Africa-Press – Mozambique. The growing threat of AI to destabilise democracies and consolidate autocracies needs to be proactively addressed. Ademola Oshodi argues that as Africa’s largest democracy and a cultural and digital powerhouse, Nigeria is ideally suited to lead the charge.

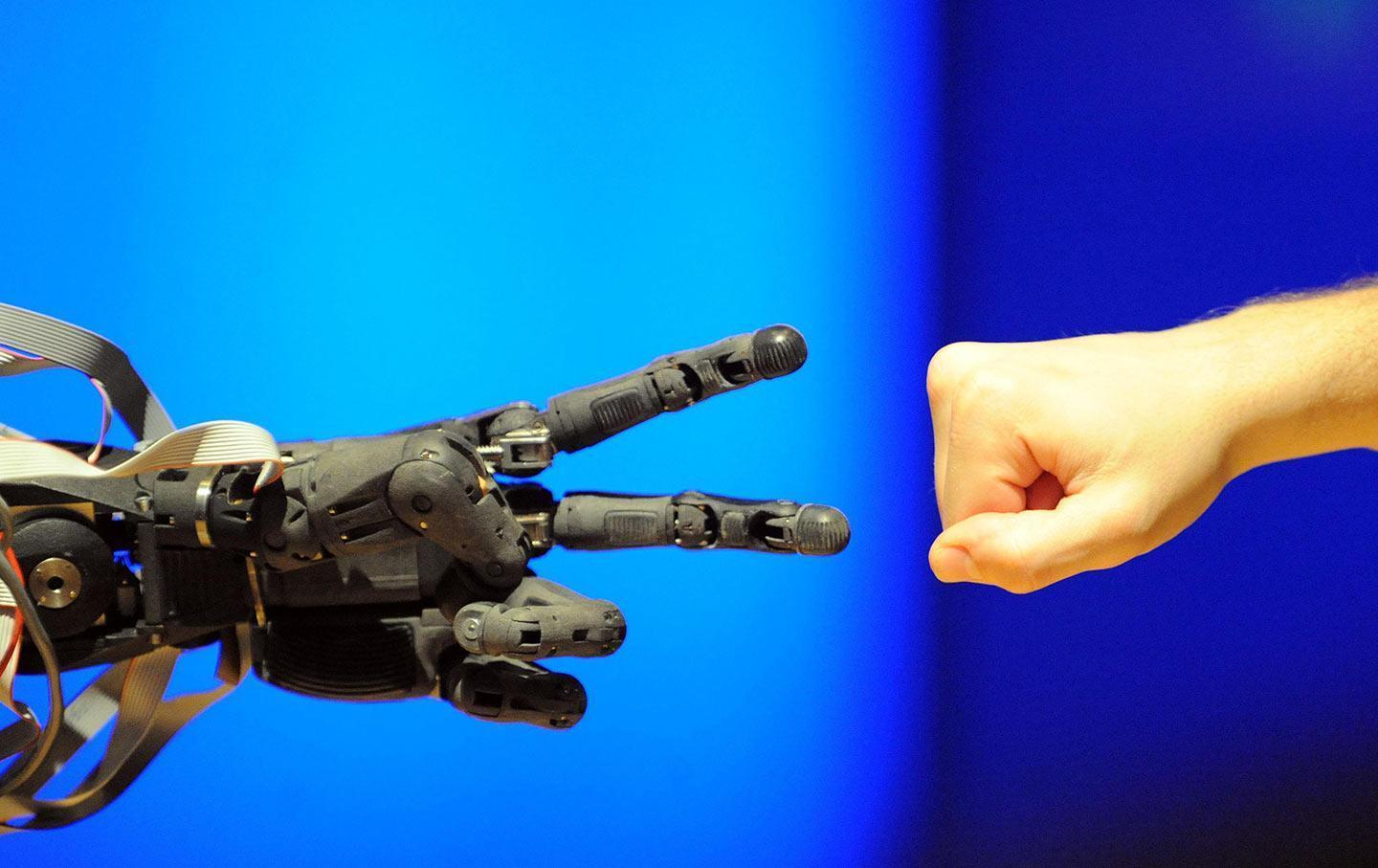

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a future disruptor; it is a present threat to democracies, which face the dual pressures of internal erosion and external manipulation. Around the world, AI is already being used to weaken democracies, manipulate public opinion, prop up authoritarian regimes, and dampen diplomatic credibility.

The risks are not confined to national borders. A recent DW report warned that AI-driven disinformation could destabilise elections across Africa in the coming years. With 18 African countries scheduled to hold elections between 2025 and 2026, the stakes are high. Africa is one of the key battlegrounds where the integrity of democracy will be tested by the malevolent use of AI. For Nigeria, Africa’s most populous democracy, the question is not whether AI will shape our political and social life, but how we choose to govern AI in ways that strengthen our democracy rather than undermine it.

In Nigeria’s 2023 elections, deepfakes and coordinated disinformation campaigns flooded social media, fuelling polarisation and public scepticism about democratic institutions. This is not a uniquely Nigerian problem, but part of a global trend. A 2024 report from the Institute for Security + Technology warned that AI-powered disinformation campaigns are now a norm, with direct consequences for electoral integrity and citizen participation.

In the Sahel, AI is accelerating authoritarian consolidation. In Burkina Faso, deepfake videos have transformed Captain Ibrahim Traoré into a mythic figure, depicted as Africa’s messiah in digital campaigns featuring AI-generated music, starlike endorsements, and grandiose claims about infrastructure and social programs. In one wave of AI-generated content, a synthetic announcement by American Pan-Africans purportedly supporting the junta surfaced days after France withdrew its troops. In Mali, manipulated content on social media frames France and the UN as complicit in prolonging insecurity and exploiting the region’s resources. In Niger, AI-generated videos amplify pro-junta messaging and discredit calls for a return to civilian rule. These campaigns are often linked to Russian-influenced information networks. Generative AI is now a tool in the geopolitical competition over Africa’s political future, shaping public support for undemocratic regimes and destabilising regional governance.

Meanwhile, surveys confirm the danger is real as faith in democracy is declining across Africa. Afrobarometer reports that while roughly two-thirds of Africans still prefer democratic rule, support has fallen by seven percentage points in the last decade due to military coups and corruption. In 2025, the Mo Ibrahim Index noted that 78 per cent of Africans live in countries where governance and democratic participation have worsened, often due to repression of civic and media freedoms. This context makes AI-fuelled disinformation a force multiplier for democratic decay. It accelerates the spread of false narratives, erodes trust in legitimate institutions, and overwhelms citizens’ ability to discern truth from fabrication. By amplifying conspiracy theories, delegitimising elections, and glorifying authoritarian figures, AI-driven campaigns deepen cynicism and normalise undemocratic alternatives.

The dual-use nature of AI – capable of tampering with democracies yet also empowering authoritarian actors – underscores the urgency of crafting global governance frameworks. The responsibility is twofold for Nigeria: to safeguard its democracy at home and to champion norms abroad that ensure technology does not undermine Africa’s democratic future. In that regard, democracy in the age of AI requires more than defensive measures. It demands proactive investment in digital literacy, robust regulatory frameworks, and international cooperation. Here, Nigeria can lead by example. With more than 220 million citizens, half of them under the age of 19, Nigeria represents both the vulnerability and potential of the digital era. A youthful population that is globally connected but unevenly protected from digital manipulation is at once a risk factor and a resource for resilience.

This makes Nigeria the best-placed country to set the tone for an African-led response, and the country has already begun to act in tangible ways. The Federal Ministry of Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy has launched the development of a National AI Policy Framework to regulate the ethical use of emerging technologies in governance and electoral processes. On the sidelines of the 80th United Nations General Assembly in New York, Nigeria unveiled N-ATLAS, a pioneering AI language model trained in Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, and Nigerian-accented English. This is a bold signal that the country is staking its claim in shaping global AI technology in ways that reflect African voices and realities.

Fact-checking organisations such as Dubawa have deployed AI-powered tools to detect and debunk disinformation in real time, especially during election cycles. These domestic initiatives are reinforced by Nigeria’s multilateral engagement. The government is aligned with UNESCO to train its civil service on AI and digital governance, embedding global best practices into public institutions. Diplomatically, Nigeria has used its influence in ECOWAS and at the African Union to press for stronger regional standards on electoral integrity and emphasise African agency in multilateral forums. Taken together, these actions show that Nigeria is actively building the frameworks, tools, and alliances needed to protect democracy and set a model for the continent.

This is where Nigeria’s soft power can be most effective. Nigeria can spearhead a continental coalition on AI ethics, champion digital literacy campaigns targeting its massive youth population, and continue to press for African inclusion in global AI governance forums. Such initiatives would not only protect Nigeria’s democracy but also give Africa a voice in shaping the rules of a technology that will define the future of governance worldwide.

Leadership also means leading by example. Nigeria’s own electoral reforms, including the digitisation of voter registration and the expansion of civic education, must be accelerated to show that technology can strengthen democracy. Regulation should focus not only on punitive measures but also on supporting innovation that defends civic space, protects human rights, and enhances transparency. Such leadership would reinforce Nigeria’s credibility as a defender of democratic norms in a period where coups and authoritarian backsliding have threatened regional stability.

The age of AI will test democracies everywhere, but it also offers an opportunity to reimagine global cooperation. Nigeria has the size, the voice, and now the tools to lead Africa’s response. The choice is stark: allow external actors to script the future of its democracy or shape the rules of engagement for a digital century. Acting decisively now would turn Nigeria’s domestic vulnerabilities into diplomatic capital. That is the essence of soft power: projecting influence through culture or diplomacy, while embodying solutions that others seek to emulate.

The world is entering uncharted territory where the boundaries between truth and falsehood can be engineered with a few lines of code. Nigeria cannot afford to be a passive recipient of these forces. Our responsibility, and indeed our opportunity, is to help shape how democracy survives, adapts, and thrives in this new era.

LSE

For More News And Analysis About Mozambique Follow Africa-Press