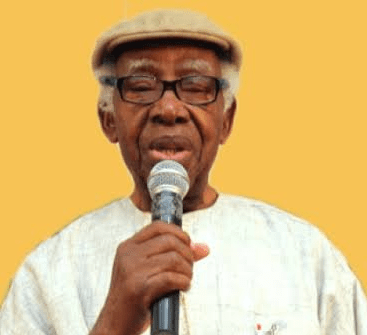

Exactly one month to his 98th birthday (April 24, 1921) legendary poet and one of Africa’s most renowned and established voices of the 20th century, Gabriel Imomotimi Okara, passed on , on Sunday 24 March 2019.

Gabriel Okara was educated at the prestigious Government College, Umuahia, in the 1930’s and 1940’s. According to Cyril Agbaku who wrote a tribute to him in Vanguard to commemorate his 96th birthday, Okara belonged to that “founding generation of African writers who had to be preoccupied much with the struggle for identity and ideology; and the concomitant battle of contrasting values in the colony (and post colony), to which Piano and Drums, perhaps more than any other poetic offering of his generation, appends an immortal signature.”

Although Okara’s literary footprints are global, he is a native of Bumoundi in Yenagoa Local Government Area of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. It was on that basis that the Bayelsa State Governor, Honourable Seriake Dickson, declared 3-day mourning for the late Okara, beginning from Monday to Wednesday this week with all flags to fly at half mast. The governor also described the death of the famous poet and novelist as a great loss to Bayelsa and Nigeria.

“Piano and Drums”

Why did Gabriel Okara, and not Christopher Okigbo, another great poet who was a pianist, write the great poem titled “Piano and Drums”? Interestingly, both Okara and Okigbo had attended the Government College Umuahia, though Okara was 11 years older than Okigbo. Another literary icon and contemporary, Chinua Achebe, had also attended the reputable Government College Umuahia. Okigbo had earned a reputation as a gifted pianist, accompanying Wole Soyinka in his first public appearance as a singer. It is believed that Okigbo also wrote original music at that time, though none of this has survived. Did Gabriel Okara draw his “Piano and Drums” inspiration from the piano-playing skills of his co-poet and contemporary, Christopher Okigbo? We may never know.

“Let us be happy,” continued Cyril in that tribute and interrogation of the piano and drums. “Let us roll out the drums – and, perhaps, the pianos too! I’m not aware if today, there is much by way of discrimination, as it was in earlier days, to compel a stringent definition of artistic preferences within exclusivist or exclusionist parameters: to declare categorically a preference for the drum as a mark of African cultural patriotism or the piano itself, which might mean a solidarity with an otherness that may not be entirely African. But at 96 (then), it is more than safe to say that Pa Okara has expectedly made the most, if not all, of the contribution a great writer of his stature would to world literature.

A classic by every standard, his 1950 poem, The Call of the River Nun, which won the ‘Best All-Round Entry In Poetry’ prize at the Nigeria Festival of Arts in 1953, remains an abiding watershed in the revolutionary depiction modern African writing brought to man’s inner (perhaps sometimes abstract) struggles in his journey between birth and death.

Some four years later, he would again blaze the trail for other writers by becoming the first Nigerian writer to publish in Ulli Beier’s interventionst journal, Black Orpheus (1957), eventually joining its editorial board shortly after. His collection of poems, The Fisherman’s Invocation (1978), won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize the year after it was published. The maturity of his lyrical vision, with an approach to language that remains deeply symbolic, while maintaining a rather swift succession of lines, flows into a stream of qualities that make his poetry gold standard in modernist scholarship anywhere in the world.

Around September 2010, the former Vanguard Arts Editor, great columnist, and now prominent academician, Obi Nwakanma, met Gabriel Okara at Canton, New York, where he read poetry with the great poet. Nwakanma’s impression of the legendary poet is quite revealing: “I had of course known Gabriel Okara first through his poems; we grew up on them. He was also that looming and legendary figure of letters, one of those Umuahians who came for homecoming and triggered possibilities in our young minds many years ago in boarding school at the Government College Umuahia. I had also met him occasionally thereafter, once at his old home on Rumuibekwe and another at his later home in Abuloma, Port-Harcourt. He remembered. And that is the wonder of it all: at 89 Gabriel Imomotimi Okara, poet of the delta not only had his mind intact, he was sprightly, in perfect health, and bouncy for his age.

“As we sat for a long, lingering breakfast, overlooking a golf course and a mild sun in descent, we went down memory lane, I prodding gently to retrieve the fragments of a remarkable life; a rich and textured life, and long. He (Okara) said, very humorously, over a generous spread of hash-brown, eggs and sausage, “you see, I eat slowly. I have to be careful now how I chew otherwise my teeth will fall all out. They are quite old now!

“Men like Gabriel Okara are the “living laboratories” of their age, to quote another remarkable member of his generation, Adegoke Adelabu. Okara was born in Nembe, by the River Nun. He attended the prestigious Government College Umuahia in 1935. Among his Umuahia classmates were the late Dr. B.U. Nzeribe of Awo-Omama, of the famous Nzeribe Hospital in Aba; Dr. Ijoma, one time Medical Director of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Umuahia; the famous Sports Administrator, Jerry Enyeazu; and Mr. Obuh, one-time Nigeria’s Postmaster-General. Most have gone on to immortality.

Gabriel Okara – taught to paint by Ben Enwonwu

“Ben Enwonwu taught me Fine Arts at Umuahia in 1937” Okara recalled. This is an important and hardly known aspect of Gabriel Okara’s life – that he is, before he was a poet, a talented painter, says Nwakanma. “His work was mostly in water colors. Most are lost. He, in fact, had a famous exhibition of his water colors in Lagos in the 1940s. Okara is a consummate artist; a man of the imagination. Among the quartet of Nigeria’s greatest poets of the 20th century his works speak to a passing time; a landscape on which is preserved, much like his lost paintings, a rich and magical world. He was Obiora Udechukwu’s boss in Biafra – there in Ogwa – where much poetry was made in the direst of situations, when suddenly the ack-ack of roaring guns from fighter planes would burst open the sky. The poet was visiting his son, Ebi, a clinical psychologist living with his family in another Canton, this in Massachusetts, and who has been resident in the United States since 1973 when he came to attend Vanderbilt University.

“The Call of the River Nun” a nostalgic poem about the landscape and river of Okara’s childhood; at that point a sort of absent force, it is an account of longing for the consolations of the familiar past and motion of the river, written atop the crags of the Milliken hills, when Gabriel Okara was living in Enugu. “Snow flakes Sail Gently by” is written from Okara’s first experience of snow in the winter of the windy city, Chicago, while he was on a year of academic fellowship at Northwestern; “One Night at Victoria Beach” is an acute observation of the religious and mystical life at Bar beach, Lagos, in the 1960s, and so on. Okara’s voice was strong;

Among his notable prose works are his first novel: The Voice (1964), as well as Little Snake and Little Frog (1992) and An Adventure to Juju Island (1991) which are children’s literature. Consistent with a long-standing literary passion, Pa Okara, after several years, returned with the collection The Dreamer, His Vision (2005): an instant success which became a joint winner, that same year, of Nigeria’s highest literary honour, The NLNG-endowed Nigeria Prize for Literature.

In 2009, he received an Honorary Membership Award from the Pan African Writers’ Association. These accolades notwithstanding, what appears to offer greater perspective to his oeuvre, in light of these times, should be the fact that Pa Okara’s writings constitute a body of foresight which, more than any other, accurately spoke to the epoch of globalisation in which the world is today immersed. Rightly, the world today has largely transcended geo-cultural boundaries. The body of literature denoting appreciation of -if we turn to it again- Piano and Drums, almost entirely misses the fact that the poem takes its relevance beyond the immediate moment of its birth.

The pattern has always been to depict a height of struggle between worlds European and African; the seething contrast between them and a predictable conclusion: if the one successfully displaces the other. But this body of stereotypes hardly embodies the true spirit of an offering whose title alone lays naked its intent from the doorpost, guiding, as it were, with the qualified assistance of a simple conjunction: and! Piano and Drums. Not Piano versus Drums or Piano against Drums. The poem speaks to a world in which contrasts co-exist as distinct but mutual entities increasingly interdependent; where junctions become conjunctions. A world in which Pianos and Drums find equal expression, both by symbolism and direction, with a guiding vision of commonality rather than opposition, distanciation and conflict.

The melody of both worlds, threshed in the interest of a common humanity, is the harmony of this new age. It is an age in which the world gravitates towards a centre: a centre that finds expression in virtual and extra-personal spaces. Hence, contemporary reading finds literary berthing that satisfies its collective quest for the interpretation of reality and location of meaning. And, Gabriel Okara, that deathless muse, more than 60 years ago, met the yearnings of ageless time. He is 96 years now – four years short of the centennial mark. May he reach it. May he exceed it. Long live the muse!

In a social media comment to a post announcing Okara’s death, one Dan Amor wrote: “Another master in the Republic of Letters departs. Daddy, please, tell Prof. Achebe, Prof. Ben Obumselu, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Profs. Emmanuel Obiechina, Adiele Afigbo, Donatus Nwoga, Sunday Anozie, Edith Ihekwuazu, Isidore Okpewho, Ezenwa Oheato, Catherine Acholonu, Zulu Sofola, Obi Egbuna, Nina Mba, Elechi Amadi, Cyprian Ekwensi, Buchi Emecheta, Femi Fatoba, Innocent Oparadike, etcetera, that Nigeria has gone totally comatose intellectually and culturally. May you all continue to rejoice in the literary firmament of heaven while we mourn and suffocate perpetually in this oven called Nigeria. Good night!”