John R. Butera Mugabe

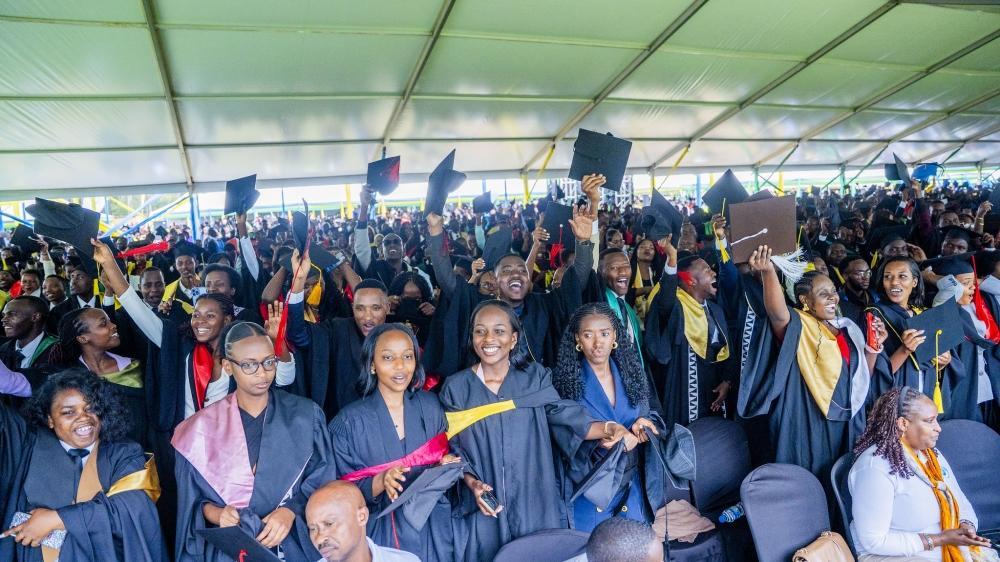

Africa-Press – Rwanda. JUST over a week ago, hundreds of students walked across the stage at the University of Rwanda to receive their degrees, a familiar ritual of triumph repeated each year in Kigali and at other universities across the country. Gowns fluttered, families cheered, and the national flag waved proudly over young faces radiant with promise. Yet beneath the celebration lingered a quieter, unsettling question: what, really, are these degrees worth?

Over the past few decades, Africa’s higher education sector has undergone dramatic expansion. Universities compete to enroll ever more students, new programmes open each semester, and graduation ceremonies have become national spectacles. Yet employers quietly confess a shared frustration: many graduates struggle to write clearly, think critically, or solve problems independently. Degrees, once emblems of intellectual discipline, too often serve now as mere tokens of attendance.

The paradox deepens when you look at the labour market. In some cases, a PhD holder applies for a position whose minimum requirement is a master’s degree, and still lists their kindergarten, nursery, and primary schools on the CV, as though education were a chronology rather than a measure of growth. It’s a telling sign of what’s gone wrong: we have confused accumulation with achievement, and certificates with competence.

The predicament does not lie only with the students. It begins much earlier, within the institutions themselves. Increasingly, university lecturers spend more time chasing consultancy contracts than preparing lectures. Their research is driven not by curiosity or the pursuit of truth, but by the incentives of business. They compete for donor-funded projects, NGO assignments, and private sector partnerships, while classroom teaching becomes an afterthought. The lecture halls fill, but knowledge transmission grows thin.

Even in the medical profession, once the embodiment of service and calling, the same trend is visible. Doctors compete not to perfect their practice but to match their peers’ income and business ventures. Clinics multiply; compassion diminishes. The professions once defined by purpose are now consumed by the marketplace.

We have entered an age where intellect and ethics are both being commodified.

Across Rwanda, universities are producing more graduates than ever, but fewer innovators. These have taught students to memorise, not to question; to pass, not to perform. When they step into the world of work, they are disoriented by its demand for agility, creativity, and accountability.

And then there is the matter of language, the most basic yet most revealing symptom of our challenge. Many graduates today master no language fully: not English, not French, not even their indigenous mother tongue- Kinyarwanda. Some people have argued that language fluency is not a measure of intelligence. While that may be true, the bare minimum of global competitiveness is the ability to articulate ideas clearly in a language that others understand. A thought that cannot be expressed is thought unrealized; learning that cannot be communicated is learning lost.

In many cases, the inability to express an idea, coherently, persuasively, and confidently, has become the quiet disqualifier of potential. In boardrooms, hospitals, and classrooms alike, miscommunication is the hidden tax on productivity. When a university graduate cannot write a paragraph without grammatical confusion or hold a conversation without hesitation, the degree loses meaning beyond the paper it’s printed on.

The problem is structural as much as it is cultural. We have prized expansion over excellence, mistaking access for achievement. Governments celebrate enrolment figures; universities chase tuition revenue; students chase credentials. But few pause to ask what those credentials mean.

In classrooms, questioning a lecturer remains an act of defiance; failure, a source of shame rather than an invitation to learn. Universities have taught obedience instead of originality, yet the 21st-century economy rewards exactly the opposite: adaptability, analysis, and innovation.

Rwanda, like many of its peers, recognises the urgency of human capital as the foundation of sustainable growth. Vision 2050 rests on the supposition that education will produce not just workers, but innovators and thinkers capable of driving transformation. To its credit, the government invested heavily in STEM, polytechnics, and partnerships with international universities. Coding academies, entrepreneurship programmes, and innovation hubs are rising across the country. These are promising signs, but the question remains: is the mindset changing too?

If education becomes a race for certificates rather than competence, the answer will be no. Reform must begin not with students but with the entire ecosystem, from how lecturers and teachers are evaluated, to how universities and schools define excellence. Teaching must be rewarded as much as research. Intellectual curiosity must become a virtue. Professors of knowledge must model integrity, not just publish papers or simply teach to pass.

There is also a moral dimension to this issue. When graduates leave universities unable to write a coherent minute report, express independent thought, or even communicate clearly, society loses faith in its institutions. The degree becomes an ornament, not a credential of competence. Employers begin to distrust education itself. Ambitious students, seeing this erosion, turn abroad, and the brain drain deepens.

The good news is that there is hope. In Rwanda, a quiet revolution in education is beginning to take root. Rwanda’s investments in applied learning hint at a different future, one where learning is not only about information, but transformation. But these reforms will matter only if they restore the sense of calling, the belief that teaching, medicine, and public service, are vocations, not markets.

A nation may construct highways, hospitals, and digital systems, the visible symbols of progress, yet without sharp, principled minds to sustain them, such achievements risk erosion. Rwanda knows this truth too well. The tragedy of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi was, in part, a failure of conscience and intellect. Had the country possessed enough enlightened minds, perhaps history would have taken a different turn. The next generation must not inherit progress it cannot preserve.

Education must become an act of empowerment, not entitlement. A degree should represent mastery, discipline, and the courage to think, not proof of attendance. The future will not belong to those who collect certificates but to those who can turn knowledge into leadership and ideas into positive change.

As I watched the graduates walk proudly, I felt both pride and apprehension. Their joy is deserved yet the challenge before them is huge. The world is moving faster than ever, and unless our universities and teachers rediscover their purpose, we risk producing generations fluent in credentials but silent in competence.

The caps have been tossed and the speeches delivered. But the real graduation begins far from the ceremony hall — in the marketplace of ideas and effort, where intellect, integrity, and expression are tested not by applause, but by the relentless demands of the world beyond university halls.

Source: The New Times

For More News And Analysis About Rwanda Follow Africa-Press