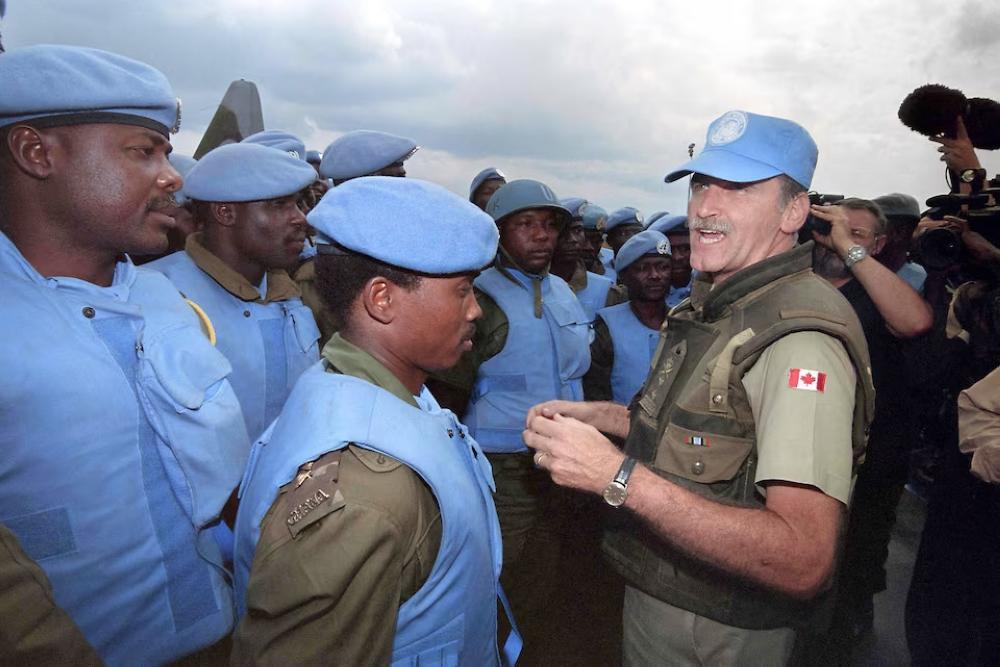

Africa-Press – Rwanda. On April 12, 1994, as the Genocide against the Tutsi raged, Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire, a Canadian military officer who was force commander of the UN peacekeeping mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), reported the killings, telling his bosses in New York about how he needed reinforcements.

However, what he got instead was calls from countries like Belgium for UNAMIR’s withdrawal instead of its reinforcement. During the genocide, Belgium withdrew its troops from UNAMIR. This, coupled with a diplomatic campaign for the total withdrawal of UNAMIR, effectively paralyzed the peacekeeping mission.

Belgian troops abandoned more than 2,000 Tutsi at ETO Kicukiro, who were subsequently slaughtered by government soldiers and Interahamwe militiamen.

In Bonn, Germany, Belgian foreign minister Willy Claes, told UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali that UNAMIR had become useless in Rwanda and was in danger. He added that there was an anti-Belgian climate in the country and proposed the suspension and withdrawal of the force.

Boutros-Ghali replied: “I share your analysis.”

Until then, the United Nations had consistently refused to strengthen the mandate of UNAMIR despite relentless appeals from Gen Dallaire.

Boutros Ghali was out of his office in the United States all the while, continuing his travels abroad despite alarming reports from UNAMIR reporting several deaths since April 7.

‘In Rwanda I shook hands with the devil’

In the preface of “Shake Hands with the Devil,” a book he wrote after the genocide, Dallaire summed up his Rwanda experience, writing, “I know there is a God because in Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him and I have touched him. I know the devil exists, and therefore I know there is a God.”

Dallaire wrote that he marked April 12 as the day the world moved from disinterest in Rwanda to the abandonment of Rwandans to their fate.

He wrote: “The swift evacuation of the foreign nationals was the signal for the genocidaires to move toward the apocalypse. That night I didn’t sleep at all for guilt.

“Kagame’s forces had ceased to squeeze and were now mounting an assault on Byumba. The major-general had given me twenty-four hours’ warning to get my forces out of the Byumba packet in the demilitarized zone. After I informed the DPKO [Department of Peacekeeping Operations] of the standoff in the zone and of my contingency plan for a possible withdrawal, New York sent us a little reminder that only the secretary-general could order a withdrawal – we had to stay until further orders. On the one hand, I was being told not to take unnecessary risks, and on the other I was being ordered not to take timely tactical decisions. At that point, I decided that I would take upon myself the decision to move my troops or not.”

As noted, Kagame’s chief of staff sent a formal response regarding Dallaire’s intention to stay in place in the demilitarized zone: “We have done everything possible to protect UNAMIR. Up to now, we have not shelled Byumba despite the shelling from the enemy. We have lived up to our commitment.”

Well, that was that, Dallaire wrote.

The battle escalated that day, he added.

‘Fresh horror stories’

“There were several exchanges of artillery and mortar fire, the fighting more intense and determined to the north and east of the city. A few bombs exploded around my headquarters and Luc’s Kigali Sector command, and a few of the thousands of civilians cowering at the Amahoro and the King Faisal Hospital sites were wounded. Reports from the UNM0s [UN military observers] still in-country carried fresh horror stories.”

In Gisenyi, present-day Rubavu, a tourist town on Lake Kivu, Dallaire wrote, an Austrian military observer reported a festive spirit on the part of the killers, who seemed oblivious to the sheer horror and pandemonium as they cut down men, women and children in the streets. In Kibungo, government soldiers were running a scorched earth policy against Tutsi and Hutu moderates.

In parts of Kigali, bulldozers had been brought in to dig deeper trenches at the roadblocks to reduce the piles of bodies.

“Prisoners in their pink jail uniforms were picking up corpses and throwing them into dump trucks to be hauled away. Think of that for a moment: there were so many dead that they had to be loaded into dump trucks. Whole sectors of the city were deserted except for wild dogs.”

Dallaire wrote that Kagame was bringing about three more battalions of troops into the north of Kigali and there was a lot of movement to the east of the demilitarized zone, toward Akagera National Park and the main north-south road along the Tanzanian border. Butare was tense because some Presidential Guards were in the area. Cyangugu, Kibuye and Gikongoro were scenes of ethnic killings by suspected CDR supporters and government soldiers.

“MILOB teams had established contact with an International Red Cross vehicle convoy of humanitarian aid coming from Burundi. The French had nearly completed their evacuation operation and were beginning to withdraw, with Luc’s troops taking up the French positions at the airport. France’s ambassador had closed the country’s embassy and flown out.”

Speaking on Radio Rwanda early on the morning of April 12, Froduald Karamira, one of the key leaders of the then ruling MRND party, told the country that “the war” was “everyone’s responsibility.”

He called upon the Hutu “not to fight among themselves” but rather to “assist the armed forces to finish their work.”

The same day, Radio Rwanda broadcast a press release from the Ministry of Defence that denied “lies” about divisions in the armed forces and insisted that soldiers, police, and all Rwandans had decided to fight their common enemy in unison.

Genocidal government left Kigali

The ministry asked Rwandans, soldiers and gendarmes to act together, carry out patrols and “fight the enemy.”

On the same day, the genocidal government left Kigali and settled in Gitarama (current Muhanga) where it continued to coordinate the extermination of the Tutsi in all prefectures.

Killings continued in various parts of the country. In the Nyawera and Mukarange sectors of Kayonza District, there were extremely cruel killings between April 11 and 12. At Mukarange Catholic Parish, the Tutsi who had taken refuge there were attacked by Interahamwe, police and the army, and were exterminated.

In the former Kibuye prefecture, on April 12, in the Rwamatamu commune’s administrative offices, a meeting was held from 10am to 1.20pm, attended by area residents and leaders. At the end of the meeting, the leaders reassured the Tutsi that peace had returned and that they should return to their homes. But not long after the meeting, a vehicle carrying soldiers and Interahamwe arrived at the commune, and shots began to be heard. More than 250 Tutsi were killed.

The same day saw large numbers of Tutsi from Kamonyi took refuge in the premises of Kigese health center. The killers attacked them and led them to Nyabarongo River where they were killed and their bodies dumped in the river.

The best-known site on Nyabarongo river where the Tutsi were rounded up before being thrown into this river is Ruramba. Such killings were always preceded by atrocious humiliations causing physical and mental degradation of the victims.

In Kigali, as killings continued, prisoners were used to load corpses of victims onto dumpsters before being taken and disposed of in trenches dug by tractors that had been meant to be used to construct bridges and roads by the Ministry of Public Works (MINITRAPE).

For More News And Analysis About Rwanda Follow Africa-Press