo, the Mauritian minister for foreign affairs, regional integration and international trade, insisted that “both sides need to work together on a mutually acceptable solution before AGOA expires.

“There is unanimity that the AGOA program has been beneficial to eligible countries [by providing] a powerful tool to increase exports, create jobs and promote economic welfare,” he said.

“Any post-AGOA 2025 strategy should not lead to the destruction of trade in any AGOA-eligible country.

” From duty-free to FTAs Then-President Bill Clinton signed AGOA into law in May 2000, ushering in a new post-Cold War Africa economic policy of ‘trade not aid’.

The program grants duty-free access to the US market for 1,800 products, in addition to the more than 5,000 products eligible under the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) program.

Last year, African duty-free exports to the US under the program amounted to $2.7bn, out of a total of $46.6bn in two-way trade in goods and services.

A total of 39 countries were eligible in 2021 based on their respect for market-based economy principles, rule of law and other criteria (Ethiopia’s eligibility is currently under review because of alleged human rights violations in Tigray).

While AGOA has been credited with helping lift thousands of people out of poverty, Africa’s greater economic growth over the past two decades has sparked calls to make US trade policy with the continent a two-way street.

As far back as the tail end of the Barack Obama administration in September 2016, USTR published a report titled ‘Beyond AGOA’, which examined the “need to develop new trade policies for the new Africa, given the broad spectrum of countries that now make it up and the changing global trading system of which it is part.

Under President Donald Trump, the US began negotiating a free trade agreement (FTA) with Kenya last year, which is seen as a possible blueprint for other sub-Saharan trade deals that could eventually replace AGOA. Likewise, the Biden administration has indicated that it’s thinking of moving beyond AGOA.

“In thinking about post-2025, we should assess how the broadest scope of partners can derive benefits from the US-Africa trade relationship,” Bennett Harman, the deputy assistant US trade representative for Africa told the 2021 US-Ghana Business Forum last month.

“As we’ve come to learn, attracting investment in emerging markets requires far more than just trade preferences, and so we need to be creative and strategic about how we chart our path forward.

I don’t think we want to be in a situation where we throw the baby out with the bath water when it comes to the fact that there are some 40 countries that benefit from AGOA….

” US business interests similarly support a new approach.

With China and Europe actively courting African markets, the US risks getting locked out of lucrative export markets, says Scott Eisner, president of the US-Africa Business Center at the US Chamber of Commerce.

“I don’t think we want to be in a situation where we throw the baby out with the bath water when it comes to the fact that there are some 40 countries that benefit from AGOA,” Eisner says.

“But … after 25 years of any unilateral trade preference program, there has to be a re-evaluation of, is this right for all the markets?”

African nations would also benefit, Eisner says, through increased predictability that’s highly attractive to potential investors. “AGOA always has the chance of being pulled out,” he says.

”There’s an annual review process, which means some countries can lose eligibility, and that uncertainty doesn’t necessarily exist in an FTA.

” Time is running out Ironically, loss of predictability is exactly what has AGOA advocates worried.

With Kenyan FTA talks having made little progress since Trump first endorsed the idea in February 2020, African exporters are worried that they could be left with nothing if AGOA renewal talks don’t kick off soon.

Every time the act has been up for renewal, or a major provision was set to expire, trade dropped off two years ahead of time, says Paul Ryberg, the president of the African Coalition for Trade, a Washington-based group that lobbied on AGOA issues on behalf of African business associations.

“Those who see no sense of urgency don’t pay attention to the trade numbers,” Ryberg says.

“They’re just looking at the policy, and not what it actually accomplishes.

“US buyers want stability and predictability,” says Ryberg.

“If they’re worried that they’re going to lose duty free because AGOA’s going to expire, they’ll start moving their business elsewhere, so we don’t have four years, we have two years, and two years is very short in the legislative cycle.

”

“[African nations] are by and large happy to negotiate FTAs, but we need to get off our duff and start doing it,” he says.

“…or we’re going to come up to 2024 with no FTAs and uncertainty over AGOA and the investment will disappear.

”

To help get that message out, the Lesotho Textile Exporters Association hired his single-member Washington law firm, Ryberg and Smith, last month for $10,000.

The firm was to help organise AGOA-focused meetings with US officials for Foreign Minister Matsepo Ramakoae during her recent visit to the US for the UN General Assembly.

“What we would like to see from the Biden administration, even if you are not talking details at this point, is at least a clear policy statement that reflects that […] they are committed to have a meaningful arrangement with Africa going forward,” says Nkopane Monyane, Lesotho’s envoy to the UN and a former African Group representative to the World Trade Organisation who works on the US trade file.

Monyane says the US should recognise “that FTAs will not happen quickly, and they will not happen quickly for all. ” Instead of a “think tank kind of approach” favoring the next exciting thing after AGOA, he urges policymakers to carefully consider the realities on the ground.

“For us this is about life and death,” Monyane says.

“Life of people in Lesotho who rely on AGOA, who rely on the garment industry.”

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press