Africa-Press – Rwanda. Dr. Fidel Rubagumya, an oncologist, is sometimes overwhelmed by the pain of his patients. Some are in severe pain and at late stages of cancer, with little chance of survival despite medication and treatment.

Others cannot access treatment because they cannot afford it, leading to cancer progression that could have been prevented if detected early.

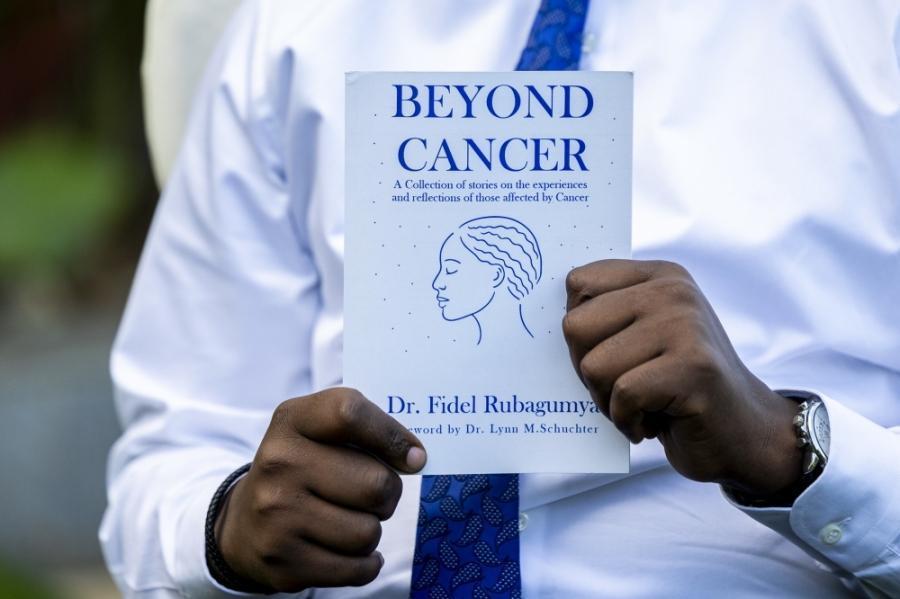

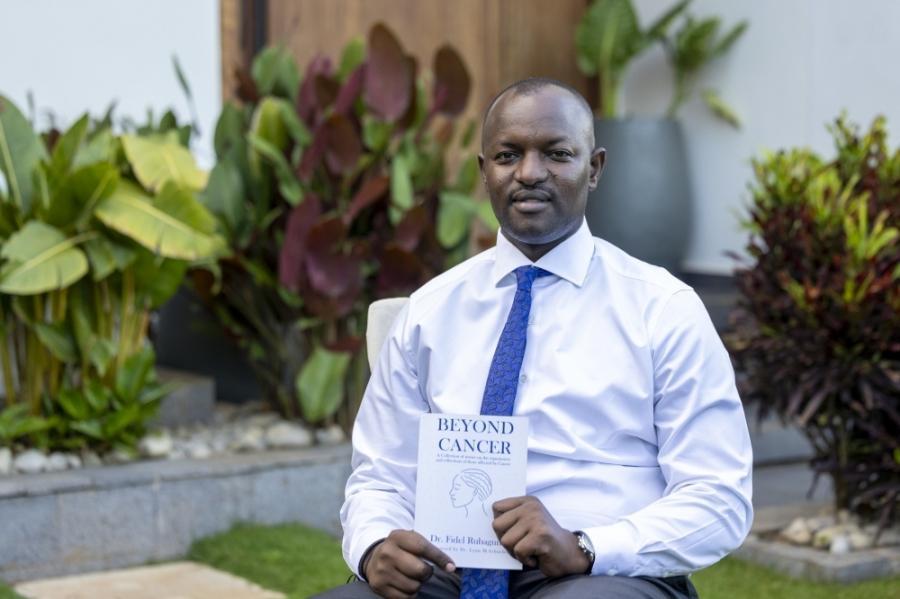

Dr. Fidel Rubagumya, an oncologist, wrote a book on cancer.

The expert noted that some days, after listening to patients describe their pain, fear, and uncertainty during consultations, he locks his office door at the Rwanda Cancer Centre inside Rwanda Military Referral and Teaching Hospital, breaks down in tears, and then composes himself, opens the door, and calls in the next patient.

It is a routine he said he never imagined he would carry. In his work, he deals with cancer cells, and carries the weight of patients’ lives including their losses, poverty, families torn apart, and dreams cut short. Over the years, those stories pile up.

Of the many experiences that caused him emotional strain, Dr. Rubagumya shared two. The first happened while he was still in training in Tanzania. He was a first-year oncology resident in Dar es Salaam when a man arrived from a remote part of the country with an advanced sarcoma—a rare cancer that starts in bones or soft tissues such as muscles, fat, or blood vessels.

The tumor had consumed nearly all of his face and scalp, leaving only a small part of his mouth visible. He had come alone, and during medical rounds, he could barely communicate, he said.

“At that time, we had very little to offer. The available chemotherapy was limited and not very effective. In other countries, he could have received treatment with better results. Here, our team tried several regimens, and none worked. He lived less than three months.

“The case showed me the limits of medicine in a low-resource place, and I started to wonder if this was a path I could really continue. I asked myself if this was the career I wanted to spend my life in,” Dr. Rubagumya said.

He noted that the second experience happened recently in Rwanda. A woman from the Western Province had completed radiation therapy after a month of sleeping on hospital floors due to lack of accommodation in Kigali.

“An NGO had tried to help her, but space was limited. She returned for a follow-up three months later, and when Dr. Rubagumya asked her to undergo imaging tests to check if the cancer had returned, she said she had only Rwf500 left, she couldn’t afford the tests.”

The oncologist explained that even with Community Based Health Insurance (Mutuelle de Santé) covering about 90 percent of costs, the remaining 10 percent can leave many patients without food for days. Some miss appointments because they cannot manage transport, lodging, or other basic needs.

Mental health support, opting for oncology

Dr. Rubagumya explained the emotional toll of oncology, noting that many physicians underestimate how extremely the work affects them.

Some shut down emotionally, some leave the profession, and others continue while quietly carrying the burden, he added.

“There is no structured mental health support for oncologists in Rwanda. Psychologists and psychiatrists are still few, and seeking help is mostly a personal choice. For me, getting through this work depends on loving what I do. I see every patient as if I am helping my mother. It is this approach that has kept me going,” the oncologist said.

Dr. Rubagumya lost his mother to cancer in 1998, when he was 11 years old. At the time, his family did not explain her illness. It was only in his fourth year of medical school that he discovered from hospital records that she had died of cancer.

Before that discovery, he had planned to become a surgeon, but learning the cause of his mother’s death changed his path, and he decided to train in oncology.

Dr. Rubagumya had chosen medicine early. In high school, all three of his university choices were medical studies. After completing six years at the University of Rwanda, he did his internship at Butaro Hospital and worked there as a medical officer before leaving for specialist training in Dar es Salaam.

He returned to Rwanda in 2019 as an oncologist and later sub-specialised in gastrointestinal cancers in Canada, completing nearly two years of fellowship supported by a scholarship from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

He is now a consultant oncologist at Rwanda Cancer Centre and a senior lecturer at the University of Rwanda. He also holds affiliations with international universities and contributes to research and training.

Dr. Rubagumya has launched his book on cancer, titled “Beyond Cancer”, where he shares stories, experiences, and reflections of those affected by the disease. He says his mother’s silence about her illness pushed him to write the book so that patients who cannot speak for themselves could be heard.

The book includes his sister’s account of living through their mother’s illness and testimonies from other cancer patients, highlighting both their struggles and courage.

“When parents hide their pain from their children, the impact does not disappear; it only surfaces later when the truth emerges. Families should allow loved ones to witness their journey through illness, so they can understand the disease and offer the support, care, and comfort that patients need,” he said.

The book took about a year to complete and is based on years of clinical experience and in-depth It is now available in bookstores in Kigali and online, with plans for an audiobook edition.

State of cancer, coming back home

Dr. Rubagumya said that while beliefs linking cancer and other chronic diseases to witchcraft have declined with expanded access to healthcare, some patients still seek medical treatment late after first consulting traditional healers.

He said most cancers are not hereditary but connected to lifestyle choices, including alcohol and tobacco use, poor diet, lack of physical activity, and random changes in cells.

The expert added that detection has improved, with more hospitals now offering advanced CT scans to detect tumors early.

“Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation are increasingly available at referral hospitals. Cancer medicines are being added to community-based health insurance, and he continues to train health workers in the country,” he stated.

When he returned from Canada, Rwanda had only three oncologists. Today, there are about 15 Rwandan oncologists, with more graduating soon through the country’s first oncology fellowship programme, which he helped establish. Seven trainees will finish this year, with another cohort already in training.

“I chose to return home, even though I had offers to stay abroad. I felt that someone from your own country, who speaks your language and understands your background, can make a difference. Coming back to share my expertise and contribute to healthcare here has given me a sense of fulfillment,” Rubagumya said.

He is married with three children and maintains a work-life balance. In the evenings, he takes walks, watches football and films, and spends time with his family. He said he learned to stop carrying patients’ stories home after realising the emotional toll it took on his wife.

Dr. Rubagumya said he will let his children choose their own careers. Whether they follow in his footsteps or not, he will guide them and create an environment where they can make their own decisions.

He plans to write another book focusing on oncologists and how they live with the weight of cancer care across Africa.

For More News And Analysis About Rwanda Follow Africa-Press