Africa-Press – Namibia. SHELLEYGAN PETERSEN and CHARMAINE NGATJIHEUE NURSES from the Katutura Intermediate Hospital’s respiratory unit have had to deal with the worst amid the third wave of Covid-19 infections – including 12 deaths in one day.

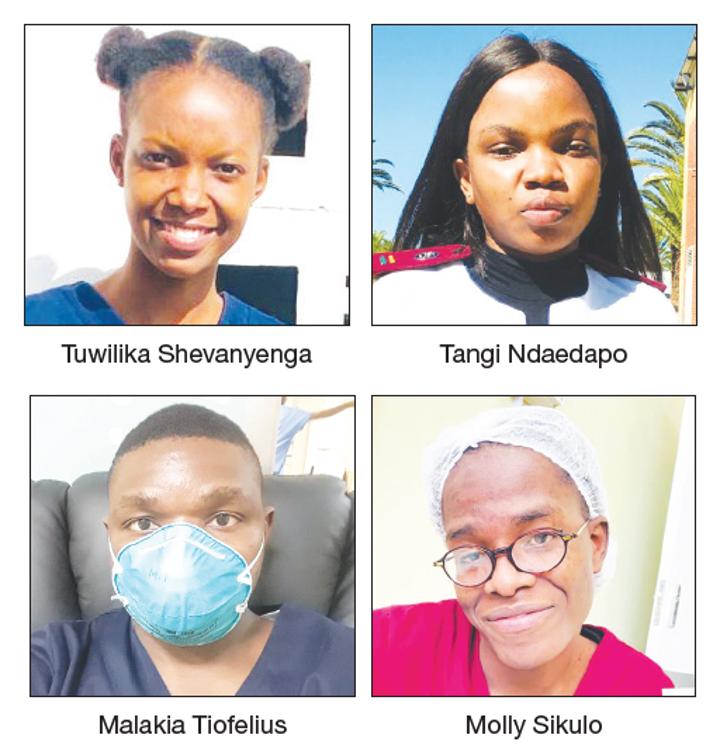

During this time nurses were expected to deal with more than eight Covid-19 patients at a time, because the respiratory unit exceeded its capacity of 74 patients. Molly Sikulo says at first it was hard. She has had to deal with patients constantly needing resuscitation, she says.

“You cannot break down in front of the patient, even if you really want to. So, you just try your best. You have to resuscitate two or three patients at once, and as a team you have to take turns to try and revive patients. It was really challenging – especially in May and June,” Sikulo says.

During these two months the country recorded 41 263 Covid-19 cases and 878 deaths, with Windhoek as virus epicentre, accounting for about 40% of cases at the time.

“Our bed capacity is 74, but we would end up admitting more than that. The private hospitals and the Robert Mugabe Clinic kept bringing patients here. We ended up with 80 patients. That time, you nursed up to seven patients [by yourself] who needed critical care,” she says.

Critical care nurses normally handle up to three patients per nurse, she says. Sikulo says one nurse would, however, at the height of the third wave, often be assigned two high-care rooms with 12 patients on ventilators.

“We were new when we came in, but later you learn to manage. We managed. The hospital would try to help us by sending interns here and there,” she says.

DESPERATE FOR MORE STAFF At the beginning of June, as hospitals were filling up, the Ministry of Health and Social Services advertised vacant posts at healthcare facilities.

The ministry needed to fill various positions – from medical officers to enrolled nurses. Posts in more than 10 job categories were advertised. Sikulo says she would lose up to seven patients in a 12-hour shift in June.

Among those she attended to was the late Gaob Afrikaner, who was a member of the Afrikaner Traditional Authority and the Nama Traditional Leaders Association.

“I nearly broke down that day [he died]. We tried our best … our best. I was so attached to the old man that when he left I felt all my energy drain out. I had to go into the room and calm down for a while,” she says.

FIGHTING INTERNAL BATTLES Tuwilika Shevangenga (23), another nurse in the unit, says years of studying and working at the hospital could not prepare her for the Covid-19 respiratory unit. Shevangenga, who graduated from nursing school this year, has been working at the unit since May.

“During my first month I was scared of this Covid thing. I was scared to get it, and I thought my life was at risk, but eventually I reassured myself that I chose this profession to help those who cannot help themselves,” she says.

She says during her training at the hospital she attended to stable patients, however, Covid-19 showed her how bad things could get. “On my third day at work, the wards were full to capacity, and there was an emergency. I was so overwhelmed. The first few days we observed. We had to resuscitate a patient. We were trying and trying …”

Shevengenga says she was fighting the daily internal battle between her fear of the virus and being strong for her patients. “Even though you are scared, you do not show them you are scared, because their lives are already on the line,” she says.

The registered nurse says every nurse was psychologically traumatised, and often had to take a moment to process their circumstances. Malakia Tiofelius (28), an experienced critical-care nurse, had to juggle caring for patients with training graduates.

“During the third wave of the pandemic, the mortality rate increased and it was really tough to cope. I had tasks to perform while I had to teach my colleagues, who were new at the time. They needed experienced nurses at the time, because some of the nurses had no experience in critical care, while others came straight from school,” Tiofelius says.

He says they hoped to nurse all their patients back to health despite the difficult conditions they worked in. At some point Tiofelius says he would be busy with a patient, while another nurse would need his assistance, forcing him to make a tough decision on who to help.

“For instance, a patient I’m busy with would have a cardiac arrest, while another patient is arresting there, which means now you have to weigh the options of who to attend to first. So it was really challenging,” he says.

When deciding which patient to attend to, he considered various factors, such as age and prognosis, he says. Tangi Ndaendapo (24), who embarked on her nursing career in June this year, says the experience has taught them a lot, although it was traumatising.

“At times it would be one nurse with eight patients, as opposed to having at most about three patients,” she says, adding that most of them were not prepared for how the pandemic panned out.

Ndaendapo says the group of graduate nurses has, however, grown attached to the hospital, their patients and each other. “It is bittersweet, but we developed relationships with our patients. We are glad the Covid-19 numbers are currently on the decline.”