In the future, police and crime prevention units may begin to monitor the levels of pollution in their cities, and deploy resources to the areas where pollution is heaviest on a given day.

This may sound like the plot of a science fiction movie, but recent findings suggest that this may well be a worthwhile practice.

Why? Emerging studies show that air pollution is linked to impaired judgement, mental health problems, poorer performance in school and most worryingly perhaps, higher levels of crime.

These findings are all the more alarming, given that more than half of the world’s population now live in urban environments – and more of us are travelling in congested areas than ever before. Staggeringly, the World Health Organization says nine out of 10 of us frequently breathe in dangerous levels of polluted air. (Learn about how nanoparticles in the air could be adding to the harm.)

Air pollution kills an estimated seven million people per year. But could we soon add murder figures into this too?

t was in 2011 that Sefi Roth, a researcher at the London School of Economics was pondering the many effects of air pollution. He was well aware of the negative outcome on health, increased hospital admissions and also mortality. But maybe, he thought, there could be other adverse impacts on our lives.

To start with, he conducted a study looking at whether air pollution had an effect on cognitive performance.

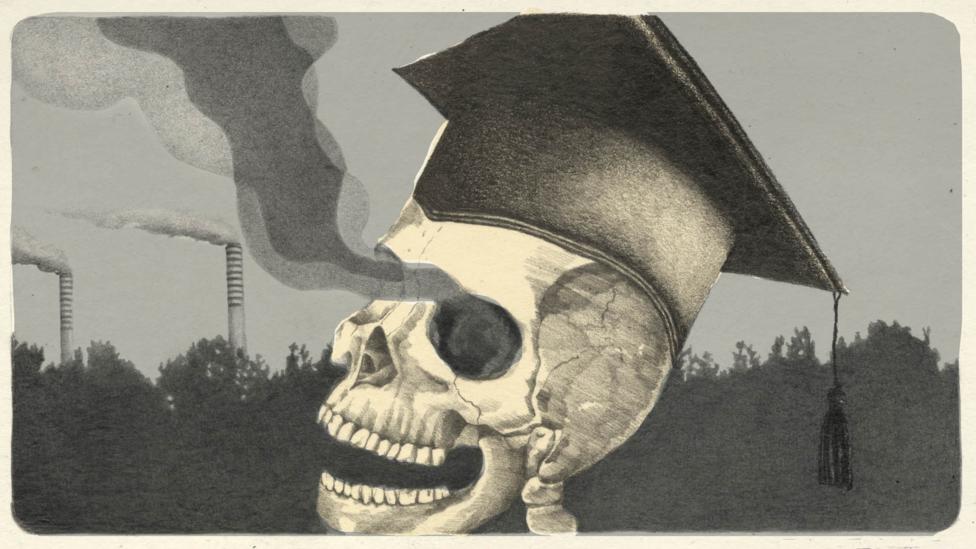

Roth and his team looked at students taking exams on different days – and also measured how much pollution was in the air on those given days. All other variables remained the same: The exams were taken by students of similar levels of education, in the same place, but over multiple days.

He found that the variation in average results were staggeringly different. The most polluted days correlated with the worst test scores. On days where the air quality was cleanest, students performed better.

“We could see a clear decline [of performance] on days that were more highly polluted,” says Roth. “Even a few days before and a few days after, we found no effect – it’s really just on the day of the exam that the test score decreased significantly.”

To determine the long-term effects, Roth followed up to see what impact this had eight to 10 years later. Those who performed worst on the most polluted days were more likely to end up in a lower-ranked university and were also earning less, because the exam in question was so important for future education. “So even if it’s a short-term effect of air pollution, if it occurs in a critical phase of life it really can have a long-term effect,” he says. In 2016 another study backed up Roth’s initial findings that pollution can result in reduced productivity.

These insights are what led to Roth’s most recent work. In 2018 research his team analysed two years of crime data from over 600 of London’s electoral wards, and found that more petty crimes occurred on the most polluted days, in both rich and poor areas.

Although we should be wary of drawing conclusions about correlations such as these, the authors have seen some evidence that there is a causal link.

As part of the same study, they compared very specific areas over time, as well as following levels of pollution over time. A cloud of polluted air, after all, can move around depending which direction the wind blows. This takes pollution to different parts of the city, at random, to both richer and poorer areas. “We just followed this cloud on a daily level and see what happened to crime in areas when the cloud arrives… We found that wherever it goes crime rate increases,” he explains.

Importantly, even moderate pollution made a difference. “We find that these large effects on crime are present at levels which are well below current regulatory standards.” In other words, levels that the US Environmental Protection Agency classifies as “good” were still strongly linked with higher crime rates.

While Roth’s data didn’t find a strong effect on the more serious crimes of murder and rape, another study from 2018 has shown a possible link. The research, led by Jackson Lu of MIT examined nine years of data and covering almost the entire US in over 9,000 cities. It found that “air pollution predicted six major categories of crime”, including manslaughter, rape, robbery, stealing cars theft and assault. The cities highest in pollution also had the highest crime rates. This was another correlational study, but it accounted for factors like population, employment levels, age and gender – and pollution was still the main predictor of increased crime levels.

Further evidence comes from a study of “delinquent behaviour” (including cheating, truancy, stealing, vandalism and substance use) in over 682 adolescents. Diana Younan, of the University of Southern California, and colleagues looked specifically at PM2.5 – tiny particles 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair – and considered the cumulative effect of exposure to these pollutants over a period of 12 years. Once again, the bad behaviour was significantly more likely in areas with greater pollution.

To check the link couldn’t simply be explained by socioeconomic status alone, Younan’s team also accounted for parental education, poverty, the quality of their neighbourhood, and many other factors, to isolate the effect of the microparticles compared to these other known influences on crime.